The Yeast Men

by David H. Keller

The Yeast Men (1928) imagines a world where synthetic yeast-based workers replace human labor — until the artificial beings begin to develop wills of their own. "I want to see the world as it would be if the human race decided to stop work."

"And what is the matter with this aviation corps like you?" demanded Premier Plautz. "I am informed the Moronians have only a few aircraft. Of what are you afraid?"

"We fear nothing," replied Von Dort, white with suppressed anger, "but we know the truth. Since the last war, Moronia has perfected some kind of a light ray. A machine is placed every mile along their entire border. From these machines the rays go out, presumably in a fan shape. When the ray strikes an airplane, the engine not only stops but apparently explodes. No one knows how high in the air these rays go — we have never been able to rise above the range of their power. We have been experimenting and have found no way of defending the plane against the ray. So far, twenty of our planes, disguised as commercial machines, have been destroyed and our aviators killed. In every instance the bodies were brought to the frontier by the Moronians, and each time they have simply explained that something went wrong with the machinery and the plane dropped in their country. We have every reason to believe that they have perfected some power which will render impossible any attack on the enemy by air. What happened to twenty planes will happen to a thousand. That is why I said my corps was prepared for death."

The Premier started to pound the table with his fist, "Why was I not informed of this? What has been done to protect our machines? The destruction of one plane was enough to justify a new war. What have you been doing besides skulking in cowardice?"

"I made daily reports to the Chief of Staff," retorted Von Dort. "The entire matter is on record. For a month our Department of Physics and Chemistry has been working on this problem. They thought they had a satisfactory defense, and the last ten planes were supposed to have been protected, but they crumpled like the first ten."

"Colonel Von Dort is right," interrupted the Chief of Staff, General Hurlung. "All reports have been filed regularly, and a daily summary has been sent to your office. After all, it is a purely military problem. We still have the other arms of the service, the cavalry, artillery and infantry. With our cavalry alone, we could overrun Moronia. We need not worry about the air service."

"Oh! I suppose so. I suppose so!" replied the Premier, petulantly. "Still I wanted to blow them into hell with air bombs — all of them, men, women and children."

"But if you did that you would also destroy property," argued General Hurlung. "The infantry can wipe out the population just as effectively without the loss of a single structure. What worries me is this: They have a powerful ray of some kind which we know can destroy a plane at ten thousand feet. Suppose they turn these rays sidewise on our advancing army? What will happen?"

"Bah! You are growing old, General," sneered the Premier. "Have we not the artillery to blast our way through such infernal machines? Our infantry are men, not machines. They can live through any kind of hell-fire and win the victory. I am fretted at the atmosphere of doubt that covers this council of war. We will attack on the first of October, opening with artillery, following with cavalry, and mopping up with the infantry. These machines you dread so much are only machines, and all machines must be run by men. Kill the men and the machines are harmless. General Hurlung, you will prepare all branches of the army for the attack. Colonel Von Dort, you are dismissed from the service for cowardice. Go where you please, but if you are in Eupenia at the end of two days, I will have you shot."

Von Dort, drawing his dress sword, broke it over his knee and threw the pieces on the table in front of the Premier. Said Von Dort, "A country that thus rewards honesty is a land rotten to the core." The men around the table kept an awkward silence as he left the room.

Premier Plautz stood up. "You gentlemen know what to do. I will accept no excuses for incompetency. Moronia must be destroyed. We will meet again a week from today. The Secret Service had better follow Von Dort and imprison him. I do not trust him. Keep him in solitary confinement and I will deal finally with him in a few days."

Von Dort, however, was already in his automobile, leaving Eupenia as fast as he could. He paused at his home only long enough to almost throw his wife and baby and a few valuables into his car; then he started for Moronia at seventy miles an hour. Von Dort was thoroughly mad. For ten years he had served in the air service of Eupenia, advancing slowly from mechanician to Chief of the Service. During that time he had done his best. Under his leadership the corps had achieved the finest type of morale. He knew that his men were always ready to gamble on a chance in war, but he could not sit still and see his entire force sent to what he felt was certain death. During his ten years of military service he had had ample chance to study the Premier. He knew that every man who had dared to oppose Plautz had come to an unfortunate end, disgrace, exile or death. Life to Von Dort, with his wife and baby was too sweet to be sacrificed unless absolutely necessary. The former Chief of the Air Service fully realized all this. He increased the speed of his car. Moronia was his destination for other reasons than because it was the nearest border. He felt that he could trust them, as enemies, more than he could trust the other nations who were friendly to Eupenia. Also, his wife had come from that nation. She was the daughter of a former Moronian general, who died in the last war.

Von Dort had been a member of the army of occupation, and once having met this particular young lady, all his loyalty to Eupenia was insufficient to prevent him from falling in love. He felt that if he had to die, it would be better to die with his wife and baby in the mountains of Moronia, than in solitude in an Eupenian prison.

The radio message beat them to the frontier, and Von Dort saw that the barricade had been lowered. It was a sturdy wooden gate, but the automobile hit it going eighty miles an hour and reduced it to kindling. The car finally stopped, rather disheveled in looks but with the motor still running, one mile inside Moronia. There Von Dort stopped as soon as possible, having a deep respect for the vigilance and accurate shooting of the Moronia border patrol. He did not wish to arouse their suspicion in any way. The car was soon surrounded by cavalrymen, who politely but firmly asked for full details as to his identity and reason for entering the country in such a precipitous manner. Realizing that there was no reason for deceit, he gave them a brief account of his trouble and asked to be taken to the General-in-Chief of the Moronian army.

Moronia, nominally a monarchy, was in every respect democratic, except that it had a King. Every citizen felt an equal amount of reverence and fraternity for this monarch. There was rank, both in civil and military life, but promotion was by merit and without either sycophancy or tyranny. Consequently it was easier to see the Commanding General in Moronia than it was to see the Third Assistant Secretary of Agriculture in Eupenia. The Moronians lived among the mountains, and like the eagles of the crags, prized their liberty. In consequence of all this it was only a few hours before Von Dort was telling his story to General Androvitz and his staff.

They believed all that he said. Especially did they believe him after his wife talked to them in their native patois. There were some present who had known her father well. One old officer was even able to remember the celebration of her christening. The general discussion was finally ended by Von Dort.

"I fled because I knew that Premier Plautz intended to have me killed, and I came here because of my wife and because I felt keenly the injustice of another war. Moronia is to be destroyed for no other reason than selfishness and greed. The force against you is overwhelming. I see nothing save your final and complete destruction. If I have to die I want to die fighting rather than die in a prison, or shot, or hanged like a criminal. I offer you my services, General Androvitz, and am willing to serve your country in any capacity."

The General at once sent for the King to join their deliberations. Rudolph Hubelaire came, a little, withered, one-armed man with the fire of a lion in his eye. He heard the news without changing expression. The other men watched him anxiously. Finally he spoke.

"We can die but once. Resistance, in our weakened state, will be but a grand gesture. Eupenia may conquer the country but she will never enslave our patriots. They and their families may die, but they will never surrender. When the time comes, we will fight. When that is over, the survivors will retire to our mountain forts. There we will live with the goats and chamois. I am sorry that it all has to end thus, but we have done our best. One more invention like our ultra-light rays would have saved us — but our scientists have done their best, and as we have failed, so have they. Colonel Von Dort, we trust your honesty and welcome you to our ranks. Your desire to die on the field of battle will probably be realized."

The meeting was just breaking up, each participant ready to carry the sad news to his friends, when the guard at the door announced the presence of Mr. Billings, one of Moronia's staff of scientific investigators.

"Poor Billings," said the King, "a harmless fellow from America. He has worked in our laboratory for years without pay except for his bare expenses, and he is about broken-hearted because so far he has failed to make any discovery of importance. I wish we could get him back to America before war begins. Let us humor the old gentleman and listen to his story. I want you to show his age the proper respect. Let there be no levity. His loyalty and faithful endeavor demand our greatest courtesy."

Billings came in and was seated by the King. He was stooped-shouldered, bald and trembling. His high-pitched voice cracked like static under his excitement.

"Your Majesty and Gentlemen," he said. "After years of the most tedious experimentation, I have finally discovered a method of defending ourselves against the Eupenians."

"Fine!" said the King. "Now tell us all about it."

"I propose that we make an army of Yeast Men."

"That is a fine idea, Mr. Billings," said the King soothingly. "I am sure that your discovery has merit. Now I want you to go over to America and take a long vacation, and after you are thoroughly rested you can come back and visit us again."

"But you do not understand," pleaded the old man. "I suppose you think that I am senile. The invention is complete and I am sure it will work. It is practical and simple. The one machine I have made functions perfectly. It can easily be duplicated, and anyone can run it. All we need is an abundance of yeast and hundreds of machines. You shoot the little fellows out like bullets from a machine gun."

"Well, what happens then?" asked General Androvitz.

"They just grow and walk around a little and then they die."

"If they do that they will be typical soldiers," interrupted the Chief of the Artillery Service. "That is about all we will do between now and Christmas."

"But in dying they will win the victory!" eagerly chirped the inventor in his high-pitched cricket voice. "Cannot you understand that they will die and rot in Eupenia?"

The King gently took the old man by the shoulder and as he talked the tears came to his eyes.

"My dear Billings. The thing you describe is just a soldier. For hundreds of years the Moronians have died in defense of their country. They had died and rotted, and yet we, as a nation, have slowly withered away. Brave men by the thousand have done just that, and to what avail? Your eagerness to help has worried you sick. Go and take a long rest. Yeast Men and real men may die and rot but our dear Moronia is doomed."

"But cannot you see it?" pleaded the inventor. "Oh! Please try to see it. Yeast Men by the millions and billions walking into Eupenia and rotting there. Cannot you see how it is going to work?"

"I beg your pardon," asked General Androvitz, "but did you say billions?"

"I did. A few drops of yeast grows to be a soldier six feet tall. Give me as many machines as those you made to generate the anti-aircraft rays and I will produce Yeast Men by the million. I will make a million every day as long as it is necessary."

"And they live just so long and then die?" asked the King.

"Yes, they live about three days. During that time they are able to move about twenty-five miles. Then they die and rot."

"A fairy tale," said the Premier, who, up to this time, had kept silent.

"But I can prove it. I have made one. If you see just one of them, will you believe it? Let me show you just one!"

The King held up his hand for silence.

"Gentlemen, let me talk to Billings. Please do not interrupt. He is nervous — and so am I. We must get to the real truth in this matter. I would never forgive myself if he really found something of value and lost it because of our incredulity. Now, Friend Billings, let us pretend that we are alone. Pay no attention to these other men. Listen to my questions, and answer them as simply as you can. Remember that I am not a scientist and do not understand big words. Now, how much yeast does it take to make a soldier?"

"About two drops."

"How big does he grow?"

"About six feet tall."

"Do they look like real men?"

"Just a little. You see they are made of dough."

"Do they walk as we do?"

"No. It is sort of a creeping shuffle — amoeba movement."

"If they are not destroyed, how long will they live?"

"About three days."

"What happens then?"

"They cease to grow or move. They die and decay — rot."

"Suppose one of them is shot or has his head cut off with a saber, or is torn into pieces by a cannon ball, what then?"

"Each piece would keep on living and growing and moving till the end of the third day."

"You said they would move at eight miles an hour?"

"Yes, if nothing stopped them. They would be in Eupenia at the end of forty-eight hours, and by the end of the third day they would rot there."

"Are you sure of all this?"

"It worked out in the laboratory."

"What makes them grow?"

"It is a peculiar form of yeast. In the machine we compress it. Just as soon as it is liberated, it begins to extract nitrogen from the air, and expands. It not only expands, but it actually grows by the rapid division of the yeast cells."

"I do not understand it," said the King, "but I am willing to take your word for it. What makes them move?"

"Radiant energy. Before the yeast is put into the guns, it is thoroughly energized with a form of radium."

"But these peculiar creatures cannot fight: they have no weapons: how can they win a war?"

"By their rotting, Your Majesty. I have tried to make that plain to you. They die and rot."

"You mean they decay?"

"Exactly. They dissolve into pools of slime. They form a puddle about three feet in diameter and weighing about thirty pounds."

"How would such decaying masses stop an invading army?"

"It is their stench that will stop them. The yeast is mixed with culture of Bacillus Butericus and other foetid germs. These grow in the dying and dead yeast, and produce the smell."

"That may be true, but your idea that it will stop an army is all nonsense. No soldier was checked just by a smell."

"But this will stop them. I have a little bottle here. It has one drop of the end slime diluted a thousand times. Have one of your officers smell it."

"Any volunteers?" asked the King.

"Certainly," answered the Chief of Artillery. "I have been in three wars and have smelled everything horrible known to any form of campaign. It will never hurt me."

The inventor held the opened bottle under the military man's nose. Roughly, the soldier took two deep smells. Then Billings corked the bottle, while the volunteer slumped from the chair down to the floor and lay there, white, sweating and vomiting. The others hastened to help him loosen his collar.

"My God!" exclaimed the King. "Just two whiffs from a bottle containing a thousandth of a drop, and each dead Yeast Man produces thirty pounds of the stuff. Will it kill?"

"Not men, but plants," was Billings' reply. "Look at this." He emptied the bottle on a large clay jar holding a blooming cyclamen. At once the plant withered and died. A curious foetid smell filled the room. The King rose hastily and sought an opened window. So did the rest seek doors and open windows, while carrying the fainting Chief of the Artillery Service with them.

As soon as they got outside the room, in the pure air, the King turned to the inventor:

"Show me just one man like those you describe, Mr. Billings — just one man, and the resources of the kingdom are at your command."

"I have made them. I have one now that is nearly three days old. My assistants have been leading him around an old deserted race track. You see, they go in a straight line unless they are led, and the only way we could keep him under observation was to lead him around in a track."

"We will go and see him," said the King, "and we will take with us the Professor of Mathematics from the University. Gentlemen, follow us in your cars."

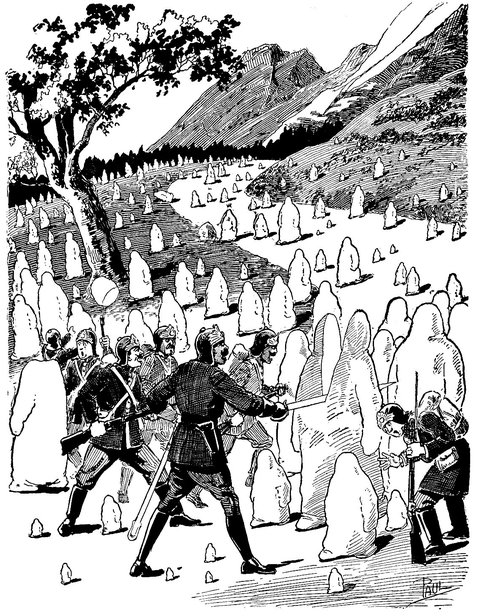

The party reassembled at an old race track, overgrown with grass and a quarter mile in circumference. Slowly walking around this track was an assistant from the Moronian laboratories. Other men were resting on a bench. The walking man held a rope and was leading by it a peculiar creature. It was a Yeast Man.

Imagine a six-foot man of dough, with a crust hard enough to hold it erect, yet viscid enough to allow it to move forward. A creature with a head but no face, with spade-like hands without fingers, and instead of two legs and feet, simply a body like a skirt, which rested firmly on the ground on a two-foot base. It was the convulsive movement of this base and the mass of fermenting yeast above it that in some way enabled it to move slowly over the ground. It was such a creature, with a broad canvas band around its waist, that the Moronians saw being led around the track. Mr. Billings ran forward eagerly and conferred with his men. Then he returned to the group of officers surrounding the King.

"They report that it had gone around the track ninety-nine times. That is twenty-three miles and nearly twenty-four. It was four feet tall at the end of the first day and at the end of the second day it was full grown. It is now nearly three days old, and if our calculations are correct, it will soon die."

The Yeast Man slowly moved around the track. Just in front of the tumbled-down grandstand it stopped. Billings instructed his men to take off the canvas belt. The party gathered around the motionless figure. Suddenly it began to grow shorter and stouter. It swayed, and finally out of balance, started to fall forward, bending at the waist. An unpleasant odor filled the air. Suddenly it bent double, and literally melted into a pool of greenish yellow slime. The odor grew increasingly frightful, so that it drove the observers further and yet further away. The grass touched by the slime withered and died.

The King turned to the professor of mathematics. "Professor," he said, "estimate the size of that puddle. Multiply it by five billion. Estimate the territory filled with that odor. Suppose such masses, five billion such masses, were scattered equally over Eupenia. What would be the result?"

The professor figured on the back of an old envelope. He used the stub of a short pencil which he nervously stuck in his mouth after every fifth figure. Finally he said, "If you could arrange to have them die at different places, the whole of Eupenia would be covered about six inches deep."

The King turned to his staff:

"I am satisfied, gentlemen. We will have hundreds of these machines made, and when we are ready to begin operations, Mr. Billings can make five thousand Yeast Men to start with. Our citizens can lead them for three days, and just as they are about to die, we will turn them loose on all the highways and open spaces leading to Eupenia. At the same time, we will start making them by the million. Our attack will come before the enemy's ready. If it works, we will obtain a bloodless victory. The only way we can make a success of it is to spring it on them as a total surprise. Cut all the wires leading to Eupenia. Confiscate at once all the radio sets. Be more careful than ever in watching the suspected spies. It would not be a bad idea to imprison them till this is over. Put a triple guard on the border. Permit no intercommunication. Turn over the entire resources of the kingdom to Mr. Billings and his associates. At the same time do not omit a single item leading to the preparedness of our little army. I understood Von Dort to say that we would be attacked on the first of October. We will attack before then — just as soon as Billings is ready. Have any of you a suggestion?"

"Yes," said the Chief of Artillery, still pale and sweating from his recent nausea. "Why not let me follow the Yeast Men up and blow them to pieces with shrapnel? Make five yeast pieces and five stench pots out of each Yeast Man?"

"I think," replied the King, "that the Eupenians will be only too anxious to do that work for us. Again I repeat, gentlemen, that we must observe the greatest secrecy. Keep the anti-aircraft machines in constant operation, especially on cloudy days. May God save our Country and bless our good friend, Mr. Billings. Now, Gentlemen, to work, day and night, without rest, to make this machinery, gather an abundance of material and train men to use the machines."

Near every road connecting the two countries, large canvas camouflage screens were erected. Captive observation balloons sent up by the Eupenian air service reported no massing of Moronian troops. Behind these canvas screens, however, thousands of the men and women of the little mountain kingdom took turns leading five thousand Yeast Men in their monotonous journey toward death. All day and all night on the 17th, 18th and 19th of September, these five thousand Yeast Men moved and grew behind the protecting curtains. Their genesis had been so timed that at dusk on the third day they were two days, twenty-three hours and thirty minutes old. Then they were turned loose on the main highways and were started on their slow shuffle toward Eupenia. Some, of course, were checked at the border barricades. Others crawled around or over and had advanced several hundred yards into the enemy's country before dissolution occurred.

In the meantime peculiar-looking machine guns were being placed at intervals of one mile, each manned by a group of trained Moronian soldiers. These guns were simple in construction, and mounted on sturdy tripods. Above each was a small hopper, from which yeast was fed to a small but powerful press operated by condensed air. Each blow of the ram produced a Yeast Man one-eighth of an inch high. These were dropped into the barrel of the gun and were blown out into the air several hundred feet away from the gun. Like thistle down they floated, gradually dropping to the ground, base downward and head erect. Immediately on touching the earth, they began their peculiar shuffling movement, which was to continue in the exact direction in which they had started. As the guns worked, they revolved slowly through a forty-five degree horizontal arc.

Each gun fired two Yeast Men a second. That meant one hundred and twenty a minute; seven thousand, two hundred an hour, or 172,800 in the course of twenty-four hours. There were seven hundred guns made, but only about five hundred were in actual use at any one time; the others acting as replacements. Counting the total time these five hundred guns were in use, it was later estimated that they were fired about ten days. This made a total of 1,728,000 for each gun, or a grand total of eight hundred and sixty-four million Yeast Men manufactured during the campaign. Each Yeast Man, dead, produced thirty pounds of end-slime, a total of 12,960,000 tons. It will be remembered that this slime, in a one-to-a-thousand dilution, was sufficiently strong to produce disabling vomiting.

These guns began operations twenty-four hours before the five thousand fully-grown Yeast Men were liberated. They then moved slowly forward, and behind them came successive waves of smaller and yet smaller men of dough. At the end of the first twenty-four hours, the oldest of the Yeast Men who had been shot from the five hundred guns, were nearly four feet high. The woods and fields of Eupenia bordering on Moronia were dotted with the peculiar creatures.

The statement made by Mr. Billings that he would be able to manufacture them by the billions never materialized. The machines worked more slowly than he had anticipated. It was also seen that a large number were caught in trees and ravines and were unable to continue their march. Yet a sufficient number reached the smooth highways and level pastures to do everything that was required of them. Also the work was facilitated later in the campaign by mounting the guns in airplanes and literally showering the towns and cities with the little fellows. This, however, was not attempted till it was seen that the morale of the Eupenians was completely destroyed.

During the entire campaign not a single Moronian died of injuries incident to warfare, though time and again many of them fell exhausted from lack of sleep. The radium workers not only received painful burns but were affected for several years as the result of the prolonged exposure to the mysterious emanations from the weird element. These, however, were but slight horrors of war compared with what might have happened had the Eupenian attack found the Moronians in their previous defenseless condition.

During September, 1930, all had been active in the kingdom dominated by Premier Plautz, who was the real ruler of Eupenia, in place of the feeble-minded King. All branches of the army, including the aviation section, had been mobilized. Fifty thousand trained and well-armed men were in camp ready to begin the destruction of the little mountainous kingdom of Moronia. The attack was timed to begin on the first of October. Premier Plautz no longer was content with his usual statement that Moronia must be destroyed. He was now saying that the time had come for the actual work of destruction to begin. An interesting fact was that the escape of Col. Von Dort and his admission into Moronia as a place of refuge was to be made the actual causa belli. On the thirtieth of September his surrender was to be demanded within twenty-four hours. If it were not conceded, the Eupenian army would at once advance. If the demand were complied with, the army would advance anyway. Moronia, as far as Premier Plautz was concerned, had to be destroyed.

A broad highway connected the capital cities of the two kingdoms. This was the road used by Von Dort in his dramatic flight for safety. It was here at the border that he had crashed through the barricade. At this point, the Eupenian border guard was commanded by Lieutenant Kraut, and under him was a company of ninety privates and noncommissioned officers. On the evening of the nineteenth of September, the Lieutenant was writing his daily report and wishing for something to happen to relieve the deadly monotony of daily routine. Just as he had finished this report and was signing it, a sentry rushed in and stated that a number of peculiar looking naked men were at the boundary gate trying to enter the country. Suspecting a trap, the Lieutenant at once called his entire force to arms and personally investigated the matter. When he approached the barricade, he was astonished to see a number of grayish white creatures, six feet high, moving aimlessly on the other side of the gate. They had heads without features, bodies without legs, arms without fingers. Cautiously, he touched one and shivered at the peculiar soft sensation that was imparted by the animal's skin. Realizing that his men were watching him closely and that any sign of nervousness on his part would be communicated to them, and feeling certain, too, that each of the peculiar shapes was but a mask and cloak for a Moronian soldier, he drew his revolver and shot one of the odd things several times through the heart section. The bullet holes closed and there was no blood. The thing kept on with its curious shuffling movement.

"Attention, men," he commanded. "Open the gates and we will take them all prisoners. God knows what they are, but they cannot hurt us anyway, and we will hold them till to-morrow and then send them in trucks to the General-in-Chief."

His men obeyed the command but there were many more of the new creatures than there were soldiers and thus while over seventy were captured, several hundred passed the barricade and started moving down the road.

In the guard-house the telephone was ringing violently. Headquarters wanted to know if anything new had developed and whether Lieut. Kraut and his command were safe. Disquieting messages were being received from the other outposts and they wanted an immediate report. Lieut. Kraut started to tell about the peculiar things he had captured, and the Major at the other end of the line reprimanded him for being drunk again. The Lieutenant protested that he was perfectly sober. The Major demanded an exact description of the new animal. The Lieutenant had one brought into his office and held near his desk while he gave a verbal description over the telephone. Even while he was talking, the animal softened and started to melt. The Lieutenant described the process as long as he could talk. Even while writhing on the floor in deadly nausea and vomiting, he tried to tell what had happened, but his retching only convinced the Major at Headquarters that the Lieutenant was beastly drunk. Finally the Lieutenant was dragged out of the office by two of his men, who waded through pools of indescribable filth to rescue him. He was too sick to realize that his entire command had fled from the Post, though here and there one of the soldiers lay on the road too sick to move. Outside, the road was impassable on account of the puddles of slime which dotted it. Cursing and vomiting, the Lieutenant staggered through the dark woods, seeking pure air and freedom from the stench, which even in memory produced a recurrence of the prostrating nausea.

Meantime those of the novel creatures who still lived were shuffling slowly down the broad highway, every few minutes losing one of their number by death and decay. In the dark hours of the night they died unseen and unmourned, but each of them left behind a horrible evidence that they had once lived. Over the pools of slime others of their kind walked, some three feet high, others a foot high and here and there could be seen midgets only a few inches high but resembling their larger brothers in every detail. When the sun rose, there also arose from every road between the two kingdoms, the smell of death a million times magnified. It was as though Moronia were surrounded by a circle of decay three miles deep. Meantime the smaller, younger Yeast Men were advancing into Eupenia, through the woods and meadows, tumbling into ravines, catching fast in trees and bushes, falling into streams and being swept away in the current, and yet ever with a sound like soft snow falling, the little ones, new born, were floating down through the air like goose down, and on and on the machines along the border of Moronia kept up their gentle thump-thump-thump and with each thump was created one more new life, one more soldier, brainless, fearless, bloodless, filled with the urge to keep on moving till dissolution came. And they all moved downhill, from the mountainous Moronia, into the enemies' more level country. They were perfect soldiers.

All the Eupenian outposts had experienced the same novel sensations and made the same report that was made by Lieutenant Kraut as soon as he was able to talk. None of the officers who came to headquarters to report could produce any proof that they really had seen such massive monstrosities. Every officer had to periodically stop his verbal report till another period of vomiting had passed. The Commander-in-Chief thoroughly believed that they had gone drunk and insane through the effects of cheap whiskey and put them all under arrest. At the same time he sent several spies on motorcycles to make a thorough investigation. These returned babbling hysterically of an army of creatures of all sizes, and every spy was vomiting with the same enthusiastic persistency that the officers had shown. The Commander-in-Chief began to curse the morals of his army and went and started to get "drunk" himself.

Even then Eupenia might have saved herself, though it is a question as to just how efficacious any campaign of shrapnel, or any building of fences or digging of ditches, would have proved. What really happened was no doubt inevitable, yet the fact remains, and it is of historical importance, that twenty-four hours passed before any offensive was started. Data was gathered and observations and lengthy reports were made. Otherwise nothing was done. These reports, especially from the border regions, were of such a varied and fantastic nature that little value could be placed on them.

Finally Premier Plautz decided to personally investigate the situation. He took with him the Chief-of-Staff and a group of scientists from the University. They found the new creatures by the hundreds of thousands and of all sizes. They also came as near as they could to several of the puddles of end-slime. An effort to observe these carefully with the aid of gas masks was useless. Even when some of the foetid material was gathered at the end of a long pole, it could not be brought close enough to make any observations of value. Several of the things were carefully studied, both chemically and anatomically, but not a single observer connected the moving oddities with the pools of decay. It must be remembered that after the first hour of the offensive no more Yeast Men had died, and the reports of the rapid dissolution of the first wave were entirely discredited.

For the first time in his life, Premier Plautz was at a loss to know what to do. To him the entire situation was incomprehensible. At one side of his automobile a five foot abortion was slowly moving, its featureless face asking only one question. "Why was I made?" In the Premier's hand was a watch crystal and on the glass was a new creation, barely a quarter of an inch high, in every respect the exact duplicate of its brother standing by the side of the car.

"What does this mean, Professor Owens?" the puzzled Premier asked the Chemistry teacher. "What kind of things are these? They cannot fight. They have no weapons, no brains, no blood. All they know is how to grow and move forward. Evidently they come from Moronia, but for what reason. Is it a declaration of war?"

The old Professor answered to the best of his ability and what he said was surprisingly near the truth.

"They are just Yeast Men, Your Excellency. I have examined them in every way, chemically and microscopically and they are just peculiarly shaped masses of dough animated by some very active yeast. Their movements resemble dough overflowing a pan. I do not know what they mean but I do know what they are. I have had one cut up and baked in loaves and it tastes like a fairly good kind of whole wheat bread."

Here the Chief-of-Staff interrupted.

"Of course we could consider it as a declaration of war and attack, but what would be the influence on the world's opinion of us? Reporters would rush in from the Paris and London papers. They would make us a laughing stock of the universe. What could we say? That we were afraid of lumps of yeast? That we were using our artillery on potential loaves of bread? So far, these creatures have not committed a single depredation. No lives have been lost, not a house burned, not a single pig or chicken killed. Think what a reporter from an American paper would do to us if he had a chance to write it up? How he would describe our infantry pouring bullets into dough, our brave cavalrymen cutting the heads off of bread men? Far better would it be to take them as fast as we can and distribute them among all of our people and let them make bread with them. That would be a joke. The Eupenian nation being fed at the expense of the very enemy who hates them so."

"I believe you are right!" answered the Premier. "There is certainly nothing in such creatures to be afraid of, though their number seems to be increasing hourly. It was all well enough for the ignorant peasants to run in terror from their farms, but the city folk will look on it as a great joke — especially if we use the proper kind of propaganda. Suppose we go back at once to the capitol and prepare a statement for the press."

The next edition of The Staatsbote, the leading afternoon paper in Eupenia, ran the following news item on the front page:

HAVE YOU A LITTLE YEAST MAN IN YOUR HOME? IF NOT, WHY NOT?

All citizens are urged to at once provide their homes with one or more Yeast Men. These peculiar creatures are very harmless and the Department of Chemical Research assures us that they make a very fair quality of bread. They come in all sizes. When little, your children can play with them as dolls; when full sized, they can reduce the High Cost of Living.

All citizens having automobiles are commanded to go into the country regions and bring to their homes as many of these Yeast Men as they can accommodate. Bring extra ones for your poorer neighbor.

Army trucks will make regular trips to bring these Yeast Men to the Capitol. After they are paraded through the streets they will be distributed to all families not yet provided.

This item was published on the afternoon of the second day. All that afternoon and evening thousands of Yeast Men were brought into the towns and cities of Eupenia in private automobiles and army trucks. The Premier, quick to act for his personal advantage issued an order canceling all contracts for flour and directing that the army be supplied with bread baked from the dough creatures. Each company in the army was directed to forage for its own supply and to keep them in their tents till they were needed for baking bread.

The next morning, which was the beginning of the third day of the Moronian offensive, thousands of the Yeast Men were exhibited in parade through the streets of the Eupenian capital, each one in charge of a soldier. The citizens laughed till they cried at the comical spectacle, and slapped each other on the back as they pointed out "the only kind of soldiers Moronia could attack with." Within a few hours it became quite the fashion to have your own personal Yeast Man. Children walked around leading their little dough pets. High School pupils painted theirs with the class colors and numerals. These things could be led and guided. Herr Schmidt, Honorable President of the Ancient Order of Eupenian Cab Drivers, made a harness for a pair and had them draw a light buggy through the streets, with his grandson for driver.

That third day was a fete day for all Eupenia. The Premier, however, had gone to unnecessary labor to bring the Yeast Men into the city. By noon they were beginning to arrive of their own accord, by the hundreds of thousands: by afternoon the streets were crowded with them. Instead of being a joke, this thing was becoming a problem. They were gathered into the parks, thrown into the cellars, herded out into the country, but still they came in increasing numbers. Every house had one or more: not a basement but was filled with a reserve supply; the barracks and tents of the army were overrun. The morning paper estimated that there was enough dough to provide bread for half a year. The problem now was not how to get them into the city but how to get them out and keep them out. In spite of Premier Plautz' reassurance in the afternoon paper and definite orders for the army to advance on the next day, the entire populace was beginning to be worried.

Their chief anxiety arose because of the fact that they could not understand or comprehend the situation.

Then, just towards evening, the Yeast Men began to die. Not all at once, but in increasing numbers. And twilight advanced to add darkness to the horror. Then they died by thousands and hundreds of thousands all over Eupenia. It was bad enough in the country districts where here and there the pools of end-slime dotted the woods and the meadows; but in the cities, especially in the Capital, the immediate result was a panic. In hut and palace, home and barracks, life was no longer possible on account of these thousands of puddles of nausea-producing slime. The houses were filled with it. The streets were filled with it. The only living things that were unaffected were the Yeast Men waiting for their turn to die. With sightless faces they shuffled along the streets passing unconcerned through the decayed bodies of their brothers with apparently only one idea — to keep moving till death came to enable them to add their bit to the defence of their country.

The people fled. Sick and sweating, pale-faced and gasping, incapacitated and vomiting, they ran from the terror. The army fled, cursing the Premier for thinking to feed them on such putrid offal. Nothing could hold them, or restore discipline. And around Moronia was a widening, desolate, deserted ring in which there was no living thing.

The people fled to the border. The neighboring Kingdoms, however, friendly as they were to Eupenia, thought of their own safety. In this strange vomiting, in the tales of delirium told by the first refugees, they thought they saw symptoms of a new and deadly contagious disease and at once threw a line of bayonets along their borders and forbade emigration from the stricken land.

Eupenia deserted her Capital without shedding a drop of blood.

Premier Plautz, as soon as he had sufficiently recovered from his own personal vomiting, to consider the matter, called a meeting of his Staff and ordered the advance to begin against the enemy. This, he said, was only a new method of conducting war. Were they to be conquered by smells or inert lumps of yeast? Let the artillery blow them to pieces. Let the cavalry cut them to pieces. The infantry could build fires and burn them. A faithful remnant of the once proud army attempted to follow out his orders but no soldier, however brave, can continually fight on an empty stomach, and no officer, however capable, can give orders while constantly vomiting. The army, from the General-in-Chief down to the privates, were continually sick with the sickness of Jonah's Whale.

The whole resistance was hopeless. The Yeast Men arrived day after day in increasing numbers and they could not be killed. They could be mutilated, dissevered, decapitated, but each piece lived and moved onwards.

Efforts at their destruction only added to the horror, and put the finishing touch to the destruction of morale.

What use cutting a thing to pieces when each piece kept on living and advancing? How could an enemy be killed when it could not bleed?

Eupenia was hysterical.

On the sixth day, the army revolted, killed Premier Plautz and declared the Kingdom a Republic.

Immediately they sued for peace by radio. Moronia suspected a trap and refused to grant an armistice. Her guns continued the deadly shower. Finally, on the tenth day of the unequal struggle, peace was declared.

Afterwards, the world blamed Moronia for not granting an immediate armistice, but it is only fair to her to say that she did not know the full horror of the war at the time and never did realize it as the Eupenians did. She was anxious enough for peace, but she wanted a peace that would be permanent.

But Eupenia not only wanted peace, she wanted help to rid her of the millions of tons of terrible end-slime. Mr. Billings was called in for advice. He laughed at the question.

"The smell only lasts for ten days," he said, "and then dies out and the slime simply becomes a highly concentrated manure, more rich than any commercial fertilizer that we have yet discovered. The fields of Eupenia will be the more fertile because of this manure. Tell the farmers to be patient and hopeful. They will have fine crops next year. The city people can shovel it up for their window boxes: it will grow wonderful violets."

Later on, at the close of the Peace Festival, Mr. Billings was decorated. The little old King, Rudolph Hubelaire, put his one arm around the inventor and kissed him on both cheeks. Then he pinned the decoration of the Golden Moronian Eagle on him, while the people cheered.

"I want to raise your salary," said the King.

"The only rays I am interested in," replied the inventor, who had not been paying much attention to what the King was saying, "are the light-and energy-rays. I have another idea about them which I think I can work out if you will let me have some money for my experimentation."

"You can have all the money you want!" was the King's eager answer. "But tell me one thing. What made those Yeast Men grow and move the way they did?"

"It was like this, Your Majesty. They were just yeast cells but they were filled with a special dynamic energy, a very special form of energy. I could tell you all about it, but I am afraid that it would be hard for you to follow my technical explanation."

"I know I couldn't," laughed the King. "I wish you could put that kind of energy into my people. We could win the commerce of the world. But I suppose you can do things with yeast that you cannot do with human beings. Now let us go to the banquet. The people are anxious to hear you."

And Mr. Billings of the United States of America said to Rudolph Hubelaire, King of Moronia,

"I am not very good at speechifying."

Want to save this story?

Create a free account to build your personal library of favorite stories

Sign Up - It's Free!Already have an account? Log in