How the Captain Made Christmas

by Thomas Nelson Page

Published in his collection of short stories titled The Burial of the Guns (1894). it's about the importance of where you are from-- a young man's retelling of a memorable train ride in which the captain shared his stories of love and life to an appreciate group of no-longer strangers once they arrived in New Orleans for Christmas.

It was just a few days before Christmas, and the men around the large fireplace at the club had, not unnaturally, fallen to talking of Christmas. They were all men in the prime of life, and all or nearly all of them were from other parts of the country; men who had come to the great city to make their way in life, and who had, on the whole, made it in one degree or another, achieving sufficient success in different fields to allow of all being called successful men. Yet, as the conversation had proceeded, it had taken a reminiscent turn. When it began, only three persons were engaged in it, two of whom, McPheeters and Lesponts, were in lounging-chairs, with their feet stretched out towards the log fire, while the third, Newton, stood with his back to the great hearth, and his coat-tails well divided. The other men were scattered about the room, one or two writing at tables, three or four reading the evening papers, and the rest talking and sipping whiskey and water, or only talking or only sipping whiskey and water. As the conversation proceeded around the fireplace, however, one after another joined the group there, until the circle included every man in the room.

It had begun by Lesponts, who had been looking intently at Newton for some moments as he stood before the fire with his legs well apart and his eyes fastened on the carpet, breaking the silence by asking, suddenly: "Are you going home?"

"I don't know," said Newton, doubtfully, recalled from somewhere in dreamland, but so slowly that a part of his thoughts were still lingering there. "I haven't made up my mind -- I'm not sure that I can go so far as Virginia, and I have an invitation to a delightful place -- a house-party near here."

"Newton, anybody would know that you were a Virginian," said McPheeters, "by the way you stand before that fire."

Newton said, "Yes," and then, as the half smile the charge had brought up died away, he said, slowly, "I was just thinking how good it felt, and I had gone back and was standing in the old parlor at home the first time I ever noticed my father doing it; I remember getting up and standing by him, a little scrap of a fellow, trying to stand just as he did, and I was feeling the fire, just now, just as I did that night. That was -- thirty-three years ago," said Newton, slowly, as if he were doling the years from his memory.

"Newton, is your father living?" asked Lesponts. "No, but my mother is," he said; "she still lives at the old home in the country."

From this the talk had gone on, and nearly all had contributed to it, even the most reticent of them, drawn out by the universal sympathy which the subject had called forth. The great city, with all its manifold interests, was forgotten, and the men of the world went back to their childhood and early life in little villages or on old plantations, and told incidents of the time when the outer world was unknown, and all things had those strange and large proportions which the mind of childhood gives. Old times were ransacked and Christmas experiences in them were given without stint, and the season was voted, without dissent, to have been far ahead of Christmas now. Presently, one of the party said: "Did any of you ever spend a Christmas on the cars? If you have not, thank Heaven, and pray to be preserved from it henceforth, for I've done it, and I tell you it's next to purgatory. I spent one once, stuck in a snow-drift, or almost stuck, for we were ten hours late, and missed all connections, and the Christmas I had expected to spend with friends, I passed in a nasty car with a surly Pullman conductor, an impudent mulatto porter, and a lot of fools, all of whom could have murdered each other, not to speak of a crying baby whose murder was perhaps the only thing all would have united on."

This harsh speech showed that the subject was about exhausted, and someone, a man who had come in only in time to hear the last speaker, had just hazarded the remark, in a faint imitation of an English accent, that the sub-officials in this country were a surly, ill-conditioned lot, anyhow, and always were as rude as they dared to be, when Lesponts, who had looked at the speaker lazily, said:

"Yes, I have spent a Christmas on a sleeping-car, and, strange to say, I have a most delightful recollection of it."

This was surprising enough to have gained him a hearing anyhow, but the memory of the occasion was evidently sufficiently strong to carry Lesponts over obstacles, and he went ahead.

"Has any of you ever taken the night train that goes from here South through the Cumberland and Shenandoah Valleys, or from Washington to strike that train?"

No one seemed to have done so, and he went on:

"Well, do it, and you can even do it Christmas, if you get the right conductor. It's well worth doing the first chance you get, for it's almost the prettiest country in the world that you go through; there is nothing that I've ever seen lovelier than parts of the Cumberland and Shenandoah Valleys, and the New River Valley is just as pretty, -- that background of blue beyond those rolling hills, and all, -- you know, McPheeters?" McPheeters nodded, and he proceeded:

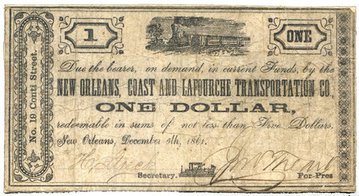

"I always go that way now when I go South. Well, I went South one winter just at Christmas, and I took that train by accident. I was going to New Orleans to spend Christmas, and had expected to have gotten off to be there several days beforehand, but an unlooked-for matter had turned up and prevented my getting away, and I had given up the idea of going, when I changed my mind: the fact is, I was in a row with a friend of mine there. I decided, on the spur of the moment, to go, anyhow, and thus got off on the afternoon train for Washington, intending to run my luck for getting a sleeper there. This was the day before Christmas-eve and I was due to arrive in New Orleans Christmas-day, some time. Well, when I got to Washington there was not a berth to be had for love or money, and I was in a pickle. I fumed and fussed; abused the railroad companies and got mad with the ticket agent, who seemed, I thought, to be very indifferent as to whether I went to New Orleans or not, and I had just decided to turn around and come back to New York, when the agent, who was making change for someone else, said: `I'm not positive, but I think there's a train on such and such a road, and you may be able to get a berth on that. It leaves about this time, and if you hurry you may be able to catch it.' He looked at his watch: `Yes, you've just about time to stand a chance; everything is late to-day, there are such crowds, and the snow and all.' I thanked him, feeling like a dog over my ill-temper and rudeness to him, and decided to try. Anything was better than New York, Christmas-day. So I jumped into a carriage and told the driver to drive like the -- the wind, and he did. When we arrived at the station the ticket agent could not tell me whether I could get a berth or not, the conductor had the diagram out at the train, but he thought there was not the slightest chance. I had gotten warmed up, however, by my friend's civility at the other station, and I meant to go if there was any way to do it, so I grabbed up my bags and rushed out of the warm depot into the cold air again. I found the car and the conductor standing outside of it by the steps. The first thing that struck me was his appearance. Instead of being the dapper young naval-officerish-looking fellow I was accustomed to, he was a stout, elderly man, with bushy, gray hair and a heavy, grizzled mustache, who looked like an old field-marshal. He was surrounded by quite a number of people all crowding about him and asking him questions at once, some of whose questions he was answering slowly as he pored over his diagram, and others of which he seemed to be ignoring. Some were querulous, some good-natured, and all impatient, but he answered them all with imperturbable good humor. It was very cold, so I pushed my way into the crowd. As I did so I heard him say to someone: `You asked me if the lower berths were all taken, did you not?' `Yes, five minutes ago!' snapped the fellow, whom I had already heard swearing, on the edge of the circle. `Well, they are all taken, just as they were the first time I told you they were,' he said, and opened a despatch given him by his porter, a tall, black, elderly negro with gray hair. I pushed my way in and asked him, in my most dulcet tone, if I could get an upper berth to New Orleans. I called him `Captain', thinking him a pompous old fellow. He was just beginning to speak to someone else, but I caught him and he looked across the crowd and said `New Orleans!' My heart sank at the tone, and he went on talking to some other man. `I told you that I would give you a lower berth, sir, I can give you one now, I have just got a message that the person who had "lower two" will not want it.' `Hold on, then, I'll take that lower,' called the man who had spoken before, over the crowd, `I spoke for it first.' `No you won't,' said the Captain, who went on writing. The man pushed his way in angrily, a big, self-assertive fellow; he was evidently smarting from his first repulse. `What's that? I did, I say. I was here before that man got here, and asked you for a lower berth, and you said they were all taken.' The Captain stopped and looked at him. `My dear sir, I know you did; but this gentleman has a lady along.' But the fellow was angry. `I don't care,' he said, `I engaged the berth and I know my rights; I mean to have that lower berth, or I'll see which is bigger, you or Mr. Pullman.' Just then a lady, who had come out on the steps, spoke to the Captain about her seat in the car. He turned to her: `My dear madam, you are all right, just go in there and take your seat anywhere; when I come in I will fix everything. Go straight into that car and don't come out in this cold air any more.' The lady went back and the old fellow said, `Nick, go in there and seat that lady, if you have to turn every man out of his seat.' Then, as the porter went in, he turned back to his irate friend. `Now, my dear sir, you don't mean that: you'd be the first man to give up your berth; this gentleman has his sick wife with him and has been ordered to take her South immediately, and she's going to have a lower berth if I turn every man in that car out, and if you were Mr. Pullman himself I'd tell you the same thing.' The man fell back, baffled and humbled, and we all enjoyed it. Still, I was without a berth, so, with some misgiving, I began: `Captain?' He turned to me. `Oh! you want to go to New Orleans?' `Yes, to spend Christmas; any chance for me?' He looked at his watch. `My dear young sir,' he said, `go into the car and take a seat, and I'll do the best I can with you.' I went in, not at all sure that I should get a berth.

"This, of course, was only a part of what went on, but the crowd had gotten into a good humor and was joking, and I had fallen into the same spirit. The first person I looked for when I entered the car was, of course, the sick woman. I soon picked her out: a sweet, frail-looking lady, with that fatal, transparent hue of skin and fine complexion. She was all muffled up, although the car was very warm. Every seat was either occupied or piled high with bags. Well, the train started, and in a little while the Captain came in, and the way that old fellow straightened things out was a revelation. He took charge of the car and ran it as if he had been the Captain of a boat. At first some of the passengers were inclined to grumble, but in a little while they gave in. As for me, I had gotten an upper berth and felt satisfied. When I waked up next morning, however, we were only a hundred and fifty miles from Washington, and were standing still. The next day was Christmas, and every passenger on the train, except the sick lady and her husband, and the Captain, had an engagement for Christmas dinner somewhere a thousand miles away. There had been an accident on the road. The train which was coming north had jumped the track at a trestle and torn a part of it away. Two or three of the trainmen had been hurt. There was no chance of getting by for several hours more. It was a blue party that assembled in the dressing-room, and more than one cursed his luck. One man was talking of suing the company. I was feeling pretty gloomy myself, when the Captain came in. `Well, gentlemen, `Christmas-gift'; it's a fine morning, you must go out and taste it,' he said, in a cheery voice, which made me feel fresher and better at once, and which brought a response from every man in the dressing-room. Someone asked promptly how long we should be there. `I can't tell you, sir, but some little time; several hours.' There was a groan. `You'll have time to go over the battle-field,' said the Captain, still cheerily. `We are close to the field of one of the bitterest battles of the war.' And then he proceeded to tell us about it briefly. He said, in answer to a question, that he had been in it. `On which side, Captain?' asked someone. `Sir!' with some surprise in his voice. `On which side?' `On our side, sir, of course.' We decided to go over the field, and after breakfast we did.

"The Captain walked with us over the ground and showed us the lines of attack and defence; pointed out where the heaviest fighting was done, and gave a graphic account of the whole campaign. It was the only battle-field I had ever been over, and I was so much interested that when I got home I read up the campaign, and that set me to reading up on the whole subject of the war. We walked back over the hills, and I never enjoyed a walk more. I felt as if I had got new strength from the cold air. The old fellow stopped at a little house on our way back, and went in whilst we waited. When he came out he had a little bouquet of geranium leaves and lemon verbena which he had got. I had noticed them in the window as we went by, and when I saw the way the sick lady looked when he gave them to her, I wished I had brought them instead of him. Some one intent on knowledge asked him how much he paid for them?

"He said, `Paid for them! Nothing.'

"`Did you know them before?' he asked.

"`No, sir.' That was all.

"A little while afterwards I saw him asleep in a seat, but when the train started he got up.

"The old Captain by this time owned the car. He was not only an official, he was a host, and he did the honors as if he were in his own house and we were his guests; all was done so quietly and unobtrusively, too; he pulled up a blind here, and drew one down there, just a few inches, `to give you a little more light on your book, sir'; -- `to shut out a little of the glare, madam -- reading on the cars is a little more trying to the eyes than one is apt to fancy.' He stopped to lean over and tell you that if you looked out of your window you would see what he thought one of the prettiest views in the world; or to mention the fact that on the right was one of the most celebrated old places in the State, a plantation which had once belonged to Colonel So-and-So, `one of the most remarkable men of his day, sir.'

"His porter, Nicholas, was his admirable second; not a porter at all, but a body-servant; as different from the ordinary Pullman-car porter as light from darkness. In fact, it turned out that he had been an old servant of the Captain's. I happened to speak of him to the Captain, and he said: `Yes, sir, he's a very good boy; I raised him, or rather, my father did; he comes of a good stock; plenty of sense and know their places. When I came on the road they gave me a mulatto fellow whom I couldn't stand, one of these young, new, "free-issue" some call them, sir, I believe; I couldn't stand him, I got rid of him.' I asked him what was the trouble. `Oh! no trouble at all, sir; he just didn't know his place, and I taught him. He could read and write a little -- a negro is very apt to think, sir, that if he can write he is educated -- he could write, and thought he was educated; he chewed a toothpick and thought he was a gentleman. I soon taught him better. He was impertinent, and I put him off the train. After that I told them that I must have my own servant if I was to remain with them, and I got Nick. He is an excellent boy (he was about fifty-five). The black is a capital servant, sir, when he has sense, far better than the mulatto.'

"I became very intimate with the old fellow. You could not help it. He had a way about him that drew you out. I told him I was going to New Orleans to pay a visit to friends there. He said, `Got a sweetheart there?' I was rather taken aback; but I told him, `Yes.' He said he knew it as soon as I spoke to him on the platform. He asked me who she was, and I told him her name. He said to me, `Ah! you lucky dog.' I told him I did not know that I was not most unlucky, for I had no reason to think she was going to marry me. He said, `You tell her I say you'll be all right.' I felt better, especially when the old chap said, `I'll tell her so myself.' He knew her. She always travelled with him when she came North, he said.

"I did not know at all that I was all right; in fact, I was rather low down just then about my chances, which was the only reason I was so anxious to go to New Orleans, and I wanted just that encouragement and it helped me mightily. I began to think Christmas on the cars wasn't quite so bad after all. He drew me on, and before I knew it I had told him all about myself. It was the queerest thing; I had no idea in the world of talking about my matters. I had hardly ever spoken of her to a soul; but the old chap had a way of making you feel that he would be certain to understand you, and could help you. He told me about his own case, and it wasn't so different from mine. He lived in Virginia before the war; came from up near Lynchburg somewhere; belonged to an old family there, and had been in love with his sweetheart for years, but could never make any impression on her. She was a beautiful girl, he said, and the greatest belle in the country round. Her father was one of the big lawyers there, and had a fine old place, and the stable was always full of horses of the young fellows who used to be coming to see her, and `she used to make me sick, I tell you,' he said, `I used to hate 'em all; I wasn't afraid of 'em; but I used to hate a man to look at her; it seemed so impudent in him; and I'd have been jealous if she had looked at the sun. Well, I didn't know what to do. I'd have been ready to fight 'em all for her, if that would have done any good, but it wouldn't; I didn't have any right to get mad with 'em for loving her, and if I had got into a row she'd have sent me off in a jiffy. But just then the war came on, and it was a Godsend to me. I went in first thing. I made up my mind to go in and fight like five thousand furies, and I thought maybe that would win her, and it did; it worked first-rate. I went in as a private, and I got a bullet through me in about six months, through my right lung, that laid me off for a year or so; then I went back and the boys made me a lieutenant, and when the captain was made a major, I was made captain. I was offered something higher once or twice, but I thought I'd rather stay with my company; I knew the boys, and they knew me, and we had got sort of used to each other -- to depending on each other, as it were. The war fixed me all right, though. When I went home that first time my wife had come right around, and as soon as I was well enough we were married. I always said if I could find that Yankee that shot me I'd like to make him a present. I found out that the great trouble with me had been that I had not been bold enough; I used to let her go her own way too much, and seemed to be afraid of her. I WAS afraid of her, too. I bet that's your trouble, sir: are you afraid of her?' I told him I thought I was. `Well, sir,' he said, `it will never do; you mustn't let her think that -- never. You cannot help being afraid of her, for every man is that; but it is fatal to let her know it. Stand up, sir, stand up for your rights. If you are bound to get down on your knees -- and every man feels that he is -- don't do it; get up and run out and roll in the dust outside somewhere where she can't see you. Why, sir,' he said, `it doesn't do to even let her think she's having her own way; half the time she's only testing you, and she doesn't really want what she pretends to want. Of course, I'm speaking of before marriage; after marriage she always wants it, and she's going to have it, anyway, and the sooner you find that out and give in, the better. You must consider this, however, that her way after marriage is always laid down to her with reference to your good. She thinks about you a great deal more than you do about her, and she's always working out something that is for your advantage; she'll let you do some things as you wish, just to make you believe you are having your own way, but she's just been pretending to think otherwise, to make you feel good.'

"This sounded so much like sense that I asked him how much a man ought to stand from a woman. `Stand, sir?' he said; `why, everything, everything that does not take away his self-respect.' I said I believed if he'd let a woman do it she'd wipe her shoes on him. `Why, of course she will,' he said, `and why shouldn't she? A man is not good enough for a good woman to wipe her shoes on. But if she's the right sort of a woman she won't do it in company, and she won't let others do it at all; she'll keep you for her own wiping.'"

"There's a lot of sense in that, Lesponts," said one of his auditors, at which there was a universal smile of assent. Lesponts said he had found it out, and proceeded.

"Well, we got to a little town in Virginia, I forget the name of it, where we had to stop a short time. The Captain had told me that his home was not far from there, and his old company was raised around there. Quite a number of the old fellows lived about there yet, he said, and he saw some of them nearly every time he passed through, as they `kept the run of him.' He did not know that he'd `find any of them out to-day, as it was Christmas, and they would all be at home,' he said. As the train drew up I went out on the platform, however, and there was quite a crowd assembled. I was surprised to find it so quiet, for at other places through which we had passed they had been having high jinks: firing off crackers and making things lively. Here the crowd seemed to be quiet and solemn, and I heard the Captain's name. Just then he came out on the platform, and someone called out: `There he is, now!' and in a second such a cheer went up as you never heard. They crowded around the old fellow and shook hands with him and hugged him as if he had been a girl."

"I suppose you have reference to the time before you were married," interrupted someone, but Lesponts did not heed him. He went on:

"It seemed the rumor had got out that morning that it was the Captain's train that had gone off the track and that the Captain had been killed in the wreck, and this crowd had assembled to meet the body. `We were going to give you a big funeral, Captain,' said one old fellow; `they've got you while you are living, but we claim you when you are dead. We ain't going to let 'em have you then. We're going to put you to sleep in old Virginia.'

"The old fellow was much affected, and made them a little speech. He introduced us to them all. He said: `Gentlemen, these are my boys, my neighbors and family;' and then, `Boys, these are my friends; I don't know all their names yet, but they are my friends.' And we were. He rushed off to send a telegram to his wife in New Orleans, because, as he said afterwards, she, too, might get hold of the report that he had been killed; and a Christmas message would set her up, anyhow. She'd be a little low down at his not getting there, he said, as he had never missed a Christmas-day at home since '64.

"When dinner-time came he was invited in by pretty nearly everyone in the car, but he declined; he said he had to attend to a matter. I was going in with a party, but I thought the old fellow would be lonely, so I waited and insisted on his dining with me. I found that it had occurred to him that a bowl of eggnogg would make it seem more like Christmas, and he had telegraphed ahead to a friend at a little place to have `the materials' ready. Well, they were on hand when we got there, and we took them aboard, and the old fellow made one of the finest eggnoggs you ever tasted in your life. The rest of the passengers had no idea of what was going on, and when the old chap came in with a big bowl, wreathed in holly, borne by Nick, and the old Captain marching behind, there was quite a cheer. It was offered to the ladies first, of course, and then the men assembled in the smoker and the Captain did the honors. He did them handsomely, too: made us one of the prettiest little speeches you ever heard; said that Christmas was not dependent on the fireplace, however much a roaring fire might contribute to it; that it was in everyone's heart and might be enjoyed as well in a railway-car as in a hall, and that in this time of change and movement it behooved us all to try and keep up what was good and cheerful and bound us together, and to remember that Christmas was not only a time for merry-making, but was the time when the Saviour of the world came among men to bring peace and good-will, and that we should remember all our friends everywhere. `And, gentlemen,' he said, `there are two toasts I always like to propose at this time, and which I will ask you to drink. The first is to my wife.' It was drunk, you may believe. `And the second is, "My friends: all mankind."' This too, was drunk, and just then someone noticed that the old fellow had nothing but a little water in his glass. `Why, Captain,' he said, `you are not drinking! that is not fair.' `Well, no, sir,' said the old fellow, `I never drink anything on duty; you see it is one of the regulations and I subscribed them, and, of course, I could not break my word. Nick, there, will drink my share, however, when you are through; he isn't held up to quite such high accountability.' And sure enough, Nick drained off a glass and made a speech which got him a handful of quarters. Well, of course, the old Captain owned not only the car, but all in it by this time, and we spent one of the jolliest evenings you ever saw. The glum fellow who had insisted on his rights at Washington made a little speech, and paid the Captain one of the prettiest compliments I ever heard. He said he had discovered that the Captain had given him his own lower berth after he had been so rude to him, and that instead of taking his upper berth as he had supposed he would have done, he had given that to another person and had sat up himself all night. That was I. The old fellow had given the grumbler his `lower' in the smoking-room, and had given me his `upper'. The fellow made him a very handsome apology before us all, and the Captain had his own berth that night, you may believe.

"Well, we were all on the `qui vive' to see the Captain's wife when we got to New Orleans. The Captain had told us that she always came down to the station to meet him; so we were all on the lookout for her. He told me the first thing that he did was to kiss her, and then he went and filed his reports, and then they went home together, `And if you'll come and dine with me,' he said to me, `I'll give you the best dinner you ever had -- real old Virginia cooking; Nick's wife is our only servant, and she is an excellent cook.' I promised him to go one day, though I could not go the first day. Well, the meeting between the old fellow and his wife was worth the trip to New Orleans to see. I had formed a picture in my mind of a queenly looking woman, a Southern matron -- you know how you do? And when we drew into the station I looked around for her. As I did not see her, I watched the Captain. He got off, and I missed him in the crowd. Presently, though, I saw him and I asked him, `Captain, is she here?' `Yes, sir, she is, she never misses; that's the sort of a wife to have, sir; come here and let me introduce you.' He pulled me up and introduced me to a sweet little old lady, in an old, threadbare dress and wrap, and a little, faded bonnet, whom I had seen as we came up, watching eagerly for someone, but whom I had not thought of as being possibly the Captain's grand-dame. The Captain's manner, however, was beautiful. `My dear, this is my friend, Mr. Lesponts, and he has promised to come and dine with us,' he said, with the air of a lord, and then he leaned over and whispered something to her. `Why, she's coming to dine with us to-day,' she said with a very cheery laugh; and then she turned and gave me a look that swept me from top to toe, as if she were weighing me to see if I'd do. I seemed to pass, for she came forward and greeted me with a charming cordiality, and invited me to dine with them, saying that her husband had told her I knew Miss So-and-So, and she was coming that day, and if I had no other engagement they would be very glad if I would come that day, too. Then she turned to the Captain and said, `I saved Christmas dinner for you; for when you didn't come I knew the calendar and all the rest of the world were wrong; so to-day is our Christmas.'

-- "Well, that's all," said Lesponts; "I did not mean to talk so much, but the old Captain is such a character, I wish you could know him. You'd better believe I went, and I never had a nicer time. They were just as poor as they could be, in one way, but in another they were rich. He had a sweet little home in their three rooms. I found that my friend always dined with them one day in the Christmas-week, and I happened to hit that day." He leaned back.

"That was the beginning of my good fortune," he said, slowly, and then stopped. Most of the party knew Lesponts's charming wife, so no further explanation was needed. One of them said presently, however, "Lesponts, why didn't you fellows get him some better place?"

"He was offered a place," said Lesponts. "The fellow who had made the row about the lower berth turned out to be a great friend of the head of the Pullman Company, and he got him the offer of a place at three times the salary he got, but after consideration, he declined it. He would have had to come North, and he said that he could not do that: his wife's health was not very robust and he did not know how she could stand the cold climate; then, she had made her friends, and she was too old to try to make a new set; and finally, their little girl was buried there, and they did not want to leave her; so he declined. When she died, he said, or whichever one of them died first, the other would come back home to the old place in Virginia, and bring the other two with him, so they could all be at home together again. Meantime, they were very comfortable and well satisfied."

There was a pause after Lesponts ended, and then one of the fellows rang the bell and said, "Let's drink the old Captain's health," which was unanimously agreed to. Newton walked over to a table and wrote a note, and then slipped out of the club; and when next day I inquired after him of the boy at the door, he said he had left word to tell anyone who asked for him, that he would not be back till after Christmas; that he had gone home to Virginia. Several of the other fellows went off home too, myself among them, and I was glad I did, for I heard one of the men say he never knew the club so deserted as it was that Christmas-day.

How the Captain Made Christmas is a featured selection in our collection of Christmas Stories.