The Psychophonic Nurse

by David H. Keller

The Psychophonic Nurse (1928) is a prescient story about a mechanical nursemaid built to free a mother from childcare — a concept that anticipated modern debates about technology and parenting. "And that was the end of the Psychophonic Nurse."

”I AM mad! Just plain mad!”

”Well, it cannot be helped now,” replied the woman’s husband. “I am just as sorry as you are about it, but the baby is here now and some one has to take care of it.”

”I know all that,” said Susanna Teeple. “I want her to be well cared for, but I have my work to do and I have a real chance now to make a good income writing regularly for the Business Woman’s Advisor. I can easily make a thousand dollars a month if I can only find the time to do the work. I simply cannot do my work and care for the baby also. It was all a great mistake, having the baby now.”

“But I make enough to hire a nurse,” insisted the husband.

“Certainly, but where can I find one? The women who need the money are all working at seven hours a day and all the good nurses are in hospitals. I have searched all over town and they just laugh at me when I start talking to them.”

“Take care of her yourself. Systematize the work. Make a budget of your time, and a definite daily programme. Would you like me to employ an efficiency engineer? I have just had a man working along those lines in my factory. Bet he could help you a lot. Investigate the modern electrical machinery for taking care of the baby. Write down your troubles and my inventor will start working on them.”

“You talk just like a man!” replied the woman in cold anger. “Your suggestions show that you have no idea whatever of the problem of taking care of a three-weeks-old baby. I have used all the brains I have, and it takes me exactly seven hours a day. If the seven hours would all come at one time, I could spare them, but during the last three days, since I have kept count, I have been interrupted from my writing exactly one hundred and ten times every twenty-four hours and only about five per cent of those interruptions could have been avoided. The baby has to be fed and changed and washed and the bottles have to be sterilized and the crib fixed and the nursery cleaned, and just when I have her all right she regurgitates and then everything has to be done all over again. I just wish you had to take care of her for twenty-four hours, then you would know more than you do now. I have tried some of those electrical machines you speak of : had them on approval, but they were not satisfactory. The vacuum evaporator clogged up with talcum powder and the curd evacuator worked all right so long as it was over the mouth, but once the baby turned her head and the machine nearly pulled her ear off, before I found out why she was crying so. It would be wonderful if a baby could be taken care of by machinery, but I am afraid it will never be possible.”

“I believe it will,” said the husband. “Of course, even if the machine worked perfectly, it could not supply a mother’s love.”

“That idea of mother-love belongs to the dark ages,” sneered the disappointed woman. “We know now that a child does not know what love is till it develops the ability to think. Women have been deceiving themselves. They believed their babies loved them because they wanted to think so. When my child is old enough to know what love is, I will be properly demonstrative and not before. I have read very carefully what Hug-Hellmuth has written about the psychology of the baby and no child of mine is going to develop unhealthy complexes because I indulged it in untimely love and unnecessary caresses. I notice that you have kissed it when you thought I was not watching. How would you feel if, because of those kisses, your daughter developed an Edipus Complex when she reached the age of maturity? I am going to differ with you in regard to the machine; it will never be possible to care for a baby by means of machinery!”

“I believe it will!” insisted the man.

That evening he took the air-express for New York City, and when he returned, after some days absence, he was very uncommunicative in regard to the trip and what he had accomplished. Mrs. Teeple continued to take very good care of her baby, and also lost no opportunity of letting her husband realize what a sacrifice she was making for her family. The husband continued to preserve a dignified silence. Then, about two weeks after his New York trip, he sent his wife out for the afternoon and said that he would stay home and be nurse, just to see how it would go. After giving a thousand detailed instructions, the fond mother left for the party.

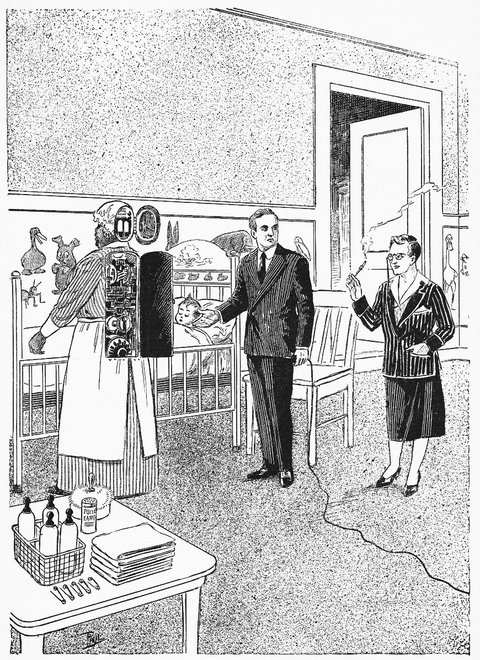

On her return, she found her husband calmly reading in the library. Going to the nursery, she found the baby asleep and by the side of the crib she saw a fat, black woman, clad in the spotless dress of a graduate nurse. She seemed to be as fast asleep as the child. Surprised, Mrs. Teeple walked to her husband’s chair.

“Well, what does this mean?” she demanded.

“That, my dear, is our new nurse.”

“Where did you get her?”

“I bought her in New York. In fact, I had her made to order.”

“You what?” asked the astonished woman.

“I had her made to order by the Eastinghouse Electric Company. You see, she is just a machine nurse, but as she does not eat anything, is on duty twenty-four hours a day and draws no salary, she is cheap at the price I paid for her.”

“Are you insane, or am I?”

“Neither. Certainly not your husband. Let me show you how she works. She is made of a combination of springs, levers, acoustic instruments, and by means of tubes such as are used in the radio, she is very sensitive to sounds. She is connected to the house lighting current by a long, flexible cord, which supplies her with the necessary energy. To simplify matters, I had the orders put into numbers instead of sentences. One means that the baby is to be fed; seven that she is to be changed. Twelve that it is time for a bath. I have a map made showing the exact position of the baby, the pile of clean diapers, the full bottles of milk, the clean sheets, in fact, everything needed to care for the baby during the twenty-four hours. In the morning, all you have to do is to see that everything needed is in its place. At six a.m. you go into the nursery and say one in a loud, clear voice. The nurse reaches over to the row of bottles, picks up one and puts the nipple in the baby’s mouth. At the end of ten minutes it takes the empty bottle and puts it back in the row. At six-thirty, you say clearly and distinctly, seven. The nurse removes the wet diaper, takes a can of talcum, uses it, puts it back, takes a diaper and pins it on the baby. Then she sits down.”

”I think that you are drunk!” said the woman, coolly.

“Not at all. You feel of her and see. She is just a lot of rods and wires and machinery. I had her padded and a face put on, because I thought she would look more natural that way.”

“Suppose all that you say is true. How can that help me. I have to see what the baby needs and then I have to look through the book and see what number to say and then I suppose I have to stay and watch the old thing work. I wanted a chance to work at my books and this — why, it is ridiculous!”

Her husband laughed at her.

”You are a nice little woman, Susanna, but you certainly lack imagination. When I ordered this machine, I thought about all that and so I bought a phonograph with a clock attachment. It will run for twenty-four hours without attention. Then I had a baby doctor work out a twenty-four hour programme of baby activity for different ages. Our baby is about two months old. You put this phonograph in the nursery with the two-month record on it. At six in the morning you see that all the supplies for that day are in the proper place; you see that the Psychophonic Nurse is in her proper place; the baby must be in her proper place. Then you attach the electric current to the phonograph and to the nurse and start the record. At definite periods of the twenty-four hours the phonograph will call out a number and then the nurse will do what is necessary for that hour. It will feed the baby so often and change it so often and bathe it so often. You start it at six and leave it alone till six the next morning.”

“That sounds fine,” said the wife, sarcastically, but suppose the baby gets wet between times? Suppose it starts to cry?”

“I thought of that, too. In every diaper is a fine copper wire. When that becomes wet a delicate current is sent — you understand I mean an electrical current, not a watery one — this current goes to an amplifier and a certain sound is made, and the nurse will properly react to that sound. We have also provided for crying. When the baby does that, the nurse will pick the little one up and rock her to sleep.”

“But the books say that to do that spoils the baby!”

“I know. I thought of that. But then the poor little thing has to have some love and affection in her life and so I thought it would not harm it any to be rocked now and then. That was one reason why I had the padding made the way that I did. I bet it will be mighty comfortable-like for the child. Then again, you know I had a black Mammy and I wanted my child to have one, too.”

“Well,” said the woman, rather petulantly, “show me how the thing works. I have a lot of writing to do and unless I do it, they will employ some one else.”

After two hours of close observation, she had to admit that the Nurse was just as capable of mechanically looking after the needs of a baby as she was. In fact, the cleverness of the performance made her gasp with astonishment. After each series of complicated acts, the machine went back to the chair and sat down.

The husband was triumphant.

“She does the work nicely,” he said. “Naturally, there is no intelligence, but none is needed in the early months of child-care.”

The Psychophonic Nurse performed her duties in a way that would have been a credit to any woman. Of course there were times when things did not go as well as they should, but the fault was always with the human side of the arrangement and not with the mechanical. Usually the mother was to blame because she did not place the supply of food or clothes in exactly the right place and once a new servant played havoc by cleaning the room and putting the nurse and the chair on the wrong side of the crib. Still, with a little supervision and care, things went very well indeed, and in a very short time the baby became accustomed to her black Mammy and the Mother was satisfied to spend a few minutes every morning arranging supplies and then leave the two of them alone for the rest of the twenty-four hours. Every two weeks a new record was placed in the phonograph, for it was determined that it was necessary to make a change in the programme at least that often.

Mrs. Teeple, thoroughly happy with her new freedom, now devoted her entire time to literature. Her articles, which appeared in the Saturday issue of The Business Woman’s Advisor, were more than brilliant and aroused the most favorable comment from all parts of the world. An English firm asked her to write a book on “Woman, the Conqueror,” and so relieved was she of household worries, that she started at once to pound out the introduction on her noiseless, electrical typewriter. Once in a while she felt the need of exercise and would stroll around the house, and occasionally look into the nursery. Now and then she would pick the little one up. As the child grew older, this made her cry, so the Mother decided that it was best not to interfere with the daily routine.

In spite of their efforts to conceal the activity of their new assistant, the news spread through the little town. The neighbors called, and while they had all kinds of excuses, there was no doubt about what it was they really wanted to see. Of course, opinions differed, and rather sharply. There were some of the older women who fearlessly denounced such conduct as unconditionally bad, but most of the women were secretly jealous and demanded that their husbands also buy a mechanical nurse-maid.

The news spread beyond the confines of the town.

Descriptions of a most interesting and erroneous nature began to appear in the newspapers. Finally, to avoid unscientific criticism, Mrs. Teeple wrote a full account of the way she was raising her child and sold it to the New York Comet, fully illustrated, for five thousand dollars. At once the Eastinghouse Electric Company was swamped with orders which they simply filed for future delivery. The entire machine was covered with patents and these were all the property of Teeple, who, for the time being, simply said that he wanted to make further studies before he would consider the sale of his rights.

For several months it seemed that the discussion would never end. College debating teams selected as their subject, Shall the Child of the Future Be Raised by the Mother or by a Psychophonic Nurse? The leaders of the industrial world spent anxious evenings wondering whether such an invention would not simplify the labor problem. Very early in the social furor that was aroused, Henry Cecil, who had taken the place of Wells as an author of scientifiction, wrote a number of brilliant articles in which he showed a world where all the work was done by similar machines. Not only the work of nurses, but of mechanics, day laborers, and farmers could be done by machinery. He told of an age when mankind, relieved of the need of labor, could enter into a golden age of ease. The working day would be one hour long.

Each mechanician would go to the factory, oil and adjust a dozen automatons, see that they had the material for twenty-four hours labor and then turn on the electric current and leave them working till the next day.

Life, Henry Cecil said, would not only become easier, but also better in every way. Society, relieved of the necessity of paying labor, would be able to supply the luxuries of life to everyone. No more would women toil in the kitchen and men on the farm. The highest civilization could be attained because mankind would now have time and leisure to play.

And in his argument he showed that, while workmen in the large assembling plants had largely become machines in their automatic activities, still they had accidents and sickness and discontent, ending in troublesome strikes. These would all be avoided by mechanical workmen; of course, for a while there would have to be human supervision, but if it were possible to make a machine that would work, why not make one that would supervise the work of other machines? If one machine could use raw material, why could not other machines be trained to distribute the supplies and carry away the finished product. Cecil foresaw the factory of the future running twenty-four hours a day and seven days a week, furnishing everything necessary for the comfort of the human race. At once the ministers of the Gospel demanded a six-day week for the machines, and a proper observance of the Sabbath.

Strange though it may seem, all this discussion seemed natural to the general public. For years they had been educated to use electrical apparatus in their homes. The scrubbing and polishing of floors, the washing of dishes, the washing and ironing of clothes, the sewing of clothes, the grass cutting, the cleaning of the furniture, had all been done by electricity for many years. In every department of the world’s activity, the white servant, electricity, was being used. In a little Western town a baby was actually being cared for by a Psychophonic Nurse. If one baby, why not all babies? If a machine could do that work, why could not machines be made to do any other kind of work?

The lighter fiction began to use the idea. A really clever article appeared in The London Spode, the magazine of society in England. It commented on the high cost of human companionship, and how much the average young woman demanded of her escort, not only in regard to the actual cash expenditure, but also of his time. When he should be resting and gaining strength for his labors in the office, she demanded long evenings at the theater or dance hall or petting parties in lonely automobiles. The idea was advanced that every man should have a psychophonic affinity. He could take her to the restaurant, but she would not eat, at the theater she could be checked with his opera cloak and top hat. If he wanted to dance, she would dance with him and she would stop just when he wanted her to and then in his apartment, he could pet her and she would pet him and there would be no scandal. He could buy her in a store, blonde or brunette and when he was tired of her, he could trade her in for the latest model, with the newest additions and latest line of phonographic chatter records. Every woman could have a mechanical lover. He could do the housework in the daytime while she was at the office, and at night he could act as escort in public or pet her in private. The phonograph would declare a million times, “I love you,” and a million times his arms would demonstrate the truth of the declaration. For some decades the two sexes had become more and more discontented with each other. Psychophonic lovers would solve all difficulties of modern social life.

Naturally, this issue of the spode was refused admission to the United States on the grounds of being immoral literature. At once it was extensively “bootlegged” and was read by millions of people, who otherwise would never have heard of it. A new phrase was added to the slang. Men who formerly were called dumb-bells, were now referred to as psychophonic affinities. If a man was duller than usual, his girl friend would say, “Get a better electric attachment. Your radio tubes are wearing out and your wires are rusting. It is about time I exchanged you for a newer model.”

In the meantime, life in the Teeple home was progressing as usual. Mrs. Teeple had all the time she could use for her literary work and was making a name for herself in the field of letters. She was showing her husband and friends just what a woman could do, if she had the leisure to do it. She felt that in no way was she neglecting her child. One hour every morning was spent in preparing the supplies and the modified milk for the following twenty-four hours. After that she felt perfectly safe in leaving the child with the mechanical nurse; in fact, she said that she felt more comfortable than if the baby were being cared for by an ignorant, uninterested girl.

The baby soon learned that the black woman was the one who did everything for her and all the love of the child was centered on her nurse. For some months it did not seem to realize much more than that it was being cared for in a very competent manner and was always very comfortable. Later on it found out that this care would not come unless it was in a very definite position on the bed. This was after it had started to roll around the bed. Dimly it must have found out that the nurse had certain limitations, for it began to learn to always return to its correct position in the middle of the crib. Naturally, difficulties arose while she was learning to do this. Once she was upside down and the nurse was absolutely unable to pin on the diaper, but the baby, frightened, started to cry and the machine picked it up and by a clever working of the mechanism put her down in the right position. By the time the baby was a year old a very good working partnership had been formed between the two and at times the nurse was even teaching the little child to eat with a spoon and drink out of a cup. Of course various adjustments had to be made from time to time, but this was not a matter of any great difficulty.

Tired with the work of the day, Mrs. Teeple always slept soundly. Her husband, on the other hand, often wandered around the house during the night, and on such occasions developed the habit of visiting the nursery. He would sit there silently for hours, watching the sleeping baby and the sleepless nurse.

This did not satisfy him, so his next step was to disconnect the electric current which enabled the nurse to move and care for the baby. Now, with the phonograph quiet and the nurse unable to respond to the stimuli from the baby and the phonograph, the Father took care of the child. Of course, there was not much to do, but it thrilled him to do even that little, and now, for nearly a half year, the three of them led a double life. The machine sat motionless all night till life was restored in the early morning, when Teeple connected her to an electric socket. The baby soon learned the difference between the living creature who so often cared for it at night and the Black Mammy, and while she loved the machine woman, still she had a different kind of affection for the great warm man who so tenderly and awkwardly did what was needful for her comfort during the dark hours of the night. She had special sounds that she made just for him and to her delight he answered her and somehow, the sounds he made pulled memories of similar sounds from the deep well of her inherited memory and by the time she was a year old she knew many words which she only used in the darkness— talking with the man — and she called him Father.

He thrilled when he held her little soft body close to his own and felt her little hand close around his thumb. He would wait till she was asleep and then would silently kiss her on the top of her head, well-covered with soft new hair, colored like the sunshine. He told her over and over, that he loved her, and gradually she learned what the words meant and “cooed” her appreciation. They developed little games to be played in the darkness, and very silently, because no matter how happy they were, they must never, never wake up Mother, for if she ever knew what was going on at night, they could never play again.

The man was happy in his new companionship with his baby.

He told himself that those hours made life worth while.

After some months of such nocturnal activity, Mrs. Teeple observed that her husband came to the breakfast table rather sleepy. As she had no actual knowledge of how he spent his nights, it was easy for her to imagine. Being an author, imagination was one of her strongest mental faculties. Being a woman, it was necessary for her to voice these suspicions.

“You seem rather sleepy in the mornings. Are you going with another woman?”

Teeple looked at her with narrowing eyelids.

“What if I am?” he demanded. “That was part of our companionate wedding contract — that we could do that sort of thing if we wanted to.”

As this was the truth, Susanna Teeple knew that she had no argument, but she was not ready to stop talking.

“I should think that the mere fact that you are the father of an innocent child should keep your morals clean. Think of her and your influence on her.”

“I do think of that. In fact, only yesterday I arranged to have some phonographic records made that, in addition to everything else, would teach the baby how to talk. I have asked an old friend of mine who teaches English at Harvard to make that part of the record, so that from the first, the baby’s pronunciation will be perfect. I am also considering having another Psychophonic Nurse made with man’s clothes. The Black Mammy needs some repairs, and it is about time that our child had the benefit of a father’s love. It needs the masculine influence. I will have it made my size and we can dress it in some of my clothes and have an artist paint a face that looks like me. In that way the child will gradually grow to know me and by the time she is three years old I will be able to play with her and she will be friendly instead of frightened. In the twilight, the neighbors will think that I am taking the child out in the baby carriage for an airing and will give me credit for being a real father.”

The wife looked at him. At times she did not understand him.

It was just a few days after this conversation that Mrs. Teeple called her husband up at the factory. “I wish you would come home as soon as you can.” “What is the matter?”

“I think the baby has nephritis.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s a disease I have just been reading about. I happened to go into the nursery and Black Mammy has had to change the baby twenty-seven times since this morning.”

Teeple assured his wife that he would be right home and that she should leave everything just as it was. He lost no time in the journey; since he had been taking care of the baby at night, it had become very precious to him

His wife met him at the door.

“How do you know Mammy had to change her so often?”

“I counted the napkins, and the awful part was that many of them were not moist, just mussed up a little.”

Teeple went to the nursery. He watched the baby for some minutes in silence. Then he took her hand, and finally he announced his decision:

“I do not think there is anything wrong with her.” “Of course you ought to know. You are such an expert on baby diseases.” His wife was quite sarcastic in her tone.

“Oh! I am not a doctor, but I have a lot of common sense. To-morrow is Sunday. Instead of golfing, I will stay at home and observe her. You leave the typewriter alone for a day and stay with me, won’t you?”

“I wish I could, but I am just finishing my book on ‘Perfect Harmony Between Parent and Child,’ and I must finish it before Monday morning, so you will have to do your observing by yourself. I think, however, that it would be best for you to send for a Doctor.”

It did not take long for Teeple to find out what was wrong. The baby was learning to talk and had developed a habit of saying, very often, sounds that were very similar to Seven. This was the sound to which the Psychophonic Nurse had been attuned to react by movements resulting in a change of napkins. The baby had learned the sound from the phonograph and was imitating it so perfectly that the machine reacted to it, being unable to tell that it was not the voice from the phonograph, or the electrical stimulus from the wet pad. When Teeple found out what was the trouble, he had to laugh in spite of his serious thoughts. A very simple, change in the mechanism blotted out the sound Seven, and cured the baby’s nephritis.

Two weeks later, the inventor introduced his wife to the new male nurse who was to be a Father substitute. The machinery had been put into a form about the size of Teeple, the face was rather like his and he wore a blue serge suit that had become second best the previous year.

“This is a very simple machine,” Teeple told his wife. “For the present it will be used only to take the baby out in our new baby-carriage. The carriage holds storage batteries and a small phonograph. We will put the baby in the carriage and attach Jim Henry to the handles, pointing him down the country lane, which fortunately is smooth, straight as an arrow and but little used. We attach the storage batteries to him and to the phonograph, which at once gives the command, “Start.” Then, after a half hour, it will give the command, “About Face— Start,” and in exactly another half hour, when it is exactly in front of the house, it will give the command “Halt.” Then you or the servant will have to come out and put everything away and place the baby back in the crib under the care of the mechanical nurse. This will give the baby an hour’s exercise and fresh air. Of course she can be given an extra hour if you think it best. If you have an early supper and start the baby and Jim Henry out just as the sun is setting, the neighbors will think that it is really a live Father who is pushing the carriage. Rather clever, don't you think?”

“I think it is a good idea for the baby to go outdoors every day. The rest of it, having it look like you, seems rather idiotic. Are you sure the road is safe?”

“Certainly. You know that it is hardly used except by pedestrians and everyone will be careful when they meet a little baby in a carriage. There are no deep gutters, the road is level, there are no houses and no dogs. Jim Henry will take it for an hour’s airing and bring it back safely. You do not suppose that I would deliberately advise anything that would harm the child, do you?”

“Oh! I suppose not, but you are so queer at times.” “I may seem queer, but I assure you that I have a good reason for everything I do.”

Anyone watching him closely that summer would have seen that this last statement was true. He insisted on an early supper, five at the latest, and then he always left the house, giving one excuse or another, usually an important engagement at the factory. He made his wife promise that at once after supper she would start Jim Henry out with the baby in the carriage. Mrs. Teeple was glad enough to do this, as it gave her an hour’s uninterrupted leisure to work in her study. The mechanical man would start briskly down the road and in a few minutes disappear into a clump of willows. Here Teeple sat waiting. He also was dressed in a blue serge suit. He would make the mechanical man lifeless by disconnecting him from the storage batteries, place him carefully amid the willows and, taking his place, would happily push the carriage down the road. He would leave the phonograph attached to the battery. When it called “About Face,” he would turn the carriage around and start for home. When he reached the willows, he would attach the mechanical nurse to the carriage and let it take the baby home. Sometimes when it was hot, the baby, the Father and Jim Henry would rest on a blanket, in the shade of the willows. Teeple would read poetry to his child and teach her new words, while Jim Henry would lie quietly near them, a look of happy innocence on his unchanging face.

The few neighbors who were in the habit of using that road after supper became accustomed to seeing the little man in the blue serge suit taking care of the baby. They complimented him in conversations with their wives and the ladies lost no time in relaying the compliment to Mrs. Teeple, who smiled in a very knowing way and said in reply :

“It certainly is wonderful to have a mechanical husband. Have you read my new book on “Happiness in the Home”? It is arousing a great deal of interest in the larger cities.”

She told her husband what they said and he also smiled. Almost all of the men he had met during the evening hour were Masons and he knew they could be trusted.

When the baby was a year old, Mrs. Teeple decided that it was time to make a serious effort to teach the child to talk. She told her husband that she wanted to do this herself and was willing to take fifteen minutes a day from her literary work for this duty. She asked her husband if he had any suggestions to make. If not, she was willing and able to assume the entire responsibility. He replied that he had been reading up on this subject and would write her out a list of twenty words which were very easy for a baby to learn. He did this, and that night she met him with a very grandiose air and stated that she had taught the baby to say all twenty of the words perfectly in one lesson. She believed that she would write an article on the subject. It was very interesting to see how eager the child was to learn. Teeple simply grinned. The list he had given her was composed of words that he and the baby had been working with for some months, not only at night, but also during the evening hour under the willows.

By that fall, Mrs. Teeple was convinced that Watson, in his book called “Psychological Care of Infant and Child,” was absolutely right when he wrote that every child would be better, if it were raised without the harmful influence of mother love. She wrote him a long personal letter about her experience with the Psychophonic Nurse. He wrote back, saying that he was delighted, and asked her to write a chapter for the second edition of his book. “I have always known,” he wrote at the end of the letter, “that a mechanical nurse was better than an untrained mother. Your experience proves this to be the truth. I wish that you could persuade your husband to put the machine on the market and make it available to millions of mothers who want to do the right thing, but have not the necessary intelligence. Every child is better without a love life. Your child will grow into an adult free from complexes.”

Mr. Teeple smiled some more when he read that letter.

It was a pleasant day in early November. If anything, the day was too warm. There was no wind and the sky over western Kansas was dull and coppery. Teeple asked for a supper earlier than usual and at once left the house, telling his wife that the Masons were having a very special meeting and that he had promised to attend. Thoroughly accustomed to having him away from home in the evening, Mrs. Teeple prepared Jim Henry and started him down the road, pushing the little carriage with the happy baby safely strapped in it. Then she went back to her work.

Jim Henry had left the house at five-fifteen. At five-forty-five he would turn around, and at six-fifteen he would be back with the baby. It was a definite programme and she had learned, by experience, that it worked safely one hundred per cent of the time. At five-thirty a cold wind began to whine around the house and she went and closed all the windows. It grew dark and then, without warning, it started to snow. By five-forty-five the house was engulfed in the blizzard that was sweeping down from Alaska. The wind tore the electric light poles down and the house was left in darkness.

And Susanna Teeple thought of her child in a baby carriage out in the storm in the care of an electrical nurse. Her first thought was to telephone to her husband at the Lodge, but she at once found out that the telephone wires had been broken at the same time that the light wires had snapped. She found the servant girl crying and frightened in the kitchen and realized that she could expect no help from her.

Wrapping a shawl around her, she opened the front door and started down the road to find her baby. Five minutes later she was back in the house, breathless and hysterical with fright. It took her another five minutes to close and fasten the door. The whole house was being swayed by the force of the wind. Outside she heard trees snapping and cracking. A crash on top of the house told of the fall of a chimney. She tried to light a lamp, but even in the house the flame could not live. Going to her bedroom, she found an electric torch and, turning it on, she put it in the window and started to pray. She had not prayed for years; since her early adolescence she had prided herself on the fact that she had learned to live without a Creator whose very existence she doubted. Now she was on her knees. Sobbing, she sank to the floor and, stuporous with grief, fell asleep.

As was his nightly custom, Teeple waited in the willows for Jim Henry and the baby carriage. He disconnected the mechanical man and put him under a blanket by the roadside; then he started down the road, singing foolish songs to the baby as they went together into the sunset. He had not gone far when the rising wind warned him of the approaching storm and he at once turned the carriage and started towards home. In five minutes he had all he could do to push the carriage in the teeth of the wind. Then came the snow, and he knew that only by the exercise of all of his adult intelligence could he save the life of his child. There was no shelter except the clump of willows. Every effort had to be made to reach those bushy trees, Jim Henry and the blanket that covered him. One thousand feet lay between the willows and the Teeple home and the man knew that if the storm continued, they could easily die, trying to cover that last thousand feet. It was growing dark so fast that it was a serious question if he could find the clump of willows. He realized that if he once left the road, they were doomed.

He stopped for a few seconds, braced himself against the wind, took off his coat and wrapped it around the crying child. Then he went on, fast as he could, breathing when he could and praying continuously. God answered him by sending occasional short lulls in the tornado. He finally reached the willows, and instinct helped him find Jim Henry, still covered by the blanket, which was now held to the ground by a foot of snow.

The man wrapped the baby up as well as he could, put the pillow down next to Jim Henry, now partly uncovered, put the baby on the pillow, crawled next to her, pulled the blanket over all three as best he could, and started to sing. The carriage, no longer held, was blown far over the prairie. In a half hour, Teeple felt the weight and the warmth of the blanket of snow. He believed that the baby was asleep. Unable to do anything more, he also fell asleep. In spite of everything, he was happy and told himself that it was a wonderful thing to be a Father.

During the night the storm passed and the morning came clear, with sunshine on the snow drifts. Mrs. Teeple awoke, built a fire, helped the servant prepare breakfast and then went for help. The walking was hard, but she finally reached the next house. The woman was alone, her husband having gone to the Masonic Lodge the night before. The two of them went on to the next house, and to the next and finally in the distance they found the entire Blue Lodge breaking their way through the snow drifts. They had been forced to spend the entire night there, but had had a pleasant time in spite of their anxiety. To Mrs. Teeple’s surprise, her husband was not with them. She told her story and appealed for help. The Master of the Lodge listened in sympathetic silence.

“Mr. Teeple was not at the Lodge last night,” he finally said. “I believe he was with your baby.”

“That is impossible,” exclaimed the hysterical woman.

“The baby was out with the new model Psychophonic Nurse. Mr. Teeple never goes out with the baby. In fact, he knows nothing about the baby. He never notices her in any way.”

The Master looked at his Senior Warden, and they exchanged “unspoken words.” Then he looked at the members of his Lodge. They were all anxious to return to their families, but there were several there who were not married. He called these by name, asked them to go to his home with him and get some coffee, and then join him in the hunt for the baby. Meantime he urged Mrs. Teeple to go home and get the house warm and the breakfast ready. She could do no good by staying out in the cold.

The Master of the Blue Lodge knew Teeple. He had often seen him under the willows talking to the baby. Instinctively he went there first, followed by the young men. Breaking their way through the drifts, they finally arrived at the clump of trees and there found what they were looking for — a peculiar hillock of snow, which, when it was broken into, revealed a blanket, and under the blanket were a crying baby, a sick man and a mechanical nurse. The baby, on the pillow, wrapped up in her Father’s coat, and protected on one side by his body and on the other side by the padded and clothed Jim Henry, had kept fairly warm. Teeple, on the outside, without a coat and barely covered by the edge of the blanket, had become thoroughly chilled.

It was days before he recovered from his pneumonia and weeks before he had much idea of what had happened or of his muttering conversations while sick. For once in his life, he thoroughly spoke of everything he had been thinking of during the past fifteen months — spoke without reservation or regard for the feelings of his wife— and above all else he told of his great love for his child and how he had cared for it during the dark hours of the night and the twilight hour after supper.

Susanna Teeple heard him. Silent by his bedside, she heard him bare his soul and she realized, even though the thought tortured her, that her ambition had been the means of estranging her husband and her child from her, and that to both of them she was practically a stranger. During the first days of her husband's illness she had placed the entire care of the child in the hands of the Black Mammy. Later it was necessary to get nurses to care for her husband, and as he grew stronger, there was less and less work for the wife. Restless, she went to the kitchen, but there a competent servant was doing the work : in the sick-room, graduate nurses cared for her husband; in the nursery, her baby was being nursed by a machine, and her little one would cry when she came near as though protesting against the presence of a stranger. The only place where she had work to do and was needed was in her study, and there the orders for magazine articles were accumulating.

She tried her soul. As judge, witness and prisoner, she tried her soul and she knew that she had failed.

Teeple finally crawled out of bed and sat in the sunshine. The house was still. One day the nurses were discharged, and his wife brought him his meals on a tray. Soon he was able to walk, and just as soon as he could do so, unobserved by his wife, he visited the nursery. Black Mammy was gone. The baby, on a blanket, was playing contentedly on the floor. Teeple did not disturb her, but went to his wife’s study. Her desk was free from papers, the typewriter was in its case and on the table was a copy of Griffith’s book on “The Care of the Baby.” He was rather puzzled, so he carried his investigations to the kitchen. His wife was there with a clean white apron on, beating eggs for a cake.

She was singing a bye-low-babykin-bye-low song, and to Teeple came a memory of how she used to sing that song before they were married. He had not heard her sing it since. Thinking quickly, he tried to reason out the absence of the nurses and the Black Mammy and the servant-girl, and the empty desk and the closed typewriter, and then it came to him — just what it all meant; so, rather shyly, he called across the kitchen:

“Hullo, Mother!”

She looked at him brightly, even though the tears did glisten in her eyes, as she replied :

“Hullo, Daddy, Dear.”

And that was the end of the Psychophonic Nurse.