Akin to Love

by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Akin to Love (1909) is a gently comic romance about two middle-aged neighbors on the verge of something more than friendship, set against the crisp beauty of a Canadian winter afternoon. "Outside, in the clear crispness of a Canadian winter, the long blue shadows from the tall firs were falling over the snow."

David Hartley had dropped in to pay a neighbourly call on Josephine Elliott. It was well along in the afternoon, and outside, in the clear crispness of a Canadian winter, the long blue shadows from the tall firs behind the house were falling over the snow.

It was a frosty day, and all the windows of every room where there was no fire were covered with silver palms. But the big, bright kitchen was warm and cosy, and somehow seemed to David more tempting than ever before, and that is saying a good deal. He had an uneasy feeling that he had stayed long enough and ought to go. Josephine was knitting at a long gray sock with doubly aggressive energy, and that was a sign that she was talked out. As long as Josephine had plenty to say, her plump white fingers, where her mother's wedding ring was lost in dimples, moved slowly among her needles. When conversation flagged she fell to her work as furiously as if a husband and half a dozen sons were waiting for its completion. David often wondered in his secret soul what Josephine did with all the interminable gray socks she knitted. Sometimes he concluded that she put them in the home missionary barrels; again, that she sold them to her hired man. At any rate, they were very warm and comfortable looking, and David sighed as he thought of the deplorable state his own socks were generally in.

When David sighed Josephine took alarm. She was afraid David was going to have one of his attacks of foolishness. She must head him off someway, so she rolled up the gray sock, stabbed the big pudgy ball with her needles, and said she guessed she'd get the tea.

David got up.

"Now, you're not going before tea?" said Josephine hospitably. "I'll have it all ready in no time."

"I ought to go home, I s'pose," said David, with the air and tone of a man dallying with a great temptation. "Zillah'll be waiting tea for me; and there's the stock to tend to."

"I guess Zillah won't wait long," said Josephine. She did not intend it at all, but there was a certain scornful ring in her voice. "You must stay. I've a fancy for company to tea."

David sat down again. He looked so pleased that Josephine went down on her knees behind the stove, ostensibly to get a stick of firewood, but really to hide her smile.

"I suppose he's tickled to death to think of getting a good square meal, after the starvation rations Zillah puts him on," she thought.

But Josephine misjudged David just as much as he misjudged her. She had really asked him to stay to tea out of pity, but David thought it was because she was lonesome, and he hailed that as an encouraging sign. And he was not thinking about getting a good meal either, although his dinner had been such a one as only Zillah Hartley could get up. As he leaned back in his cushioned chair and watched Josephine bustling about the kitchen, he was glorying in the fact that he could spend another hour with her, and sit opposite to her at the table while she poured his tea for him and passed him the biscuits, just as if—just as if—

Here Josephine looked straight at him with such intent and stern brown eyes that David felt she must have read his thoughts, and he colored guiltily. But Josephine did not even notice that he was blushing. She had only paused to wonder whether she would bring out cherry or strawberry preserve; and, having decided on the cherry, took her piercing gaze from David without having seen him at all. But he allowed his thoughts no more vagaries.

Josephine set the table with her mother's wedding china. She used it because it was the anniversary of her mother's wedding day, but David thought it was out of compliment to him. And, as he knew quite well that Josephine prized that china beyond all her other earthly possessions, he stroked his smooth-shaven, dimpled chin with the air of a man to whom is offered a very subtly sweet homage.

Josephine whisked in and out of the pantry, and up and down cellar, and with every whisk a new dainty was added to the table. Josephine, as everybody in Meadowby admitted, was past mistress in the noble art of cookery. Once upon a time rash matrons and ambitious young wives had aspired to rival her, but they had long ago realised the vanity of such efforts and dropped comfortably back to second place.

Josephine felt an artist's pride in her table when she set the teapot on its stand and invited David to sit in. There were pink slices of cold tongue, and crisp green pickles and spiced gooseberry, the recipe for which Josephine had invented herself, and which had taken first prize at the Provincial Exhibition for six successive years; there was a lemon pie which was a symphony in gold and silver, biscuits as light and white as snow, and moist, plummy cubes of fruit cake. There was the ruby-tinted cherry preserve, a mound of amber jelly, and, to crown all, steaming cups of tea, in flavour and fragrance unequalled.

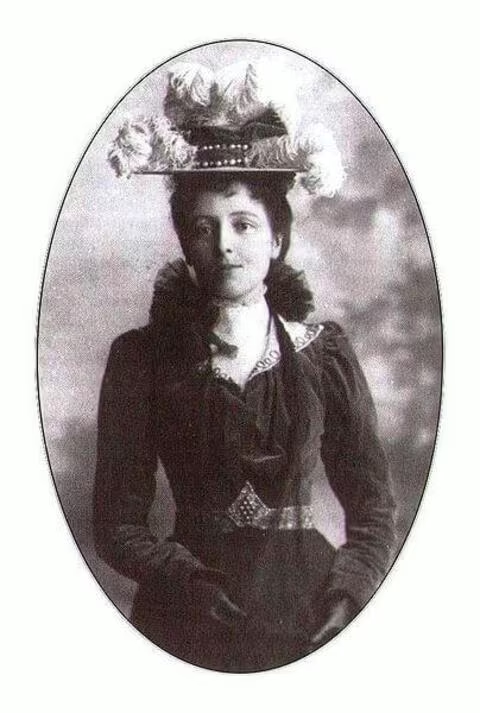

And Josephine, too, sitting at the head of the table, with her smooth, glossy crimps of black hair and cheeks as rosy clear as they had been twenty years ago, when she had been a slender slip of girlhood and bashful young David Hartley had looked at her over his hymn-book in prayer-meeting and tramped all the way home a few feet behind her, because he was too shy to go boldly up and ask if he might see her home.

All taken together, what wonder if David lost his head over that tea-table and determined to ask Josephine the same old question once more? It was eighteen years since he had asked it for the first time, and two years since the last. He would try his luck again; Josephine was certainly more gracious than he remembered her to ever have been before.

When the meal was over Josephine cleared the table and washed the dishes. When she had taken a dry towel and sat down by the window to polish her china David understood that his opportunity had come. He moved over and sat down beside her on the sofa by the window.

Outside the sun was setting in a magnificent arch of light and colour over the snow-clad hills and deep blue St. Lawrence gulf. David grasped at the sunset as an introductory factor.

"Isn't that fine, Josephine?" he said admiringly. "It makes me think of that piece of poetry that used to be in the old Fifth Reader when we went to school. D'ye mind how the teacher used to drill us up in it on Friday afternoons? It begun

'Slow sinks more lovely ere his race is run Along Morea's hills the setting sun.'"

Then David declaimed the whole passage in a sing-song tone, accompanied by a few crude gestures recalled from long-ago school-boy elocution. Josephine knew what was coming. Every time David proposed to her he had begun by reciting poetry. She twirled her towel around the last plate resignedly. If it had to come, the sooner it was over the better. Josephine knew by experience that there was no heading David off, despite his shyness, when he had once got along as far as the poetry.

"But it's going to be for the last time," she said determinedly. "I'm going to settle this question so decidedly to-night that there'll never be a repetition."

When David had finished his quotation he laid his hand on Josephine's plump arm.

"Josephine," he said huskily, "I s'pose you couldn't—could you now?—make up your mind to have me. I wish you would, Josephine—I wish you would. Don't you think you could, Josephine?"

Josephine folded up her towel, crossed her hands on it, and looked her wooer squarely in the eyes.

"David Hartley," she said deliberately, "what makes you go on asking me to marry you every once in a while when I've told you times out of mind that I can't and won't?"

"Because I can't help hoping that you'll change your mind through time," David replied meekly.

"Well, you just listen to me. I will not marry you. That is in the first place. And in the second, this is to be final. It has to be. You are never to ask me this again under any circumstances. If you do I will not answer you—I will not let on I hear you at all; but (and Josephine spoke very slowly and impressively) I will never speak to you again—never. We are good friends now, and I like you real well, and like to have you drop in for a neighbourly chat as often as you wish to, but there'll be an end, short and sudden, to that, if you don't mind what I say."

"Oh, Josephine, ain't that rather hard?" protested David feebly. It seemed terrible to be cut off from all hope with such finality as this.

"I mean every word of it," returned Josephine calmly. "You'd better go home now, David. I always feel as if I'd like to be alone for a spell after a disagreeable experience."

David obeyed sadly and put on his cap and overcoat. Josephine kindly warned him not to slip and break his legs on the porch, because the floor was as icy as anything; and she even lighted a candle and held it up at the kitchen door to guide him safely out. David, as he trudged sorrowfully homeward across the fields, carried with him the mental picture of a plump, sonsy woman, in a trim dress of plum-coloured homespun and ruffled blue-check apron, haloed by candlelight. It was not a very romantic vision, perhaps, but to David it was more beautiful than anything else in the world.

When David was gone Josephine shut the door with a little shiver. She blew out the candle, for it was not yet dark enough to justify artificial light to her thrifty mind. She thought the big, empty house, in which she was the only living thing, was very lonely. It was so still, except for the slow tick of the "grandfather's clock" and the soft purr and crackle of the wood in the stove. Josephine sat down by the window.

"I wish some of the Sentners would run down," she said aloud. "If David hadn't been so ridiculous I'd have got him to stay the evening. He can be good company when he likes—he's real well-read and intelligent. And he must have dismal times at home there with nobody but Zillah."

She looked across the yard to the little house at the other side of it, where her French-Canadian hired man lived, and watched the purple spiral of smoke from its chimney curling up against the crocus sky. Would she run over and see Mrs. Leon Poirier and her little black-eyed, brown-skinned baby? No, they never knew what to say to each other.

"If 'twasn't so cold I'd go up and see Ida," she said. "As it is, I guess I'd better fall back on my knitting, for I saw Jimmy Sentner's toes sticking through his socks the other day. How setback poor David did look, to be sure! But I think I've settled that marrying notion of his once for all and I'm glad of it."

She said the same thing next day to Mrs. Tom Sentner, who had come down to help her pick her geese. They were at work in the kitchen with a big tubful of feathers between them, and on the table a row of dead birds, which Leon had killed and brought in. Josephine was enveloped in a shapeless print wrapper, and had an apron tied tightly around her head to keep the down out of her beautiful hair, of which she was rather proud.

"What do you think, Ida?" she said, with a hearty laugh at the recollection. "David Hartley was here to tea last night, and asked me to marry him again. There's a persistent man for you. I can't brag of ever having had many beaux, but I've certainly had my fair share of proposals."

Mrs. Tom did not laugh. Her thin little face, with its faded prettiness, looked as if she never laughed.

"Why won't you marry him?" she said fretfully.

"Why should I?" retorted Josephine. "Tell me that, Ida Sentner."

"Because it is high time you were married," said Mrs. Tom decisively. "I don't believe in women living single. And I don't see what better you can do than take David Hartley."

Josephine looked at her sister with the interested expression of a person who is trying to understand some mental attitude in another which is a standing puzzle to her. Ida's evident wish to see her married always amused Josephine. Ida had married very young and for fifteen years her life had been one of drudgery and ill-health. Tom Sentner was a lazy, shiftless fellow. He neglected his family and was drunk half his time. Meadowby people said that he beat his wife when "on the spree," but Josephine did not believe that, because she did not think that Ida could keep from telling her if it were so. Ida Sentner was not given to bearing her trials in silence.

Had it not been for Josephine's assistance, Tom Sentner's family would have stood an excellent chance of starvation. Josephine practically kept them, and her generosity never failed or stinted. She fed and clothed her nephews and nieces, and all the gray socks whose destination puzzled David so much went to the Sentners.

As for Josephine herself, she had a good farm, a comfortable house, a plump bank account, and was an independent, unworried woman. And yet, in the face of all this, Mrs. Tom Sentner could bewail the fact that Josephine had no husband to look out for her. Josephine shrugged her shoulders and gave up the conundrum, merely saying ironically, in reply to her sister's remark:

"And go to live with Zillah Hartley?"

"You know very well you wouldn't have to do that. Ever since John Hartley's wife at the Creek died he's been wanting Zillah to go and keep house for him, and if David got married Zillah'd go quick. Catch her staying there if you were mistress! And David has such a beautiful house! It's ten times finer than yours, though I don't deny yours is comfortable. And his farm is the best in Meadowby and joins yours. Think what a beautiful property they'd make together. You're all right now, Josephine, but what will you do when you get old and have nobody to take care of you? I declare the thought worries me at night till I can't sleep."

"I should have thought you had enough worries of your own to keep you awake at nights without taking over any of mine," said Josephine drily. "As for old age, it's a good ways off for me yet. When your Jack gets old enough to have some sense he can come here and live with me. But I'm not going to marry David Hartley, you can depend on that, Ida, my dear. I wish you could have heard him rhyming off that poetry last night. It doesn't seem to matter much what piece he recites—first thing that comes into his head, I reckon. I remember one time he went clean through that hymn beginning, 'Hark from the tombs a doleful sound,' and two years ago it was 'To Mary in Heaven,' as lackadaisical as you please. I never had such a time to keep from laughing, but I managed it, for I wouldn't hurt his feelings for the world. No, I haven't any intention of marrying anybody, but if I had it wouldn't be dear old sentimental, easy-going David."

Mrs. Tom thumped a plucked goose down on the bench with an expression which said that she, for one, wasn't going to waste any more words on an idiot. Easy-going, indeed! Did Josephine consider that a drawback? Mrs. Tom sighed. If Josephine, she thought, had put up with Tom Sentner's tempers for fifteen years she would know how to appreciate a good-natured man at his real value.

The cold snap which had set in on the day of David's call lasted and deepened for a week. On Saturday evening, when Mrs. Tom came down for a jug of cream, the mercury of the little thermometer thumping against Josephine's porch was below zero. The gulf was no longer blue, but white with ice. Everything outdoors was crackling and snapping. Inside Josephine had kept roaring fires all through the house but the only place really warm was the kitchen.

"Wrap your head up well, Ida," she said anxiously, when Mrs. Tom rose to go. "You've got a bad cold."

"There's a cold going," said Mrs. Tom. "Everyone has it. David Hartley was up at our place to-day barking terrible—a real churchyard cough, as I told him. He never takes any care of himself. He said Zillah had a bad cold, too. Won't she be cranky while it lasts?"

Josephine sat up late that night to keep fires on. She finally went to bed in the little room opposite the big hall stove, and she slept at once, and dreamed that the thumps of the thermometer flapping in the wind against the wall outside grew louder and more insistent until they woke her up. Some one was pounding on the porch door.

Josephine sprang out of bed and hurried on her wrapper and felt shoes. She had no doubt that some of the Sentners were sick. They had a habit of getting sick about that time of night. She hurried out and opened the door, expecting to see hulking Tom Sentner, or perhaps Ida herself, big-eyed and hysterical.

But David Hartley stood there, panting for breath. The clear moonlight showed that he had no overcoat on, and he was coughing hard. Josephine, before she spoke a word, clutched him by the arm and pulled him in out of the wind.

"For pity's sake, David Hartley, what is the matter?"

"Zillah's awful sick," he gasped. "I came here because 'twas nearest. Oh, won't you come over, Josephine? I've got to go for the doctor and I can't leave her alone. She's suffering dreadful. I know you and her ain't on good terms, but you'll come, won't you?"

"Of course I will," said Josephine sharply. "I'm not a barbarian, I hope, to refuse to go to the help of a sick person, if 'twas my worst enemy. I'll go in and get ready and you go straight to the hall stove and warm yourself. There's a good fire in it yet. What on earth do you mean, starting out on a bitter night like this without an overcoat or even mittens, and you with a cold like that?"

"I never thought of them, I was so frightened," said David apologetically. "I just lit up a fire in the kitchen stove as quick's I could and run. It rattled me to hear Zillah moaning so's you could hear her all over the house."

"You need someone to look after you as bad as Zillah does," said Josephine severely.

In a very few minutes she was ready, with a basket packed full of homely remedies, "for like as not there'll be no putting one's hand on anything there," she muttered. She insisted on wrapping her big plaid shawl around David's head and neck, and made him put on a pair of mittens she had knitted for Jack Sentner. Then she locked the door and they started across the gleaming, crusted field. It was so slippery that Josephine had to cling to David's arm to keep her feet. In the rapture of supporting her David almost forgot everything else.

In a few minutes they had passed under the bare, glistening boughs of the poplars on David's lawn, and for the first time Josephine crossed the threshold of David Hartley's house.

Years ago, in her girlhood, when the Hartley's lived in the old house and there were half a dozen girls at home, Josephine had frequently visited there. All the Hartley girls liked her except Zillah. She and Zillah never "got on" together. When the other girls had married and gone, Josephine gave up visiting there. She had never been inside the new house, and she and Zillah had not spoken to each other for years.

Zillah was a sick woman—too sick to be anything but civil to Josephine. David started at once for the doctor at the Creek, and Josephine saw that he was well wrapped up before she let him go. Then she mixed up a mustard plaster for Zillah and sat down by the bedside to wait.

When Mrs. Tom Sentner came down the next day she found Josephine busy making flaxseed poultices, with her lips set in a line that betokened she had made up her mind to some disagreeable course of duty.

"Zillah has got pneumonia bad," she said, in reply to Mrs. Tom's inquiries. "The Doctor is here and Mary Bell from the Creek. She'll wait on Zillah, but there'll have to be another woman here to see to the work. I reckon I'll stay. I suppose it's my duty and I don't see who else could be got. You can send Mamie and Jack down to stay at my house until I can go back. I'll run over every day and keep an eye on things."

At the end of a week Zillah was out of danger. Saturday afternoon Josephine went over home to see how Mamie and Jack were getting on. She found Mrs. Tom there, and the latter promptly despatched Jack and Mamie to the post-office that she might have an opportunity to hear Josephine's news.

"I've had an awful week of it, Ida," said Josephine solemnly, as she sat down by the stove and put her feet up on the glowing hearth.

"I suppose Zillah is pretty cranky to wait on," said Mrs. Tom sympathetically.

"Oh, it isn't Zillah. Mary Bell looks after her. No, it's the house. I never lived in such a place of dust and disorder in my born days. I'm sorrier for David Hartley than I ever was for anyone before."

"I suppose he's used to it," said Mrs. Tom with a shrug.

"I don't see how anyone could ever get used to it," groaned Josephine. "And David used to be so particular when he was a boy. The minute I went there the other night I took in that kitchen with a look. I don't believe the paint has even been washed since the house was built. I honestly don't. And I wouldn't like to be called upon to swear when the floor was scrubbed either. The corners were just full of rolls of dust—you could have shovelled it out. I swept it out next day and I thought I'd be choked. As for the pantry—well, the less said about that the better. And it's the same all through the house. You could write your name on everything. I couldn't so much as clean up. Zillah was so sick there couldn't be a bit of noise made. I did manage to sweep and dust, and I cleaned out the pantry. And, of course, I saw that the meals were nice and well cooked. You should have seen David's face. He looked as if he couldn't get used to having things clean and tasty. I darned his socks—he hadn't a whole pair to his name—and I've done everything I could to give him a little comfort. Not that I could do much. If Zillah heard me moving round she'd send Mary Bell out to ask what the matter was. When I wanted to go upstairs I'd have to take off my shoes and tiptoe up on my stocking feet, so's she wouldn't know it. And I'll have to stay there another fortnight yet. Zillah won't be able to sit up till then. I don't really know if I can stand it without falling to and scrubbing the house from garret to cellar in spite of her."

Mrs. Tom Sentner did not say much to Josephine. To herself she said complacently:

"She's sorry for David. Well, I've always heard that pity was akin to love. We'll see what comes of this."

Josephine did manage to live through that fortnight. One morning she remarked to David at the breakfast table:

"Well, I think that Mary Bell will be able to attend to the work after today, David. I guess I'll go home tonight."

David's face clouded over.

"Well, I s'pose we oughtn't to keep you any longer, Josephine. I'm sure it's been awful good of you to stay this long. I don't know what we'd have done without you."

"You're welcome," said Josephine shortly.

"Don't go for to walk home," said David; "the snow is too deep. I'll drive you over when you want to go."

"I'll not go before the evening," said Josephine slowly.

David went out to his work gloomily. For three weeks he had been living in comfort. His wants were carefully attended to; his meals were well cooked and served, and everything was bright and clean. And more than all, Josephine had been there, with her cheerful smile and companionable ways. Well, it was all ended now.

Josephine sat at the breakfast table long after David had gone out. She scowled at the sugar-bowl and shook her head savagely at the tea-pot.

"I'll have to do it," she said at last.

"I'm so sorry for him that I can't do anything else."

She got up and went to the window, looking across the snowy field to her own home, nestled between the grove of firs and the orchard.

"It's awful snug and comfortable," she said regretfully, "and I've always felt set on being free and independent. But it's no use. I'd never have a minute's peace of mind again, thinking of David living here in dirt and disorder, and him so particular and tidy by nature. No, it's my duty, plain and clear, to come here and make things pleasant for him—the pointing of Providence, as you might say. The worst of it is, I'll have to tell him so myself. He'll never dare to mention the subject again, after what I said to him that night he proposed last. I wish I hadn't been so dreadful emphatic. Now I've got to say it myself if it is ever said. But I'll not begin by quoting poetry, that's one thing sure!"

Josephine threw back her head, crowned with its shining braids of jet-black hair, and laughed heartily. She bustled back to the stove and poked up the fire.

"I'll have a bit of corned beef and cabbage for dinner," she said, "and I'll make David that pudding he's so fond of. After all, it's kind of nice to have someone to plan and think for. It always did seem like a waste of energy to fuss over cooking things when there was nobody but myself to eat them."

Josephine sang over her work all day, and David went about his with the face of a man who is going to the gallows without benefit of clergy. When he came in to supper at sunset his expression was so woe-begone that Josephine had to dodge into the pantry to keep from laughing outright. She relieved her feelings by pounding the dresser with the potato masher, and then went primly out and took her place at the table.

The meal was not a success from a social point of view. Josephine was nervous and David glum. Mary Bell gobbled down her food with her usual haste, and then went away to carry Zillah hers. Then David said reluctantly:

"If you want to go home now, Josephine, I'll hitch up Red Rob and drive you over."

Josephine began to plait the tablecloth. She wished again that she had not been so emphatic on the occasion of his last proposal. Without replying to David's suggestion she said crossly (Josephine always spoke crossly when she was especially in earnest):

"I want to tell you what I think about Zillah. She's getting better, but she's had a terrible shaking up, and it's my opinion that she won't be good for much all winter. She won't be able to do any hard work, that's certain. If you want my advice, I tell you fair and square that I think she'd better go off for a visit as soon as she's fit. She thinks so herself. Clementine wants her to go and stay a spell with her in town. 'Twould be just the thing for her."

"She can go if she wants to, of course," said David dully. "I can get along by myself for a spell."

"There's no need of your getting along by yourself," said Josephine, more crossly than ever. "I'll—I'll come here and keep house for you if you like."

David looked at her uncomprehendingly.

"Wouldn't people kind of gossip?" he asked hesitatingly. "Not but what—"

"I don't see what they'd have to gossip about," broke in Josephine, "if we were—married."

David sprang to his feet with such haste that he almost upset the table.

"Josephine, do you mean that?" he exclaimed.

"Of course I mean it," she said, in a perfectly savage tone. "Now, for pity's sake, don't say another word about it just now. I can't discuss it for a spell. Go out to your work. I want to be alone for awhile."

For the first and last time David disobeyed her. Instead of going out, he strode around the table, caught Josephine masterfully in his arms, and kissed her. And Josephine, after a second's hesitation, kissed him in return.