The Girl Who Got Rattled

by Stewart Edward White

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018) is a stylized western movie by the Coen brother consisting of six episodes adapted from short stories. The longest is entitled, "The Gal Who Got Rattled" which is clearly an enhanced version of short story The Girl Who Got Rattled. It's a rather interesting exercise, on your own or in a classroom, to think about and discuss the changes and enhancements that distinguish the film version from the original. What changes did the Coens make to the story line, characters and final dramatic scenes and to what effect?

This is one of the stories of Alfred. There are many of them still floating around the West, for Alfred was in his time very well known. He was a little man, and he was bashful. That is the most that can be said against him; but he was very little and very bashful. When on horseback his legs hardly reached the lower body-line of his mount, and only his extreme agility enabled him to get on successfully. When on foot, strangers were inclined to call him "sonny." In company he never advanced an opinion. If things did not go according to his ideas, he reconstructed the ideas, and made the best of it--only he could make the most efficient best of the poorest ideas of any man on the plains. His attitude was a perpetual sidling apology. It has been said that Alfred killed his men diffidently, without enthusiasm, as though loth to take the responsibility, and this in the pioneer days on the plains was either frivolous affectation, or else--Alfred. With women he was lost. Men would have staked their last ounce of dust at odds that he had never in his life made a definite assertion of fact to one of the opposite sex. When it became absolutely necessary to change a woman's preconceived notions as to what she should do--as, for instance, discouraging her riding through quicksand--he would persuade somebody else to issue the advice. And he would cower in the background blushing his absurd little blushes at his second-hand temerity. Add to this narrow, sloping shoulders, a soft voice, and a diminutive pink-and-white face.

But Alfred could read the prairie like a book. He could ride anything, shoot accurately, was at heart afraid of nothing, and could fight like a little catamount when occasion for it really arose. Among those who knew, Alfred was considered one of the best scouts on the plains. That is why Caldwell, the capitalist, engaged him when he took his daughter out to Deadwood.

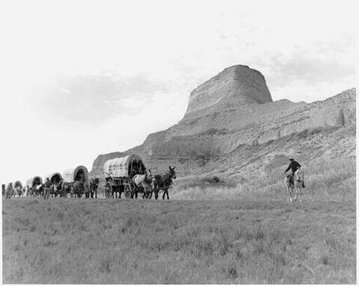

Miss Caldwell was determined to go to Deadwood. A limited experience of the lady's sort, where they have wooden floors to the tents, towels to the tent-poles, and expert cooks to the delectation of the campers, had convinced her that "roughing it" was her favorite recreation. So, of course, Caldwell senior had, sooner or later, to take her across the plains on his annual trip. This was at the time when wagon-trains went by way of Pierre on the north, and the South Fork on the south. Incidental Indians, of homicidal tendencies and undeveloped ideas as to the propriety of doing what they were told, made things interesting occasionally, but not often. There was really no danger to a good-sized train.

The daughter had a fiance named Allen who liked roughing it, too; so he went along. He and Miss Caldwell rigged themselves out bountifully, and prepared to enjoy the trip.

At Pierre the train of eight wagons was made up, and they were joined by Alfred and Billy Knapp. These two men were interesting, but tyrannical on one or two points--such as getting out of sight of the train, for instance. They were also deficient in reasons for their tyranny. The young people chafed, and, finding Billy Knapp either imperturbable or thick-skinned, they turned their attention to Alfred. Allen annoyed Alfred, and Miss Caldwell thoughtlessly approved of Allen. Between them they succeeded often in shocking fearfully all the little man's finer sensibilities. If it had been a question of Allen alone, the annoyance would soon have ceased. Alfred would simply have bashfully killed him. But because of his innate courtesy, which so saturated him that his philosophy of life was thoroughly tinged by it, he was silent and inactive.

There is a great deal to recommend a plains journey at first. Later, there is nothing at all to recommend it. It has the same monotony as a voyage at sea, only there is less living room, and, instead of being carried, you must progress to a great extent by your own volition. Also the food is coarse, the water poor, and you cannot bathe. To a plainsman, or a man who has the instinct, these things are as nothing in comparison with the charm of the outdoor life, and the pleasing tingling of adventure. But woman is a creature wedded to comfort. She also has a strange instinctive desire to be entirely alone every once in a while, probably because her experiences, while not less numerous than man's, are mainly psychical, and she needs occasionally time to get "thought up to date." So Miss Caldwell began to get very impatient.

The afternoon of the sixth day Alfred, Miss Caldwell, and Allen rode along side by side. Alfred was telling a self-effacing story of adventure, and Miss Caldwell was listening carelessly because she had nothing else to do. Allen chaffed lazily when the fancy took him.

"I happened to have a limb broken at the time," Alfred was observing, parenthetically, in his soft tones, "and so----"

"What kind of a limb?" asked the young Easterner, with direct brutality. He glanced with a half-humourous aside at the girl, to whom the little man had been mainly addressing himself.

Alfred hesitated, blushed, lost the thread of his tale, and finally in great confusion reined back his horse by the harsh Spanish bit. He fell to the rear of the little wagon-train, where he hung his head, and went hot and cold by turns in thinking of such an indiscretion before a lady.

The young Easterner spurred up on the right of the girl's mount.

"He's the queerest little fellow I ever saw!" he observed, with a laugh. "Sorry to spoil his story. Was it a good one?"

"It might have been if you hadn't spoiled it," answered the girl, flicking her horse's ears mischievously. The animal danced. "What did you do it for?"

"Oh, just to see him squirm. He'll think about that all the rest of the afternoon, and will hardly dare look you in the face next time you meet."

"I know. Isn't he funny? The other morning he came around the corner of the wagon and caught me with my hair down. I wish you could have seen him!"

She laughed gayly at the memory.

"Let's get ahead of the dust," she suggested.

They drew aside to the firm turf of the prairie and put their horses to a slow lope. Once well ahead of the canvas-covered schooners they slowed down to a walk again.

"Alfred says we'll see them to-morrow," said the girl.

"See what?"

"Why, the Hills! They'll show like a dark streak, down past that butte there--what's its name?"

"Porcupine Tail."

"Oh, yes. And after that it's only three days. Are you glad?"

"Are you?"

"Yes, I believe I am. This life is fun at first, but there's a certain monotony in making your toilet where you have to duck your head because you haven't room to raise your hands, and this barrelled water palls after a time. I think I'll be glad to see a house again. People like camping about so long----"

"It hasn't gone back on me yet."

"Well, you're a man and can do things."

"Can't you do things?"

"You know I can't. What do you suppose they'd say if I were to ride out just that way for two miles? They'd have a fit."

"Who'd have a fit? Nobody but Alfred, and I didn't know you'd gotten afraid of him yet! I say, just let's! We'll have a race, and then come right back." The young man looked boyishly eager.

"It would be nice," she mused. They gazed into each other's eyes like a pair of children, and laughed.

"Why shouldn't we?" urged the young man. "I'm dead sick of staying in the moving circle of these confounded wagons. What's the sense of it all, anyway?"

"Why, Indians, I suppose," said the girl, doubtfully.

"Indians!" he replied, with contempt. "Indians! We haven't seen a sign of one since we left Pierre. I don't believe there's one in the whole blasted country. Besides, you know what Alfred said at our last camp?"

"What did Alfred say?"

"Alfred said he hadn't seen even a teepee-trail, and that they must be all up hunting buffalo. Besides that, you don't imagine for a moment that your father would take you all this way to Deadwood just for a lark, if there was the slightest danger, do you?"

"I don't know; I made him."

She looked out over the long sweeping descent to which they were coming, and the long sweeping ascent that lay beyond. The breeze and the sun played with the prairie grasses, the breeze riffling them over, and the sun silvering their under surfaces thus exposed. It was strangely peaceful, and one almost expected to hear the hum of bees as in a New England orchard. In it all was no sign of life.

"We'd get lost," she said, finally.

"Oh, no, we wouldn't!" he asserted with all the eagerness of the amateur plainsman. "I've got that all figured out. You see, our train is going on a line with that butte behind us and the sun. So if we go ahead, and keep our shadows just pointing to the butte, we'll be right in their line of march."

He looked to her for admiration of his cleverness. She seemed convinced. She agreed, and sent him back to her wagon for some article of invented necessity. While he was gone she slipped softly over the little hill to the right, cantered rapidly over two more, and slowed down with a sigh of satisfaction. One alone could watch the directing shadow as well as two. She was free and alone. It was the one thing she had desired for the last six days of the long plains journey, and she enjoyed it now to the full. No one had seen her go. The drivers droned stupidly along, as was their wont; the occupants of the wagons slept, as was their wont; and the diminutive Alfred was hiding his blushes behind clouds of dust in the rear, as was not his wont at all. He had been severely shocked, and he might have brooded over it all the afternoon, if a discovery had not startled him to activity.

On a bare spot of the prairie he discerned the print of a hoof. It was not that of one of the train's animals. Alfred knew this, because just to one side of it, caught under a grass-blade so cunningly that only the little scout's eyes could have discerned it at all, was a single blue bead. Alfred rode out on the prairie to right and left, and found the hoof-prints of about thirty ponies. He pushed his hat back and wrinkled his brow, for the one thing he was looking for he could not find--the two narrow furrows made by the ends of teepee-poles dragging along on either side of the ponies. The absence of these indicated that the band was composed entirely of bucks, and bucks were likely to mean mischief.

He pushed ahead of the whole party, his eyes fixed earnestly on the ground. At the top of the hill he encountered the young Easterner. The latter looked puzzled, in a half-humourous way.

"I left Miss Caldwell here a half-minute ago," he observed to Alfred, "and I guess she's given me the slip. Scold her good for me when she comes in--will you?" He grinned, with good-natured malice at the idea of Alfred's scolding anyone.

Then Alfred surprised him.

The little man straightened suddenly in his saddle and uttered a fervent curse. After a brief circle about the prairie, he returned to the young man.

"You go back to th' wagons, and wake up Billy Knapp, and tell him this--that I've gone scoutin' some, and I want him to watch out. Understand? Watch out!"

"What?" began the Easterner, bewildered.

"I'm a-goin' to find her," said the little man, decidedly.

"You don't think there's any danger, do you?" asked the Easterner, in anxious tones. "Can't I help you?"

"You do as I tell you," replied the little man, shortly, and rode away.

He followed Miss Caldwell's trail quite rapidly, for the trail was fresh. As long as he looked intently for hoof-marks, nothing was to be seen, the prairie was apparently virgin; but by glancing the eye forty or fifty yards ahead, a faint line was discernible through the grasses.

Alfred came upon Miss Caldwell seated quietly on her horse in the very centre of a prairie-dog town, and so, of course, in the midst of an area of comparatively desert character. She was amusing herself by watching the marmots as they barked, or watched, or peeped at her, according to their distance from her. The sight of Alfred was not welcome, for he frightened the marmots.

When he saw Miss Caldwell, Alfred grew bashful again. He sidled his horse up to her and blushed.

"I'll show you th' way back, miss," he said, diffidently.

"Thank you," replied Miss Caldwell, with a slight coldness, "I can find my own way back."

"Yes, of course," hastened Alfred, in an agony. "But don't you think we ought to start back now? I'd like to go with you, miss, if you'd let me. You see the afternoon's quite late."

Miss Caldwell cast a quizzical eye at the sun.

"Why, it's hours yet till dark!" she said, amusedly.

Then Alfred surprised Miss Caldwell.

His diffident manner suddenly left him. He jumped like lightning from his horse, threw the reins over the animal's head so he would stand, and ran around to face Miss Caldwell.

"Here, jump down!" he commanded.

The soft Southern burr of his ordinary conversation had given place to a clear incisiveness. Miss Caldwell looked at him amazed.

Seeing that she did not at once obey, Alfred actually began to fumble hastily with the straps that held her riding-skirt in place. This was so unusual in the bashful Alfred that Miss Caldwell roused and slipped lightly to the ground.

"Now what?" she asked.

Alfred, without replying, drew the bit to within a few inches of the animal's hoofs, and tied both fetlocks firmly together with the double-loop. This brought the pony's nose down close to his shackled feet. Then he did the same thing with his own beast. Thus neither animal could so much as hobble one way or the other. They were securely moored.

Alfred stepped a few paces to the eastward. Miss Caldwell followed.

"Sit down," said he.

Miss Caldwell obeyed with some nervousness. She did not understand at all, and that made her afraid. She began to have a dim fear lest Alfred might have gone crazy. His next move strengthened this suspicion. He walked away ten feet and raised his hand over his head, palm forward. She watched him so intently that for a moment she saw nothing else. Then she followed the direction of his gaze, and uttered a little sobbing cry.

Just below the sky-line of the first slope to eastward was silhouetted a figure on horseback. The figure on horseback sat motionless.

"We're in for fight," said Alfred, coming back after a moment. "He won't answer my peace-sign, and he's a Sioux. We can't make a run for it through this dog-town. We've just got to stand 'em off."

He threw down and back the lever of his old 44 Winchester, and softly uncocked the arm. Then he sat down by Miss Caldwell.

From various directions, silently, warriors on horseback sprang into sight and moved dignifiedly toward the first-comer, forming at the last a band of perhaps thirty men. They talked together for a moment, and then one by one, at regular intervals, detached themselves and began circling at full speed to the left, throwing themselves behind their horses, and yelling shrill-voiced, but firing no shot as yet.

"They'll rush us," speculated Alfred. "We're too few to monkey with this way. This is a bluff."

The circle about the two was now complete. After watching the whirl of figures a few minutes, and the motionless landscape beyond, the eye became dizzied and confused.

"They won't have no picnic," went on Alfred, with a little chuckle. "Dog-hole's as bad fer them as fer us. They don't know how to fight. If they was to come in on all sides, I couldn't handle 'em, but they always rush in a bunch, like damn fools!" and then Alfred became suffused with blushes, and commenced to apologise abjectly and profusely to a girl who had heard neither the word nor its atonement. The savages and the approaching fight were all she could think of.

Suddenly one of the Sioux threw himself forward under his horse's neck and fired. The bullet went wild, of course, but it shrieked with the rising inflection of a wind-squall through bared boughs, seeming to come ever nearer. Miss Caldwell screamed and covered her face. The savages yelled in chorus.

The one shot seemed to be the signal for a spattering fire all along the line. Indians never clean their rifles, rarely get good ammunition, and are deficient in the philosophy of hind-sights. Besides this, it is not easy to shoot at long range in a constrained position from a running horse. Alfred watched them contemptuously in silence.

"If they keep that up long enough, the wagon-train may hear 'em," he said, finally. "Wisht we weren't so far to nor-rard. There, it's comin'!" he said, more excitedly.

The chief had paused, and, as the warriors came to him, they threw their ponies back on their haunches, and sat motionless. They turned, the ponies' heads toward the two.

Alfred arose deliberately for a better look.

"Yes, that's right," he said to himself, "that's old Lone Pine, sure thing. I reckon we-all's got to make a good fight!"

The girl had sunk to the ground, and was shaking from head to foot. It is not nice to be shot at in the best of circumstances, but to be shot at by odds of thirty to one, and the thirty of an out-landish and terrifying species, is not nice at all. Miss Caldwell had gone to pieces badly, and Alfred looked grave. He thoughtfully drew from its holster his beautiful Colt's with its ivory handle, and laid it on the grass. Then he blushed hot and cold, and looked at the girl doubtfully. A sudden movement in the group of savages, as the war-chief rode to the front, decided him.

"Miss Caldwell," he said.

The girl shivered and moaned.

Alfred dropped to his knees and shook her shoulder roughly.

"Look up here," he commanded. "We ain't got but a minute."

Composed a little by the firmness of his tone, she sat up. Her face had gone chalky, and her hair had partly fallen over her eyes.

"Now, listen to every word," he said, rapidly. "Those Injins is goin' to rush us in a minute. P'r'aps I can break them, but I don't know. In that pistol there, I'll always save two shots--understand?--it's always loaded. If I see it's all up, I'm a-goin' to shoot you with one of 'em, and myself with the other."

"Oh!" cried the girl, her eyes opening wildly. She was paying close enough attention now.

"And if they kill me first"--he reached forward and seized her wrist impressively--"if they kill me first, you must take that pistol and shoot yourself. Understand? Shoot yourself--in the head--here!"

He tapped his forehead with a stubby forefinger.

The girl shrank back in horror. Alfred snapped his teeth together and went on grimly.

"If they get hold of you," he said, with solemnity, "they'll first take off every stitch of your clothes, and when you're quite naked they'll stretch you out on the ground with a raw-hide to each of your arms and legs. And then they'll drive a stake through the middle of your body into the ground--and leave you there--to die--slowly!"

And the girl believed him, because, incongruously enough, even through her terror she noticed that at this, the most immodest speech of his life, Alfred did not blush. She looked at the pistol lying on the turf with horrified fascination.

The group of Indians, which had up to now remained fully a thousand yards away, suddenly screeched and broke into a run directly toward the dog-town.

There is an indescribable rush in a charge of savages. The little ponies make their feet go so fast, the feathers and trappings of the warriors stream behind so frantically, the whole attitude of horse and man is so eager, that one gets an impression of fearful speed and resistless power. The horizon seems full of Indians.

As if this were not sufficiently terrifying, the air is throbbing with sound. Each Indian pops away for general results as he comes jumping along, and yells shrilly to show what a big warrior he is, while underneath it all is the hurried monotone of hoof-beats becoming ever louder, as the roar of an increasing rainstorm on the roof. It does not seem possible that anything can stop them.

Yet there is one thing that can stop them, if skilfully taken advantage of, and that is their lack of discipline. An Indian will fight hard when cornered, or when heated by lively resistance, but he hates to go into it in cold blood. As he nears the opposing rifle, this feeling gets stronger. So often a man with nerve enough to hold his fire, can break a fierce charge merely by waiting until it is within fifty yards or so, and then suddenly raising the muzzle of his gun. If he had gone to shooting at once, the affair would have become a combat, and the Indians would have ridden him down. As it is, each has had time to think. By the time the white man is ready to shoot, the suspense has done its work. Each savage knows that but one will fall, but, cold-blooded, he does not want to be that one; and, since in such disciplined fighters it is each for himself, he promptly ducks behind his mount and circles away to the right or the left. The whole band swoops and divides, like a flock of swift-winged terns on a windy day.

This Alfred relied on in the approaching crisis.

The girl watched the wild sweep of the warriors with strained eyes. She had to grasp her wrist firmly to keep from fainting, and she seemed incapable of thought. Alfred sat motionless on a dog-mound, his rifle across his lap. He did not seem in the least disturbed.

"It's good to fight again," he murmured, gently fondling the stock of his rifle. "Come on, ye devils! Oho!" he cried as a warrior's horse went down in a dog-hole, "I thought so!"

His eyes began to shine.

The ponies came skipping here and there, nimbly dodging in and out between the dog-holes. Their riders shot and yelled wildly, but none of the bullets went lower than ten feet. The circle of their advance looked somehow like the surge shoreward of a great wave, and the similarity was heightened by the nodding glimpses of the light eagles' feathers in their hair.

The run across the honey-combed plain was hazardous--even to Indian ponies--and three went down kicking, one after the other. Two of the riders lay stunned. The third sat up and began to rub his knee. The pony belonging to Miss Caldwell, becoming frightened, threw itself and lay on its side, kicking out frantically with its hind legs.

At the proper moment Alfred cocked his rifle and rose swiftly to his knees. As he did so, the mound on which he had been kneeling caved into the hole beneath it, and threw him forward on his face. With a furious curse, he sprang to his feet and levelled his rifle at the thick of the press. The scheme worked. In a flash every savage disappeared behind his pony, and nothing was to be seen but an arm and a leg. The band divided on either hand as promptly as though the signal for such a drill had been given, and swept gracefully around in two long circles until it reined up motionless at nearly the exact point from which it had started on its imposing charge. Alfred had not fired a shot.

He turned to the girl with a short laugh.

She lay face upward on the ground, staring at the sky with wide-open, horror-stricken eyes. In her brow was a small blackened hole, and under her head, which lay strangely flat against the earth, the grasses had turned red. Near her hand lay the heavy Colt's 44.

Alfred looked at her a minute without winking. Then he nodded his head.

"It was 'cause I fell down that hole--she thought they'd got me!" he said aloud to himself. "Pore little gal! She hadn't ought to have did it!"

He blushed deeply, and, turning his face away, pulled down her skirt until it covered her ankles. Then he picked up his Winchester and fired three shots. The first hit directly back of the ear one of the stunned Indians who had fallen with his horse. The second went through the other stunned Indian's chest. The third caught the Indian with the broken leg between the shoulders just as he tried to get behind his struggling pony.

Shortly after, Billy Knapp and the wagon-train came along.

This story is featured in our collection of Short Stories for High School. You may also enjoy All Gold Canyon by Jack London, also featured in The Coen Brothers' The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

Want to save this story?

Create a free account to build your personal library of favorite stories

Sign Up - It's Free!Already have an account? Log in