Chapter VII - Certain Workers The Future in America

I

Those Who Do Not Get

Let us now look a little at another aspect of this process of individualistic competition which is the economic process in America, and which is giving us on its upper side the spenders of Fifth Avenue, the slow accumulators of the Astor type, and the great getters of the giant business organizations, the Trusts and acquisitive finance. We have concluded that this process of free and open competition in business which, clearly, the framers of the American Constitution imagined to be immortal, does as a matter of fact tend to kill itself through the advantage property gives in the acquisition of more property. But before we can go on to estimate the further future of this process we must experiment with another question. What is happening to those who have not got and who are not getting wealth, who are, in fact, falling back in the competition?

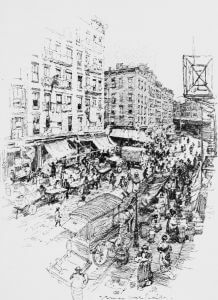

Now there can be little doubt to any one who goes to and fro in America that in spite of the huge accumulation of property in a few hands that is now in progress, there is still no general effect of impoverishment. To me, coming from London to New York, the effect of the crowd in the trolley-cars and subways and streets was one of exceptional prosperity. New York has no doubt its effects of noise, disorder, discomfort, and a sort of brutality, but to begin with one sees nothing of the underfed people, the numerous dingily clad and grayly housed people who catch the eye in London. Even in the congested arteries, the filthy back streets of the East Side I found myself saying, as a thing remarkable, "These people have money to spend." In London one travels long distances for two cents, and great regiments of people walk; in New York the universal fare is five cents and everybody rides. Common people are better gloved and better booted in America than in any European country I know, in spite of the higher prices for clothing here, the men wear ready-made suits, it is true, to a much greater extent, but they are newer and brighter than the London clerk's carefully brushed, tailor-made garments. Wages translated from dollars into shillings seem enormous.

Now there can be little doubt to any one who goes to and fro in America that in spite of the huge accumulation of property in a few hands that is now in progress, there is still no general effect of impoverishment. To me, coming from London to New York, the effect of the crowd in the trolley-cars and subways and streets was one of exceptional prosperity. New York has no doubt its effects of noise, disorder, discomfort, and a sort of brutality, but to begin with one sees nothing of the underfed people, the numerous dingily clad and grayly housed people who catch the eye in London. Even in the congested arteries, the filthy back streets of the East Side I found myself saying, as a thing remarkable, "These people have money to spend." In London one travels long distances for two cents, and great regiments of people walk; in New York the universal fare is five cents and everybody rides. Common people are better gloved and better booted in America than in any European country I know, in spite of the higher prices for clothing here, the men wear ready-made suits, it is true, to a much greater extent, but they are newer and brighter than the London clerk's carefully brushed, tailor-made garments. Wages translated from dollars into shillings seem enormous.

And there is no perceptible fall in wages going on. On the whole wages tend to rise. For almost all sorts of men, for working women who are not "refined," there is a limitless field of employment. The fact that a growing proportion of the wealth of the community is passing into the hands of a small minority of successful getters, is masked to superficial observation by the enormous increase of the total wealth. The growth process overrides the economic process and may continue to do so for many years.

So that the great mass of the population is not consciously defeated in the economic game. It is only failing to get a large share in the increment of wealth. The European reader must dismiss from his mind any conception of the general American population as a mass of people undergoing impoverishment through the enrichment of the few. He must substitute for that figure a mass of people, very busy, roughly prosperous, generally self-satisfied, but ever and again stirred to bouts of irascibility and suspicion, inundated by a constantly swelling flood of prosperity that pours through it and over it and passes by it, without changing or enriching it at all. Ever and again it is irritated by some rise in price, an advance in coal, for example, or meat or rent, that swallows up some anticipated gain, but that is an entirely different thing from want or distress, from the fireless hungering poverty of Europe.

Nevertheless, the sense of losing develops and spreads in the mass of the American people. Privations are not needed to create a sense of economic disadvantage; thwarted hopes suffice. The speed and pressure of work here is much greater than in[Pg 107] Europe, the impatience for realization intenser. The average American comes into life prepared to "get on," and ready to subordinate most things in life to that. He encounters a rising standard of living. He finds it more difficult to get on than his father did before him. He is perplexed and irritated by the spectacle of lavish spending and the report of gigantic accumulations that outshine his utmost possibilities of enjoyment or success. He is a busy and industrious man, greatly preoccupied by the struggle, but when he stops to think and talk at all, there can be little doubt that his outlook is a disillusioned one, more and more tinged with a deepening discontent.

II

The Little Messenger-boy

But the state of mind of the average American we have to consider later. That is the central problem of this horoscope we contemplate. Before we come to that we have to sketch out all the broad aspects of the situation with which that mind has to deal.

Now in the preceding chapter I tried to convey my impression of the spending and wealth-getting of this vast community; I tried to convey how irresponsible it was, how unpremeditated. The American rich have, as it were, floated up out of a confused struggle of equal individuals. That indi[Pg 108]vidualistic commercial struggle has not only flung up these rich to their own and the world's amazement, it is also, with an equal blindness, crushing and maiming great multitudes of souls. But this is a fact that does not smite upon one's attention at the outset. The English visitor to the great towns sees the spending, sees the general prosperity, the universal air of confident pride; he must go out of his way to find the under side to these things.

One little thing set me questioning. I had been one Sunday night down-town, supping and talking with Mr. Abraham Cahan about the "East Side," that strange city within a city which has a drama of its own and a literature and a press, and about Russia and her problem, and I was returning on the subway about two o'clock in the morning. I became aware of a little lad sitting opposite me, a childish-faced delicate little creature of eleven years old or so, wearing the uniform of a messenger-boy. He drooped with fatigue, roused himself with a start, edged off his seat with a sigh, stepped off the car, and was vanishing up-stairs into the electric glare of Astor Place as the train ran out of the station.

"What on earth," said I, "is that baby doing abroad at this time of night?"

For me this weary little wretch became the irritant centre of a painful region of inquiry. "How many hours a day may a child work in New York," I began to ask people, "and when may a boy leave school?"

I had blundered, I found, upon the weakest spot in America's fine front of national well-being. My eyes were opened to the childish newsboys who sold me papers, and the little bootblacks at the street corners. Nocturnal child employment is a social abomination. I gathered stories of juvenile vice, of lads of nine and ten suffering from terrible diseases, of the contingent sent by these messengers to the hospitals and jails. I began to realize another aspect of that great theory of the liberty of property and the subordination of the state to business, upon which American institutions are based. That theory has no regard for children. Indeed, it is a theory that disregards women and children, the cardinal facts of life altogether. They are private things....

It is curious how little we, who live in the dawning light of a new time, question the intellectual assumptions of the social order about us. We find ourselves in a life of huge confusions and many cruelties, we plan this and that to remedy and improve, but very few of us go down to the ideas that begot these ugly conditions, the laws, the usages and liberties that are now in their detailed expansion so perplexing, intricate, and overwhelming. Yet the life of man is altogether made up of will cast into the mould of ideas, and only by correcting ideas, changing ideas and replacing ideas are any ameliorations and advances to be achieved in human destiny. All other things are subordinate to that.

Now the theory of liberty upon which the liberalism of Great Britain, the Constitution of the United States, and the bourgeois Republic of France rests, assumes that all men are free and equal. They are all tacitly supposed to be adult and immortal, they are sovereign over their property and over their wives and children, and everything is framed with a view to insuring them security in the enjoyment of their rights. No doubt this was a better theory than that of the divine right of kings, against which it did triumphant battle, but it does, as one sees it to-day, fall most extraordinarily short of the truth, and only a few logical fanatics have ever tried to carry it out to its complete consequences. For example, it ignored the facts that more than half of the adult people in a country are women, and that all the men and women of a country taken together are hardly as numerous and far less important to the welfare of that country than the individuals under age. It regarded living as just living, a stupid dead level of egotistical effort and enjoyment; it was blind to the fact that living is part growing, part learning, part dying to make way and altogether service and sacrifice. It asserted that the care and education of children, and business bargains affecting the employment and welfare of women and children, are private affairs. It resisted the compulsory education of children and factory legislation, therefore, with extraordinary persistence and bitterness. The common[Pg 111]sense of the three great progressive nations concerned has been stronger than their theory, but to this day enormous social evils are to be traced to that passionate jealousy of state intervention between a man and his wife, his children, and other property, which is the distinctive unprecedented feature of the originally middle-class modern organization of society upon commercial and industrial conceptions in which we are all (and America most deeply) living.

I began with a drowsy little messenger-boy in the New York Subway. Before I had done with the question I had come upon amazing things. Just think of it! This richest, greatest country the world has ever seen has over 1,700,000 children under fifteen years of age toiling in fields, factories, mines, and workshops. And Robert Hunter—whose Poverty, if I were autocrat, should be compulsory reading for every prosperous adult in the United States, tells me of "not less than eighty thousand children, most of whom are little girls, at present employed in the textile mills of this country. In the South there are now six times as many children at work as there were twenty years ago. Child labor is increasing yearly in that section of the country. Each year more little ones are brought in from the fields and hills to live in the degrading atmosphere of the mill towns."...

Children are deliberately imported by the Italians. I gathered from Commissioner Watchorn at[Pg 112] Ellis Island that the proportion of little nephews and nieces, friends' sons, and so forth, brought in by them is peculiarly high, and I heard him try and condemn a doubtful case. It was a particularly unattractive Italian in charge of a dull-eyed little boy of no ascertainable relationship....

In the worst days of cotton-milling in England the conditions were hardly worse than those now existing in the South. Children, the tiniest and frailest, of five and six years of age, rise in the morning and, like old men and women, go to the mills to do their day's labor; and when they return home, "wearily fling themselves on their beds, too tired to take off their clothes." Many children work all night—"in the maddening racket of the machinery, in an atmosphere unsanitary and clouded with humidity and lint."

"It will be long," adds Mr. Hunter, in his description, "before I forget the face of a little boy of six years, with his hands stretched forward to rearrange a bit of machinery, his pallid face and spare form already showing the physical effects of labor. This child, six years of age, was working twelve hours a day."

From Mr. Spargo's Bitter Cry of the Children I learn this much of the joys of certain among the youth of Pennsylvania:

"For ten or eleven hours a day children of ten and eleven stoop over the chute and pick out the slate and other impurities from the coal as it moves past them.[Pg 113] The air is black with coal-dust, and the roar of the crushers, screens, and rushing mill-race of coal is deafening. Sometimes one of the children falls into the machinery and is terribly mangled, or slips into the chute and is smothered to death. Many children are killed in this way. Many others, after a time, contract coal-miners' asthma and consumption, which gradually undermine their health. Breathing continually day after day the clouds of coal-dust, their lungs become black and choked with small particles of anthracite."...

In Massachusetts, at Fall River, the Hon. J.F. Carey tells us how little naked boys, free Americans, work for Mr. Borden, the New York millionaire, packing cloth into bleaching vats in a bath of chemicals that bleaches their little bodies like the bodies of lepers....

Well, we English have no right to condemn the Americans for these things. The history of our own industrial development is black with the blood of tortured and murdered children. America still has the factory serfs. New Jersey sends her pauper children south to-day into worse than slavery, but, as Cottle tells in his reminiscences of Southey and Coleridge, that is precisely the same wretched export Bristol packed off to feed the mills of Manchester in late Georgian times. We got ahead with factory legislation by no peculiar virtue in our statecraft, it was just the revenge the landlords took upon the manufacturers for reform and free trade in corn and food. In America the manufacturers have had things to themselves.

And America has difficulties to encounter of which we know nothing. In the matter of labor legislation each State legislature is supreme; in each separate State the forces of light and progress must fight the battle of the children and the future over again against interests, lies, prejudice and stupidity. Each State pleads the bad example of another State, and there is always the threat that capital will withdraw. No national minimum is possible under existing conditions. And when the laws have passed there is still the universal contempt for State control to reckon with, the impossibilities of enforcement. Illinois, for instance, scandalized at the spectacle of children in those filthy stock-yards, ankle-deep in blood, cleaning intestines and trimming meat, recently passed a child-labor law that raised the minimum age for such employment to sixteen, but evasion, they told me in Chicago, was simple and easy. New York, too, can show by its statute-books that my drowsy nocturnal messenger-boy was illegal and impossible....

This is the bottomest end of the scale that at the top has all the lavish spending of Fifth Avenue, the joyous wanton giving of Mr. Andrew Carnegie. Equally with these things it is an unpremeditated consequence of an inadequate theory of freedom. The foolish extravagances of the rich, the architectural pathos of Newport, the dingy, noisy, economic jumble of central and south Chicago, the[Pg 115] Standard Oil offices in Broadway, the darkened streets beneath New York's elevated railroad, the littered ugliness of Niagara's banks, and the lower-most hell of child suffering are all so many accordant aspects and inexorable consequences of the same undisciplined way of living. Let each man push for himself—it comes to these things....

So far as our purpose of casting a horoscope goes we have particularly to note this as affecting the future; these working children cannot be learning to read—though they will presently be having votes—they cannot grow up fit to bear arms, to be in any sense but a vile computing sweater's sense, men. So miserably they will avenge themselves by supplying the stuff for vice, for crime, for yet more criminal and political manipulations. One million seven hundred children, practically uneducated, are toiling over here, and growing up, darkened, marred, and dangerous, into the American future I am seeking to forecast.