A Biological Experiment

by David H. Keller

A Biological Experiment (1928) follows a scientist's attempt to accelerate human evolution through selective breeding, raising unsettling questions about the ethics of genetic manipulation. "By the Seven Dooms of Man!"

"We have over fifty thousand babies with babies in the Government Nurseries, and we are asking for a four-year-old child. It will not be so hard on me then as it might be under different circumstances. Some women are even attempting to take care of a baby without help, but of course, they have never done any research work. I am willing to give as much as an hour a day to the child and will do all I can for its future health and happiness."

"You see it is this way, Leuson," said her husband. "You and Beth are very young and naturally you cannot see the responsibility of applying for a child — it is something you cannot comprehend as we do. My wife has been very wonderful about it and has promised me repeatedly that she would join me in an application for a child just as soon as she completed her investigations into the life history of the Cryptobranchus Alleghaniensis. This work, in two hundred and ten moving picture reels, is now completed; when it was shown to the International Society of Biologists, they made her a life member, an honor that has never before been given to any woman. It is true that she spent over twenty years at this work, but she has enjoyed every minute of it. She is just entering middle age and is well qualified in every way to supervise the care of a child. We are able to employ the best of help and can buy the most modern electrical equipment. We will welcome the child and give it every possible social and educational advantage.

"That is fine, Dr. Gowers," said the young man, enthusiastically. "If you were in my place, what would you advise me to do?"

The old Doctor smiled paternally, as he replied,

"Select an intelligent lady you can harmonize with and hand in your application for your papers and arrange for the preliminary treatment. You have a position under the Government and no doubt your wife could secure a place in the same office; then you can have a companionate marriage. I believe in early marriages and shall be glad to help you in any way I can. It may be that by the time you are thirty-five you can apply for a baby."

"I shall be glad to avail myself of your help," replied the young man. "Now we shall have to be going so we can have a long day's trip."

"Don't get tired, Elizabeth," advised the older sister. "You know you have passed all the examinations and the day for your operation has been set for next month. It is a great honor and I want you to be in the best physical condition."

Amid the roar of the engine, Elizabeth called back:

"Good-bye, Sis. When we come back you will see us."

They were off.

The two doctors walked back into the house. The wife said:

"I am in earnest about this new work of being a Mother. I am going to arrange a perfect program that will keep the three nurses busy."

"You will make a wonderful Mother," replied her husband, with a far-away look in his sad eyes.

Rising rapidly into the air, the monoplane made certain circular movements and then started westward along the Potomac. Although the machine was capable of three hundred miles an hour, Leuson seemed satisfied with a much slower pace, and they did not reach Pittsburg till late in the afternoon. At that time there were less than ten thousand people in that city for there was but little demand for coal or steel in the new age of atmospheric electricity and glass. Leaving the plane on the aviation field, the young people walked to the office of the local Judge. This official had been in office for so long that he had become careless of details and obsessed with the idea that he could not make a mistake. For this reason he did not thoroughly examine the papers Leuson handed him, but asked gruffly:

"So you want to enter into a companionate marriage?"

"Yes, sir," was the double reply.

"Are you able to support yourselves individually?"

"Yes, sir."

"You have your permits, vaccination certificates, life insurance, health, accident, tornado, air and happiness insurance?"

"Yes, sir."

"You each consent to an immediate and complete divorce in case you are ever unhappy living together?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then I pronounce you man and wife. Sign these papers so I can send them to the Central Matrimonial Office. Is this your first experiment?"

"Yes, sir."

"I was married eleven times before I could find a woman I could live with. I understand that is not an unusual experience."

The young people rushed from the office, and walked back to their plane. Leuson looked a little worried, as he said,

"I am sorry that I had to forge some of those papers, but let's go."

The monoplane, avoiding the usual air lanes, went steadily westward, finally resting on the grass of an isolated meadow among the peaks of the Ozark Mountains. There was sunshine here and a little singing brook and while three sides of the meadow were sheltered by dense woods, the other side was guarded by a sheer cliff of overhanging rock, which rose some hundreds of feet above the cleared field. The young people acted as though they were thoroughly at home. As a matter of fact, they had made frequent visits to this field and had thoroughly prepared, as far as they could, to make this place their home.

Traveling all day and night, they had reached the meadow just as the sun was first kissing the tree tops. They were tired, but they were far too excited to rest, so they started at once to unload the plane and carry their packages up a narrow, winding mountain path which the boy had constructed, and which ended in a cave one hundred feet above the level of the field. After everything had been carried, the plane was put under the trees and covered with waterproof canvas. They never intended to use it again, but they felt that it might be useful in an unexpected emergency. Finally the necessary things were all done and the boy and girl, for they were little more, sat down to rest on the narrow rock shelf in front of the doorway of their new home. They dissolved a few synthetic food tablets in a pint of spring water and slowly sipped their meal.

They put a few pillows behind them and sat there looking toward the west. The girl shivered but it was from cold rather than from fear.

"Now, tell me, dear, just what you have really found out about it all."

He drew her closer to him as he started to talk.

"Of course we are just youngsters, Elizabeth, but I guess we are old enough to know our minds, and decide what we want. I have been reading a lot of the history of the thing and I was just fortunate enough to be able to find some real old books and take them out of the Congressional Library.

"Years ago, when we first found each other and realized that we were in love and wanted to be different from other folks, we knew that unless we learned to read we should have to receive the same mass education that all the young people received. Even then we were tired of looking at the educational moving pictures and listening to the same lectures given over the radio. It was this that prompted us to seek positions where we could learn to read and have access to the old books. Do you remember how we used to talk about it? How in those back rooms in the Library were printed books that no one had read for centuries and yet which were carefully guarded under lock and bolt so no one would get them?

"It seems odd, but we found that it was a fact that the citizens of a supposedly free country have had no choice in their education or amusements for over a thousand years. Every home has its radio, its movie, its televisional box; but every fact and picture that came to them was approved of and censored by the National Board of Education and Amusement. No one had a right to have a private opinion; everyone had to think like everyone else. There was a gradual death of individuality. Whenever a change was desired in mass opinion or action, an educational propaganda was started. Finally, all thinkers were engaged by the central government. If they wanted to make any statement to the world, they had to have their message passed by this National Board. The entire learning of past ages, put into books, was a closed secret, save to a few who were taught to read, that the art might not be entirely lost.

"As you know, we both were fortunate enough to secure this special education. Then finally my chance came and I was selected as the night watchman. After months of search, I located the books I wanted — and stole them and stole you. Now I want to tell you the history of this problem.

"This is June, 3928. A great many centuries ago life was very different in this world. Everything has changed during the last twenty centuries. But I want especially to talk about love, marriage and babies, and to give you some idea of the changes in these three important divisions of the human economy.

"Twenty centuries ago there were lots of babies and they were all born. That is just a four letter word that means nothing at all to you now, but at that time it was the only way whereby the existence of the human race could be maintained. A man and a woman married each other and in the course of time a baby was born to them. Strange as it may seem to us now, the baby was the actual child of the two persons who called themselves its Father and Mother. These babies all reached the breathing stage of existence at the same age, they all looked alike, they all had the same average intelligence and it took a lot of care and love to raise them — also a lot of intelligence — and as a consequence, a great many of the little things died the first year. What I want you to understand is the fact that any two persons who were married had a right to have one child or a dozen. The license to marry automatically carried with it the right to have as many children as they wanted to. This was centuries before the National Child Permit Act was passed.

"There were so many babies in so many families in those days that it was quite a problem to raise them. The amount of detail and care each baby required must have been terrific. If a child was intelligently looked after twenty centuries ago, it took fully six hours a day of the Mother's time. At least so I have read in the old records. The condition is nicely illustrated in the old patents applied for at that time. Some are hard to understand but all seem to have for their object the lessening of the time that had to be daily spent on each baby. Life for parents in those days must have been one continual round of duty.

"Yes, I am satisfied that there must have been a lot of trouble twenty centuries ago with babies, having them the way they did and having to care for them. Then, too, there was such a scatter of the babies. Some families had a dozen and some had none or perhaps just one. Many of the babies were not well; they had a lot of diseases that we have not seen for over fifteen hundred years and some doctors were able to make a living just treating sick children. The sad part about it all was the fact that those who were wealthy and intelligent seemed to have the fewest children. It was only the poor and ignorant who had large families.

"Just about two thousand years ago a Judge, in what was then the United States, wrote a book about companionate marriage. I translated this into modern English and waded through it with a great deal of interest. Of course it is very far behind the times but we shall have to give the Judge credit for starting something. He had a law passed which allowed a man and woman to marry each other and live together as long as it was mutually agreeable to both of them. They were not supposed to have any babies born to them until they were fairly sure that they would want to live together for life.

"One hundred years later a law was passed to the effect that no woman was to have a child until she and her husband secured a permit from the Baby Board, and it was thought that this would diminish the number of babies in poor families. All children were supposed to be born in government hospitals, and a woman was not admitted without her baby permit. Naturally, lots of babies were born surreptitiously without permits. It all worked out very unsatisfactorily.

"By the twenty-seventh century the human race was in a rather pitiful condition. All of the so-called savage races had been blotted out of existence by new and deadly diseases. The Caucasian race saved themselves after a death rate of fifty percent. Those who remained alive were almost degenerates in many ways. The extensive use of the automobile came near withering the legs of the genus Homo. The only perfect form of man or woman was of marble in the art galleries. The hospitals for the insane and feeble-minded and epileptic were crowded to their utmost capacity. As a final resort Congress passed a National Sterilization Act, affecting those who should be found unfit to have children.

"For a while it worked and then it was discovered that so many people were being sterilized because they were unfit to be parents, that the human race was rapidly shrinking in number. Sterilization solved so many of the problems of modern life that it became too popular — almost a fashionable fad. When a man and woman entered into a companionate marriage they thought they would feel a lot happier if they knew they would never have babies. This condition of affairs existed in and around 2800. The people actually abused the law and took advantage of the National Sterilization Board. You see, before a person could receive a sterilization permit the Board had to be convinced that the applicant was mentally and physically incompetent to have children; and many bright, intelligent men and women would go before the Board and take the examination and pretend to be feeble-minded just so they could receive the permit. Those were the very people who should have had the babies; yet they were the ones who did not want them. Having a baby in those dark ages was almost as bad as death itself.

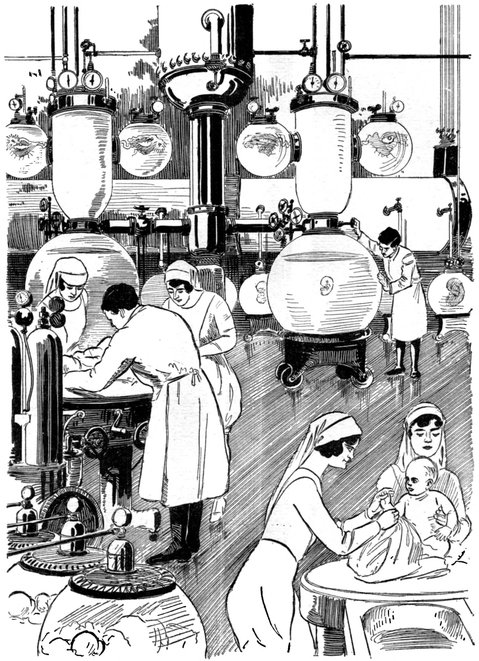

"The human race at that time was not only degenerating as individuals but disappearing as a species. It was at that time that our scientists began to talk about synthetic babies. A lot of research and experiments were done on the lower forms of life. It was found that a piece of heart muscle from a chicken embryo could be kept alive indefinitely and go on growing in an incubator. Later on the surgeons were able to keep entire organs like the liver and spleen alive, and transplant them into the site of similar diseased organs. It was determined that the eggs of the sea urchin would grow into mature adults without the aid of the male; all that was necessary was to put them in water containing certain salts at a certain temperature.

"These experiments finally ended in the discovery that the human ovary could be kept alive and functioning under certain conditions in a glass vessel. Such an ovary was able to develop and expel a perfect ovum every twenty-eight days. By a process similar to that used with the eggs of the sea urchin, these ova could not only be kept alive but could be developed into fully matured babies. At a certain point in their growth, they were taken out of the sterile glucose solution and respiration started with a pulmometer. As far as any tests were concerned, they were just like all the other babies.

"A great many of these synthetic babies were made and allowed to grow up under ideal conditions. It was soon discovered that they could be kept free from all the diseases of childhood, they could grow into vigorous adults and be compared very favorably with the best of the race — provided they came from the ovary of a woman who was perfectly normal. That caused a lot of thinking and the thinking ended in the rapid collection of material and building of large numbers of special laboratories to grow these synthetic babies in.

"When all was ready, the Universal Sterilization Law was passed. All young people were required to spend a few minutes under a special form of radium ray when they reached a certain age and no one was allowed to enter into a companionate marriage until this had been done. The continued supply of material for future use was provided for by one of the sections of this act which stated that all young women were to take an examination and those who were nearly perfect in every way were required to submit to an Oophorectomy and were compensated for this by special pensions and privileges denied other women. In regard to this, I need not remind you that it was one of our reasons for fleeing from modern civilization. It was a danger that threatened you in all its horror.

"Anyway, the machinery was finally set into motion. The records show that the last child was born on the western continent on July 4th, 3009. Since then the race has been kept alive by the production of synthetic babies. About one hundred and fifty thousand babies are produced every year. They are all perfect in every way because any who show defects are not allowed to develop. The Government keeps them in nurseries till they are called for. We saw how that happened in the case of your sister and brother-in-law. After they were forty years old, they decided to apply for a permit to take a baby and they asked for a four-year-old child.

"These babies, grown under ideal conditions, the offspring of tested ovaries, have in a thousand years saved our race from degeneration. In fact, everybody now is perfect in practically every way. There is little sickness and people finally die painlessly of old age. Of course we have not a very large population, but what we have is composed of very fine individuals."

At this point Elizabeth Sellers jumped to her feet as she exclaimed,

"And yet in spite of the perfectness no one is happy!"

"That is it exactly!" agreed the young man. "There has been no trouble in making a living, everybody is comfortably housed and clothed, there is no sickness, food is abundant, everybody is working at some interesting work — and yet no one is happy! We saw that years ago and we know now that it is true."

The young woman sat down again and snuggled close to the man.

"Tell me again why they are not happy. I have heard you tell it before but tell me again. I want to hear it out here in the wilderness where we are alone — together."

The man put his arm around her and drew her close to him as he replied, and his voice had the soft tenderness of a breeze in the spring time, as it scatters pollen.

"They are not happy because love has disappeared from the world. When children grow up now, they have only permit parents. They think they are falling in love when they enter into a companionate marriage. All they do is to share the same house during the hours they are not working. After they have accomplished all their ambitions require of them they try to satisfy their desires for a family by securing a baby permit and a child. The child can be of any age when it is taken into their home. It is a child from the ovary of a woman who may have been dead three hundred years. It is a child that never had a father. The man and woman pretend that it is their child but all the time they know that it is not so and so does the child. The four-year-old baby your relatives are adopting this week can think and talk. Can it believe that this man and woman love it when they let it stay in a government nursery for four years without claiming it?

"There has been a surplus of women. These have been used as nurses. Your sister will do nothing for her child except supervise its care by three experienced women who know a thousand times more about child culture than she does. The child will grow up to be intelligent, strong and beautiful, but it will grow up in an atmosphere devoid of love. A man and woman who are married, the way they are, in this period of civilization, do not know how to love a child because they never loved each other."

"But what is love, anyway?" asked the young woman.

"Love is sacrifice!" was the reply. "That seems to be the only definition. I have read the old books and when people in those old days were in love they always had to sacrifice themselves. A boy and a girl in love with each other waited for years till the time came when they could marry. They gave up their ambitions, their future, their success in life so they could marry. For years most of them felt, what was called in those days, 'the pinch of poverty.' There was sickness and constant work and struggle for the necessities of life. The love life centered around the house they lived in and they called this house a home. This is a word that disappeared from the English language years ago, centuries ago, when it was destroyed by the automobile, the aeroplane and moving picture, to say nothing of the companionate marriage.

"They lived in a house that they called a home and they had children. Every child they had made life harder for them. Knowing nothing about it they had to learn to raise babies and care for them. The little things were often sick. The father worked all day and helped care for the children at night and the mothers never ceased to work. The children died and the men had to borrow money to bury them. That was before the time of universal Government cremation. Often the wives died and left the men with children, with little babies one day old; or the husbands died and left the wife to struggle on till the children grew old enough to help. Everything in that life meant sacrifice and out of that sacrifice grew the thing the old poets called love. It was so very different from what we call love today."

"You know so much about the old love," whispered the girl.

"That is because I have read of it. At its best it was a beautiful emotion and at its worst it was worthwhile. It made existence human. They lived like animals but they worshipped each other as though they were Gods. They were hungry and destitute and poor and sick and weary but when they faced the sunset of life together, they were happy — because they had sacrificed everything and as a result of this sacrifice they had found love. Their house was often poorly furnished and the place of much hardship but it was a home. Their babies were sick, cross and a constant care, but they were their own flesh and blood. When a man wrote about love in those days you knew he was happy in spite of everything.

"It is hard for a young man like me to tell whether all that has happened is for the betterment of mankind. We are taught by the Educators, that at the present time we are in a Golden Age. The factors that made life hard for the human race twenty centuries ago have all been disposed of. We no longer have disease, hunger, poverty or crime. All we know about such hardships is obtained from our ancient histories. Every detail of our life is provided for so that we can obtain the maximum amount of satisfaction for a minimum amount of effort. Nothing has been neglected.

"Yet you and I have fled from it all. Why? Simply because we wanted something that modern civilization refused to grant us. For some reason we became, even as children, atavistic. We wanted to live like the savages of twenty centuries ago. We wanted to toss aside every invention that had made life a luxuriant certainty and take our chance with the animals and the birds. Scorning a house with electrical appliances of all kinds, with radio, television, monoplanes, synthetic food, central heat and daily amusements of every kind furnished by the Central Board of Education and Amusement, we have determined to make out of this cave a home. We know there is water down in the brook; there is such a thing as fire and all around us is wood in the shape of trees. Somewhere near us there must be food of the kind our ancestors ate, meat and vegetables. If that fails, we have enough synthetic food to last us a year, but just as soon as we can, we must change our diet. These books I brought with us tell how to cook with fire. We shall have to make some furniture and somehow make receptacles of some kind to cook in. Every day we will be doing a dozen things that no man or woman has done for a thousand, fifteen hundred years. No doubt we shall do them rather poorly and clumsily at first. Still we have brains and books to instruct us in these ancient arts and we shall at least be able to keep busy. We shall have to keep busy to prepare for the cold weather."

"It will be a lot of fun," said Elizabeth, though her tone did not indicate anything but the most serious mood. "It will be real sport to work out all these problems and learn to do all these new things that were so usual and commonplace centuries ago. It thrills me to know that I will soon be doing things that no woman has done for so many hundreds of years. Over eight hundred years ago it was found that synthetic meat could be made so easily that it did not pay to keep animals for food supply any longer, so they were all turned loose. Their ancestors were carefully housed and fed to give mankind meat, milk, shoes and clothes and now their descendants in large herds roam over the deserted farm lands. I am glad that we came. It is good to know that our vision has turned into a reality. I know that I shall never be sorry."

They talked on and on till the moon came up and finally they talked themselves to sleep out on the rock and did not realize what had happened to them till they awoke the next morning, rather stiff and sore from their cramped position and hard stone couch, but very happy in the fact that they had each other and that the cave was to become a home and that they felt an emotion which they knew was the old kind of love.

The Librarian of the Congressional Library received the report that certain books had been stolen from the shelves. He was also notified of the fact that the assistant watchman had disappeared. Going to the card index of individualities, he was not at all surprised to find that Elizabeth Sellers, No. 237,841, had disappeared at the same time. He took her card out of the files, also the card of the watchman, Leuson Hubler, No. 230,900. After that he spent some hours of careful thought going over the pages of a small book in which he had kept some very personal records in pen and ink, something that at most only a dozen living men were able to do, for the art of penmanship had disappeared with the invention of the psychophone, an instrument that directly transferred and preserved the thoughts of a person, so that at any time in the future the small glass cylinder could be inserted into a radio and repeat the thought. This machine had completely supplanted the pen and the typewriter in the commercial, literary and educational life. Only a few of the savants were able to write, so the Librarian was more than safe in using that method to preserve his observations concerning No. 237,841 and No. 230,900.

After a week had passed he went out to call on Dr. Gowers and his wife. He was nearly thirty years older than they, but had seen a great deal of them socially, and admired them very much, especially for their ability to follow a certain line of investigation to its ultimate ending. In fact, he often stated that when these two were finished with the study of any problem, there was nothing more to do on the subject.

He found a charming family group out on the well kept lawn. There were the Doctor and his wife and three matronly ladies who wore the uniform of trained nurses, and they were all paying the greatest attention to a little girl who was playing with a rubber ball. Dr. Gowers welcomed him cordially,

"I am so glad you have come," he said. "I want you to see our little girl, Lilith. We have just taken her out on a permit and I am sure you will agree with me that she is far above the average for a four year old child. Having her with us has made the disappearance of Elizabeth easier to bear."

"Is Elizabeth gone?" asked the Librarian, in pretended surprise.

"She certainly has!" replied Dr. Helen Gowers. "She and a boy that was working in your library went up in the air a week ago for a ride over and they never came back."

"Is that so? Perhaps they had an accident."

"No, indeed. You know as well as I do that the last accident to a plane happened over five hundred years ago. No! They did not come back, for the reason that they wanted to stay away. Elizabeth took a lot of her clothes and jewels with her. They were married in Pittsburg on forged permits."

"Why I never heard of such a thing!" exclaimed the Librarian.

"Neither has anyone else. Such a thing has not happened for over a thousand years. I had a hard time before I was even able to find out what such a thing was called. Its name was Elopement. It has been so easy for young people to enter into a companionate marriage and everybody is so glad to help and encourage them to marry, that anything like this just never was thought possible."

"I confess that I cannot understand it," interrupted Dr. Gowers. "We have tried to be like parents to Elizabeth and I am sure that if she and Leuson had only come to us, we should have been glad to listen to them and help them apply for their preliminary treatment and marriage license. Of course, things might have been delayed for a few months by Elizabeth's operation, but her pension from that would have made it very easy for them to live the rest of their lives."

"Looks like the action of some lower animal," said the Librarian.

"That's just what makes us feel so bad," said the wife. "They just went off like two animals. I only hope that they will come to their senses and return for a pardon, which I am sure will be granted. Perhaps they will have a logical explanation for their conduct. Have you time to come into the house? I want you to listen to the daily programme I have arranged for these three nurses who are going to care for Lilith under my supervision. I have filled twelve psychophonic cylinders with my orders and I believe that it can serve as a perfect example of correct child culture. It may be good enough to use in the National Educational Department."

"Of course," added the proud husband and father, "you understand that this is our first child and we have only had her for four days. Helen is so capable and enthusiastic and confident about her ability, that she feels she has already added to the knowledge of the world by preparing this programme."

"I am sure," said the Librarian suavely, "that she will make a perfect mother, and just as soon as I can, I will drop in for the evening and listen to the twelve records. Just now I shall have to fly back to the Library. I am very sorry about your sister. If you hear anything of her, be sure to let me know."

However he did not go back to the Library; instead he went to see the Head of the Biological Maternity Units. The two men had been fast friends for many years. He spent several hours in conference, and when he finally returned to his office, he tingled with a strange enthusiasm such as he had not experienced for many years.

After that there was nothing for him to do but wait, which he did with a very definite impatience.

It was late autumn; to be exact, it was the last day of November. The Librarian, who lived amid his treasures, was listening to a psychophonic lecture on the latest evidence of life on the planet Venus: at least he was pretending to listen, but most of the time he was asleep. He suddenly was aroused to find that there was a man seated in a chair, near him. He looked at him a moment and then jumped to his feet,

"By the Seven Sacred Caterpillars! If it isn't Leuson Hubler! My dear boy, where did you come from and where have you been?"

The young man smiled as he replied,

"Did our disappearance cause much of a sensation?"

"Not much. The Gowers were so powerful that they kept it out of the daily-radio-news-transmission-service. Elizabeth's sister feels the disgrace keenly."

"I believe that. Well, we are safe and so far are having a wonderful time, but I just had to have some things that I could not make and I knew they were in your museum, so, considering you are to blame for it all, I made up my mind to come and ask you for them. I want an ax and a saw and a hatchet, several iron kettles, a frying pan, a rifle, some ammunition and — oh — a lot of things that we shall need to get through the winter on."

"I hardly know what you are talking about," said the Librarian, "but if you know what you want and can recognize them, I will give you everything. But where in the world are you living?"

"We are living in a cave."

"Like a pair of toads?"

"No! Like Gods! We are savages, Father, if you know what that means. We went back to the age of the Troglodytes. You are to blame for it all. You had me taught how to read and gave me a position where all the old books were available. You even picked out love stories of the ancient times and urged me to study them. It was you who first introduced me to the novels of Henry Cecil, such as The Adorable Fool, Wanderers in Spain, and The Passionate Lover. You urged me to dust and read Prue and I and Reveries of a Bachelor, and in the field of poetry you advised Idyls of the King and Songs of a Spanish Lover. I read those books when a boy and they made me different. And when I met Elizabeth Sellers, I met a girl who was willing to listen to something different and this is the result; so if it has been a sin and a crime to do what we have done, you are to blame."

The old Librarian smiled,

"Everything you say is true but it is only part of the truth. It has all been a wonderful experiment but the details had to be kept from both of you; otherwise you would not have been free agents; but before I tell you about it, let me assure you that I, at least, do not think that you have done anything wrong. Now this is what happened.

"About thirty-six years ago I had a daughter, and the same year my friend, the Head of the Biological Maternity Units, also took a little baby from the Nurseries. The two girls were of the same age and almost grew up together, as we were living next door to each other. We thought it would be a fine thing to give them a liberal education and so, by the time they reached fifteen years of age, they knew a great deal and more than was good for them. They were beautiful women, and they had some very beautiful and impracticable ideas. They were both in love with two nice young men who, unfortunately, were also more or less dreamers.

"At the time of the yearly examination of the young women to select material for additional ovamaters to supply synthetic babies, these two young women passed a wonderful examination and were ordered to the operating room. They would have been pensioned so liberally that they could have married and lived comfortably the rest of their lives. What really happened was that they both committed suicide the night before the operation. You may not be familiar with that word, so I will tell you that it means to kill oneself. We were all so shocked by it — it was so unusual, that we kept the matter quiet; but it made a deep impression on my friend and myself. We talked the tragedy over and hastily decided to make what amends we could. Secretly, my friend operated on their bodies before we sent them to the National Crematory, and then he started to grow their children. It was my idea that he should continue with this work till he produced two children, a boy and a girl, and then destroy the two ovamaters. This was done, and as soon as I could do so, I applied for a baby and selected you. In order to avoid suspicion, we arranged to have the girl placed with the Sellers family. They had one daughter and wanted another. Unfortunately the parents died before the little girl was mature and part of her care was assumed by her sister, who was married to Dr. Gowers. But the sister was so busy with her experiments that she did not have much time to spend on the little one and she just ran wild, most of the time with you. The escapades of you two children nearly drove us all insane — for example, the time you broke the time record for a non-stop flight around the world, following the equator. Still, thanks to my early training, you wanted to be with books more than anything else, and Elizabeth was always willing to hear you talk and believed all you told her. You seemed rather slow, so I had Elizabeth put on the list for operation. That caused the explosion. My dear old friend, who is a sort of a grandfather to Elizabeth, is as pleased as can be about it all. He feels that it is a wonderful atonement to two dead women and a splendid and unique experiment in biology. Without your knowing it, we gave you a chance to be happy. It is no wonder you say that you have been living like Gods."

"So you two planned it all?" asked the astonished young man.

"Just about. Of course we did not know how you two would work out the details. We knew that you would have to get beyond the reach of the Government to even start. If the authorities found out where you were and what you had done, you would probably be placed in solitary confinement for life, though that is a punishment that has not been necessary for a thousand years. In this case, however, they would feel that it was imperative. Suppose your conduct became known? What if the young people adopted it as the latest fad? You can readily see that the entire economy of the human race would be disrupted. Of course you can depend on two old men to keep your secret, but as far as the world is concerned, you had better consider yourself dead, for you must not come back."

"We do not want to come back, but I cannot see what harm it would do!"

"Just this. It would disrupt our present civilization. Suppose that Elizabeth has a child. The last birth occurred in 3009. But before that, for hundreds of thousands of years every child was born with a mother. The desire to give birth to a child was as much a part of their lives as the desire to eat and sleep. For nearly a thousand years, all women have been sterile and have had to be content with synthetic babies, but do you suppose that the desire to have babies of their own has disappeared from their mind and soul? No, indeed! It is still there and it is a powerful desire even though it is dormant and subconscious. If Elizabeth should appear in Washington, carrying her baby, if it became known that she had actually given birth to the child and that she had a husband who was the child's father, the women would wreck the Government. The older women would become wild because they had been deprived of what would seem to them to be the greatest privilege and blessing of their sex, while the young girls would refuse to accept the dictates of our government and would try just as hard as they could, to follow Elizabeth's example. There would be chaos."

"Then why did you secretly urge us to go on with it?"

"For two reasons. First as a retribution to your mothers, who decided to kill themselves rather than go through with the operation, and second, because, as scientists, we wanted to make sure it was still possible for a woman to have a child."

"Do you mean that you thought there was a doubt?"

"Certainly! And we had a right to think so. For at least forty generations these physiological functions of both sexes have been unused. We were unable to tell what would happen if a normal man married a normal woman. We did not even know if there were any normal people any more. We tried to find out what the physicians and biologists thought about it, but there again we were in trouble. No one had thought about such a thing for so long, that they could only guess, and, being scientists, they felt that each had to guess differently from the other."

The young man laughed,

"I think we shall be able to tell you the answer some time."

"That is the pity of it. You will be able to tell my friend and you can tell me, but you cannot tell the world. We should be pleased if you had a child, and we would try to arrange to secretly get you a child of the opposite sex so they could grow up together and marry at the right time. If we were only younger, we might even assist you in forming a small race, but it would have to be a race of savages, educated savages, but none the less composed of individuals who had to live under the same conditions that savages used to live under. Well, we have talked enough and I know that you are anxious to return to your wife. Let's go and get whatever you need from my private museum. I want you to take anything you need. We do not want Elizabeth to suffer in any way. Tell her the story I have told you. Tell her that we love her and want her to be a brave girl. Just as soon as you go, I will step over and see her grandfather. Be sure to leave me a good map of just where you are. I wish there was some way of communicating with you, so we could be sent for — if you get into trouble of any kind. We will prepare a medicine chest for you."

An hour later the young man jumped into his plane, kissed the old man good-bye and started out for his long trip back to the cave. In the monoplane were a number of things that would help make the winter more endurable. As soon as he left, the Librarian started out to make a midnight call on his old friend and the two talked till morning; and the things they talked about were the things that had interested young folks thousands of years ago.

The winter was severe. With all his education and effort and even with the use of a lot of common sense, Leuson could not keep the winter from being a hard one. The chimney smoked, the food spoiled, the roof of the cave leaked, the wolves killed and ate their little pig, their few chickens refused to lay, the traps did not catch rabbits regularly, and never a day passed without some new form of trouble, unforeseen and unpreventable. Yet Leuson Hubler was happy with his wife, Elizabeth Sellers, because they lived in a home and the thing that made the cave a home was love.

The winter passed and the spring came. The young man wanted to make another trip to Washington — to see if he could get help, advice or medicine. His wife refused to let him go: she felt that she would die if she had to spend a night alone. Together they studied over the old books and tried to prepare themselves as best they could for the event they now were certain had to be faced. Leuson captured and tamed a wild goat and in May she gave birth to a kid. He felt easier. No matter what happened, there would be milk. Elizabeth laughed at him and said she would tend to that part of the programme, but Leuson only took better care of the goat, and learned to milk it. He also ventured to send a radio message to the Librarian.

June was warm. Elizabeth rarely left the mouth of the cave. For over three weeks she had not been down on the meadow. Every day Leuson would take the goat and the kid down to the pasture. Finally he decided to keep the goat in the cave and bring it grass. He did not want to lose the goat. Elizabeth kept on laughing at him. He would laugh back at her and then go down the path with sorrow in his face and fear in his heart.

On the last of June, Elizabeth stayed in her bed. Leuson stayed by her side. They talked and now and then he gave her milk, warm from the goat. He did for her all he could and she helped herself as well as she was able to remember the instructions in the old books, and all through the night she kept on telling him that she had been happy in her home and their love and that she was glad she was going to have the baby and how proud she was that he was the father of the baby and how much she loved him and how proud they were going to be of their child — and when morning came she died.

The cause of her death was a simple matter. The average physician of the nineteenth century could have saved her. The only reason for her death was that she had given birth to a baby and there was no one there who knew how to care for her in a scientific manner.

Leuson Hubler, the first Father that the world had known for a thousand years, picked his daughter up and carried her into the sunshine. There, on the rock ledge, the kid was nursing the goat. The goat was bleating from hunger and the joy of nursing. Leuson gave her a handful of grain and let the baby drink with the kid.

As he knelt there, giving his daughter her first food, two old men toiled up the steep path. The Librarian and his friend were bringing the medicine that would have saved the life of the first Mother.

They were just a little too late.

That fall, in the city of Washington, the National Society of Federated Women held their annual meeting. Five thousand of the leaders of their sex had gathered for the meeting and every woman in the nation was listening to the proceedings over the radio. It was the one time in the year that the women felt fully their sex consciousness. All through the year they believed that they were the equal of the male sex, but during this week they knew they were superior in every way. The usual programme was presented, the usual leaders of the feminine sex introduced. It was not till Thursday afternoon that the unusual occurred.

A man was introduced to the great audience. It was a distinct novelty, as only rarely was a man invited to take part in the conference.

Leuson Hubler walked out on the platform, carrying a basket which he placed behind the President's chair. Then he started to talk in a voice so clear and musical that there was hardly any need of the loud speakers, and even as he talked to the five thousand leaders of womankind, many more thousands of women in all parts of the land listened to his words over the radio.

He started to tell them about the old days. He talked in simple language, with well chosen words. Largely he repeated what he had said to his bride the first evening in front of the cave. He told about the gradual growth of unrest in the women and selfishness in the men and how with the companionate marriage had come a gradual deterioration of the human race. He went on to explain the gradual growth of the Sterilization Laws and how finally the Synthetic Baby was thought not only necessary, but highly scientific. Next he told of the disappearance of the home and the gradual death of family love. With the home and love had disappeared the father. There remained only houses in which lived men and women who were "married" companions and nothing else. They had children, the seed of dead women, who had never known a husband's love. The children were loved only as permit children.

On and on he talked and as he talked there arose in the hearts of the women who listened a strange unrest and hunger for something that had once been their heritage. They listened and yearned for something they had lost a thousand years ago. Then he told them about Elizabeth and himself; how they were the children of two women who had killed themselves rather than to be denied their righteous inheritance. He told how they had loved each other as boy and girl and as young man and woman had fled to the wilderness rather than submit to the laws of the land. He told how they had lived and loved in the cave, and how they had wondered whether it was still possible for a woman to give birth to a living child: how they had tried to prepare for the emergency — about the goat in case anything happened.

The five thousand women silently rose to their feet: they crowded around the platform where he was weaving his magic spell — and he told about that first night and then about the last night — how she had said that no matter what happened she was repaid by the love and happiness that had been hers that year in the cave home — and then he told how she had died, but that she might have been saved — and that even in her death she had shown to the world that a normal woman could still give birth to a normal child — and then —

He reached down into the basket and, picking up his daughter, held the baby high above the heads of the five thousand women and he showed them a baby, born of the love of a man and a woman in a home.

For a while the hall was silent.

The women looked at the baby, and as the tears streamed down their cheeks, they knew at last what they had been wanting all those thousand years. They knew, but they needed a leader to tell them.

And Dr. Helen Sellers Gowers, large, efficient, determined, shouldered her way to the platform and stood by the man and the baby and said:

"This is the child of the woman I called my sister. She is dead, but we will never forget what she has taught us. I know what I feel and I know what you feel. It is too late for many of us, but it is not too late to save our boys and girls. There must be no more synthetic children, no more companionate husbands, no more mere houses. We can rule the country because we are the stronger. Let us go to Congress and tell the men what they must grant us."

And as they marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, the women of the nation cried in unison:

"Give us back our homes, our husbands and our babies!"