What Happened to Alanna

by Kathleen Norris

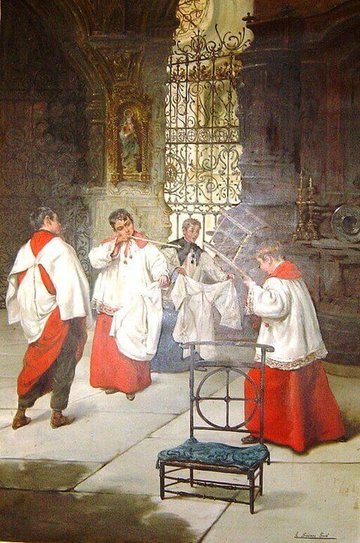

"A surplice is a thing you make in the house like any other dress, and you know how girls feel about the things their brothers wear, especially if they love them! There never were sisters more devoted than Marg'ret and my Alanna!"

A capped and aproned maid, with a martyred expression, had twice sounded the dinner-bell in the stately halls of Costello, before any member of the family saw fit to respond to it.

Then they all came at once, with a sudden pounding of young feet on the stairs, an uproar of young voices, and much banging of doors. Jim and Danny, twins of fourteen, to whom their mother was wont proudly to allude as "the top o' the line," violently left their own sanctum on the fourth floor, and coasted down such banisters as lay between that and the dining-room. Teresa, an angel-faced twelve- year-old in a blue frock, shut 'The Wide, Wide World' with a sigh, and climbed down from the window-seat in the hall.

Teresa's pious mother, in moments of exultation, loved to compare and commend her offspring to such of the saints and martyrs as their youthful virtues suggested. And Teresa at twelve had, as it were, graduated from the little saints, Agnes and Rose and Cecilia, and was now compared, in her mother's secret heart, to the gracious Queen of all the Saints. "As she was when a little girl," Mrs. Costello would add, to herself, to excuse any undue boldness in the thought.

And indeed, Teresa, as she was to-night, her blue eyes still clouded with Ellen Montgomery's sorrows, her curls tumbled about her hot cheeks, would have made a pretty foil in a picture of old Saint Anne.

But this story is about Alanna of the black eyes, the eight years, the large irregular mouth, the large irregular freckles.

Alanna was outrunning lazy little Leo--her senior, but not her match at anything--on their way to the dining-room. She was rendering desperate the two smaller boys, Frank X., Jr., and John Henry Newman Costello, who staggered hopelessly in her wake. They were all hungry, clean, and good-natured, and Alanna's voice led the other voices, even as her feet, in twinkling patent leather, led their feet.

Following the children came their mother, fastening the rich silk and lace at her wrists as she came. Her handsome kindly face and her big shapely hands were still moist and glowing from soap and warm water, and the shining rings of black hair at her temples were moist, too.

"This is all my doin', Dad," said she, comfortably, as she and her flock entered the dining-room. "Put the soup on, Alma. I'm the one that was goin' to be prompt at dinner, too!" she added, with a superintending glance for all the children, as she tied on little John's napkin.

F.X. Costello, Senior, undertaker by profession, and mayor by an immense majority, was already at the head of the table.

"Late, eh, Mommie?" said he, good-naturedly. He threw his newspaper on the floor, cast a householder's critical glance at the lights and the fire, and pushed his neatly placed knives and forks to right and left carelessly with both his fat hands.

The room was brilliantly lighted and warm. A great fire roared in the old-fashioned black marble grate, and electric lights blazed everywhere. Everything in the room, and in the house, was costly, comfortable, incongruous, and hideous. The Costellos were very rich, and had been very poor; and certain people were fond of telling of the queer, ridiculous things they did, in trying to spend their money. But they were very happy, and thought their immense, ugly house was the finest in the city, or in the world.

"Well, an' what's the news on the Rialter?" said the head of the house now, busy with his soup.

"You'll have the laugh on me, Dad," his wife assured him, placidly. "After all my sayin' that nothing'd take me to Father Crowley's meetin'!"

"Oh, that was it?" said the mayor. "What's he goin' to have,--a concert?"

"--and a fair too!" supplemented Mrs. Costello. There was an interval devoted on her part to various bibs and trays, and a low aside to the waitress. Then she went on: "As you know, I went, meanin' to beg off. On account of baby bein' so little, and Leo's cough, and the paperers bein' upstairs,--and all! I thought I'd just make a donation, and let it go at that. But the ladies all kind of hung back--there was very few there--and I got talkin'--"

"Well,'tis but our dooty, after all," said the mayor, nodding approval.

"That's all, Frank. Well! So finally Mrs. Kiljohn took the coffee, and the Lemmon girls took the grab-bag. The Guild will look out for the concert, and I took one fancy-work booth, and of course the Children of Mary'll have the other, just like they always do."

"Oh, was Grace there?" Teresa was eager to know.

"Grace was, darlin'."

"And we're to have the fancy-work! You'll help us, won't you, mother? Goody--I'm in that!" exulted Teresa.

"I'm in that, too!" echoed Alanna, quickly.

"A lot you are, you baby!" said Leo, unkindly.

"You're not a Child of Mary, Alanna," Teresa said promptly and uneasily.

"Well--well--I can help!" protested Alanna, putting up her lip. Can't I, mother? "Can't Is, mother?"

"You can help me, dovey," said her mother, absently. "I'm not goin' to work as I did for Saint Patrick's Bazaar, Dad, and I said so! Mrs. O'Connell and Mrs. King said they'd do all the work, if I'd just be the nominal head. Mary Murray will do us some pillers-- leather--with Gibsons and Indians on them. And I'll have Lizzie Bayne up here for a month, makin' me aprons and little Jappy wrappers, and so on."

She paused over the cutlets and the chicken pie, which she had been helping with an amazing attention to personal preference. The young Costellos chafed at the delay, but their mother's fine eyes saw them not.

"Kelley & Moffat ought to let me have materials at half price," she reflected aloud. "My bill's two or three hundred a month!"

"You always say that you're not going to do a thing, and then get in and make more than any other booth!" said Dan, proudly.

"Oh, not this year, I won't," his mother assured him. But in her heart she knew she would.

"Aren't you glad it's fancy-work?" said Teresa. "It doesn't get all sloppy and mussy like ice-cream, does it, mother?"

"Gee, don't you love fairs!" burst out Leo, rapturously.

"Sliding up and down the floor before the dance begins, Dan, to work in the wax?" suggested Jimmy, in pleasant anticipation. "We go every day and every night, don't we, mother?"

"Ask your father," said Mrs. Costello, discreetly.

But the Mayor's attention just then was taken by Alanna, who had left her chair to go and whisper in his ear.

"Why, here's Alanna's heart broken!" said he, cheerfully, encircling her little figure with a big arm.

Alanna shrank back suddenly against him, and put her wet cheek on his shoulder.

"Now, whatever is it, darlin'?" wondered her mother, sympathetically, but without concern. "You've not got a pain, have you, dear?"

"She wants to help the Children of Mary!" said her father, tenderly. "She wants to do as much as Tessie does!"

"Oh, but, Dad, she can't!" fretted Teresa. "She's not a Child of Mary! She oughtn't to want to tag that way. Now all the other girls' sisters will tag!"

"They haven't got sisters!" said Alanna, red-cheeked of a sudden.

"Why, Mary Alanna Costello, they have too! Jean has, and Stella has, and Grace has her little cousins!" protested Teresa, triumphantly.

"Never mind, baby," said Mrs. Costello, hurriedly. "Mother'll find you something to do. There now! How'd you like to have a raffle book on something,--a chair or a piller? And you could get all the names yourself, and keep the money in a little bag--"

"Oh, my! I wish I could!" said Jim, artfully. "Think of the last night, when the drawing comes! You'll have the fun of looking up the winning number in your book, and calling it out, in the hall."

"Would I, Dad?" said Alanna, softly, but with dawning interest.

"And then, from the pulpit, when the returns are all in," contributed Dan, warmly, "Father Crowley will read out your name,-- With Mrs. Frank Costello's booth--raffle of sofa cushion, by Miss Alanna Costello, twenty-six dollars and thirty-five cents!"

"Oo--would he, Dad?" said Alanna, won to smiles and dimples by this charming prospect.

"Of course he would!" said her father. "Now go back to your seat, Machree, and eat your dinner. When Mommer takes you and Tess to the matinee to-morrow, ask her to bring you in to me first, and you and I'll step over to Paul's, and pick out a table or a couch, or something. Eh, Mommie?"

"And what do you say?" said that lady to Alanna, as the radiant little girl went back to her chair.

Whereupon Alanna breathed a bashful "Thank you, Dad," into the ruffled yoke of her frock, and the matter was settled.

The next day she trotted beside her father to Paul's big furniture store, and after long hesitation selected a little desk of shining brass and dull oak.

"Now," said her father, when they were back in his office, and Teresa and Mrs. Costello were eager for the matinee, "here's your book of numbers, Alanna. And here, I'll tie a pencil and a string to it. Don't lose it. I've given you two hundred numbers at a quarter each, and mind the minute any one pays for one, you put their name down on the same line!"

"Oo,--oo!" said Alanna in pride. "Two hundred! That's lots of money, isn't it, Dad? That's eleven or fourteen dollars, isn't it, Dad?"

"That's fifty dollars, goose!" said her father making a dot with the pencil on the tip of her upturned little nose.

"Oo!" said Teresa, awed. Hatted, furred, and muffed, she leaned on her father's shoulder.

"Oo--Dad!" whispered Alanna, with scarlet cheeks.

"So now!" said her mother, with a little nod of encouragement and warning. "Put it right in your muff, lovey. Don't lose it. Dan or Jim will help you count your money, and keep things straight."

"And to begin with, we'll all take a chance!" said the mayor, bringing his fat palm, full of silver, up from his pocket. "How old are you, Mommie?"

"I'm thirty-seven,--all but, as well you know, Frank!" said his wife, promptly.

"Thirty-six and thirty-seven for you, then!" He wrote her name opposite both numbers. "And here's the mayor on the same page,-- forty-four! And twelve for Tessie, and eight for this highbinder on my knee, here! And now we'll have one for little Gertie!"

Gertrude Costello was not yet three months old, her mother said.

"Well, she can have number one, anyway!" said the mayor. "You make a rejooced rate for one family, I understand, Miss Costello?"

"I don't!" chuckled Alanna, locking her thin little arms about his neck, and digging her chin into his eye. So he gave her full price, and she went off with her mother in a state of great content, between rows and rows of coffins, and cases of plumes, and handles and rosettes, and designs for monuments.

"Mrs. Church will want some chances, won't she, mother?" she said suddenly.

"Let Mrs. Church alone, darlin'," advised Mrs. Costello. "She's not a Catholic, and there's plenty to take chances without her!"

Alanna reluctantly assented; but she need not have worried. Mrs. Church voluntarily took many chances, and became very enthusiastic about the desk.

She was a pretty, clever young woman, of whom all the Costellos were very fond. She lived with a very young husband, and a very new baby, in a tiny cottage near the big Irish family, and pleased Mrs. Costello by asking her advice on all domestic matters and taking it. She made the Costello children welcome at all hours in her tiny, shining kitchen, or sunny little dining-room. She made them candy and told them stories. She was a minister's daughter, and wise in many delightful, girlish, friendly ways.

And in return Mrs. Costello did her many a kindly act, and sent her almost daily presents in the most natural manner imaginable.

But Mrs. Church made Alanna very unhappy about the raffled desk. It so chanced that it matched exactly the other furniture in Mrs. Church's rather bare little drawing-room, and this made her eager to win it. Alanna, at eight, long familiar with raffles and their ways, realized what a very small chance Mrs. Church stood of getting the desk. It distressed her very much to notice that lady's growing certainty of success.

She took chance after chance. And with every chance she warned Alanna of the dreadful results of her not winning, and Alanna, with a worried line between her eyes, protested her helplessness afresh.

"She will do it, Dad!" the little girl confided to him one evening, when she and her book and her pencil were on his knee. "And it worries me so."

"Oh, I hope she wins it," said Teresa, ardently. "She's not a Catholic, but we're praying for her. And you know people who aren't Catholics, Dad, are apt to think that our fairs are pretty--pretty money-making, you know!"

"And if only she could point to that desk," said Alanna, "and say that she won it at a Catholic fair."

"But she won't," said Teresa, suddenly cold.

"I'm praying she will," said Alanna, suddenly.

"Oh, I don't think you ought, do you, Dad?" said Teresa, gravely. "Do you think she ought, Mommie? That's just like her pouring her holy water over the kitten. You oughtn't to do those things."

"I ought to," said Alanna, in a whisper that reached only her father's ear.

"You suit me, whatever you do," said Mayor Costello; "and Mrs. Church can take her chances with the rest of us."

Mrs. Church seemed to be quite willing to do so. When at last the great day of the fair came, she was one of the first to reach the hall, in the morning, to ask Mrs. Costello how she might be of use.

"Now wait a minute, then!" said Mrs. Costello, cordially. She straightened up, as she spoke, from an inspection of a box of fancy- work. "We could only get into the hall this hour gone, my dear, and 'twas a sight, after the Native Sons' Banquet last night. It'll be a miracle if we get things in order for to-night. Father Crowley said he'd have three carpenters here this morning at nine, without fail; but not one's come yet. That's the way!"

"Oh, we'll fix things," said Mrs. Church, shaking out a dainty little apron.

Alanna came briskly up, and beamed at her. The little girl was driving about on all sorts of errands for her mother, and had come in to report.

"Mother, I went home," she said, in a breathless rush, "and told Alma four extra were coming to lunch, and here are your big scissors, and I told the boys you wanted them to go out to Uncle Dan's for greens, they took the buckboard, and I went to Keyser's for the cheese-cloth, and he had only eighteen yards of pink, but he thinks Kelley's have more, and there are the tacks, and they don't keep spool-wire, and the electrician will be here in ten minutes."

"Alanna, you're the pride of me life," said her mother, kissing her. "That's all now, dearie. Sit down and rest."

"Oh, but I'd rather go round and see things," said Alanna, and off she went.

The immense hall was filled with the noise of voices, hammers, and laughter. Groups of distracted women were forming and dissolving everywhere around chaotic masses of boards and bunting. Whenever a carpenter started for the door, or entered it, he was waylaid, bribed, and bullied by the frantic superintendents of the various booths. Messengers came and went, staggering under masses of evergreen, carrying screens, rope, suit-cases, baskets, boxes, Japanese lanterns, freezers, rugs, ladders, and tables.

Alanna found the stage fascinating. Lunch and dinner were to be served there, for the five days of the fair, and it had been set with many chairs and tables, fenced with ferns and bamboo. Alanna was charmed to arrange knives and forks, to unpack oily hams and sticky cakes, and great bowls of salad, and to store them neatly away in a green room.

The grand piano had been moved down to the floor. Now and then an audacious boy or two banged on it for the few moments that it took his mother's voice or hands to reach him. Little girls gently played The Carnival of Venice or Echoes of the Ball, with their scared eyes alert for reproof. And once two of the "big" Sodality girls came up, assured and laughing and dusty, and boldly performed one of their convent duets. Some of the tired women in the booths straightened up and clapped, and called "encore!"

Teresa was not one of these girls. Her instrument was the violin; moreover, she was busy and absorbed at the Children of Mary's booth, which by four o'clock began to blossom all over its white-draped pillars and tables with ribbons and embroidery and tissue paper, and cushions and aprons and collars, and all sorts of perfumed prettiness.

The two priests were constantly in evidence, their cassocks and hands showing unaccustomed dust.

And over all the confusion, Mrs. Costello shone supreme. Her brisk, big figure, with skirts turned back, and a blue apron still further protecting them, was everywhere at once; laughter and encouragement marked her path. She wore a paper of pins on the breast of her silk dress, she had a tack hammer thrust in her belt. In her apron pockets were string, and wire, and tacks. A big pair of scissors hung at her side, and a pencil was thrust through her smooth black hair. She advised and consulted and directed; even with the priests it was to be observed that her mild, "Well, Father, it seems to me," always won the day. She led the electricians a life of it; she became the terror of the carpenters' lives.

Where was the young lady that played the violin going to stay? Send her up to Mrs. Costello's.--Heavens! We were short a tablecloth! Oh, but Mrs. Costello had just sent Dan home for one.--How on earth could the Male Quartette from Tower Town find its way to the hall? Mrs. Costello had promised to tell Mr. C. to send a carriage for them.

She came up to the Children of Mary's booth about five o'clock.

"Well, if you girls ain't the wonders!" she said to the tired little Sodalists, in a tone of unbounded admiration and surprise. "You make me ashamed of me own booth. This is beautiful."

"Oh, do you think so, mother?" said Teresa, wistfully, clinging to her mother's arm.

"I think it's grand!" said Mrs. Costello, with conviction. There was a delighted laugh. "I'm going to bring all the ladies up to see it."

"Oh, I'm so glad!" said all the girls together, reviving visibly.

"An' the pretty things you got!" went on the cheering matron. "You'll clear eight hundred if you'll clear a cent. And now put me down for a chance or two; don't be scared, Mary Riordan; four or five! I'm goin' to bring Mr. Costeller over here to-night, and don't you let him off too easy."

Every one laughed joyously.

"Did you hear of Alanna's luck?" said Mrs. Costello. "When the Bishop got here he took her all around the hall with him, and between this one and that, every last one of her chances is gone. She couldn't keep her feet on the floor for joy. The lucky girl! They're waitin' for you, Tess, darlin', with the buckboard. Go home and lay down awhile before dinner."

"Aren't you lucky!" said Teresa, as she climbed a few minutes later into the back seat with Jim, and Dan pulled out the whip.

Alanna, swinging her legs, gave a joyful assent. She was too happy to talk, but the other three had much to say.

"Mother thinks we'll make eight hundred dollars," said Teresa.

"Gee!" said the twins together, and Dan added, "If only Mrs. Church wins that desk now."

"Who's going to do the drawing of numbers?" Jimmy wondered.

"Bishop," said Dan, "and he'll call down from the platform, 'Number twenty-six wins the desk.' And then Alanna'll look in her book, and pipe up and say, 'Daniel Ignatius Costello, the handsomest fellow in the parish, wins the desk.'"

"Twenty-six is Harry Plummer," said Alanna, seriously, looking up from her chance book, at which they all laughed.

"But take care of that book," warned Teresa, as she climbed down. "Oh, I will!" responded Alanna, fervently.

And through the next four happy days she did, and took the precaution of tying it by a stout cord to her arm.

Then on Saturday, the last afternoon, quite late, when her mother had suggested that she go home with Leo and Jack and Frank and Gertrude and the nurses, Alanna felt the cord hanging loose against her hand, and looking down, saw that the book was gone.

She was holding out her arms for her coat when this took place, and she went cold all over. But she did not move, and Minnie buttoned her in snugly, and tied the ribbons of her hat with cold, hard knuckles, without suspecting anything.

Then Alanna disappeared and Mrs. Costello sent the maids and babies on without her. It was getting dark and cold for the small Costellos.

But the hour was darker and colder for Alanna. She searched and she hoped and she prayed in vain. She stood up, after a long hands-and- knees expedition under the tables where she had been earlier, and pressed her right hand over her eyes, and said aloud in her misery, "Oh, I can't have lost it! I can't have. Oh, don't let me have lost it!"

She went here and there as if propelled by some mechanical force, a wretched, restless little figure. And when the dreadful moment came when she must give up searching, she crept in beside her mother in the carriage, and longed only for some honorable death.

When they all went back at eight o'clock, she recommenced her search feverishly, with that cruel alternation of hope and despair and weariness that every one knows. The crowds, the lights, the music, the laughter, and the noise, and the pervading odor of pop-corn were not real, when a shabby, brown little book was her whole world, and she could not find it.

"The drawing will begin," said Alanna, "and the Bishop will call out the number! And what'll I say? Every one will look at me; and how can I say I've lost it! Oh, what a baby they'll call me!"

"Father'll pay the money back," she said, in sudden relief. But the impossibility of that swiftly occurred to her, and she began hunting again with fresh terror.

"But he can't! How can he? Two hundred names; and I don't know them, or half of them."

Then she felt the tears coming, and she crept in under some benches, and cried.

She lay there a long time, listening to the curious hum and buzz above her. And at last it occurred to her to go to the Bishop, and tell this old, kind friend the truth.

But she was too late. As she got to her feet, she heard her own name called from the platform, in the Bishop's voice.

"Where's Alanna Costello? Ask her who has number eighty-three on the desk. Eighty-three wins the desk! Find little Alanna Costello!"

Alanna had no time for thought. Only one course of action occurred to her. She cleared her throat.

"Mrs. Will Church has that number, Bishop," she said.

The crowd about her gave way, and the Bishop saw her, rosy, embarrassed, and breathless.

"Ah, there you are!" said the Bishop. "Who has it?"

"Mrs. Church, your Grace," said Alanna, calmly this time.

"Well, did you ever," said Mrs. Costello to the Bishop. She had gone up to claim a mirror she had won, a mirror with a gold frame, and lilacs and roses painted lavishly on its surface.

"Gee, I bet Alanna was pleased about the desk!" said Dan in the carriage.

"Mrs. Church nearly cried," Teresa said. "But where'd Alanna go to? I couldn't find her until just a few minutes ago, and then she was so queer!"

"It's my opinion she was dead tired," said her mother. "Look how sound she's asleep! Carry her up, Frank. I'll keep her in bed in the morning."

They kept Alanna in bed for many mornings, for her secret weighed on her soul, and she failed suddenly in color, strength, and appetite. She grew weak and nervous, and one afternoon, when the Bishop came to see her, worked herself into such a frenzy that Mrs. Costello wonderingly consented to her entreaty that he should not come up.

She would not see Mrs. Church, nor go to see the desk in its new house, nor speak of the fair in any way. But she did ask her mother who swept out the hall after the fair.

"I did a good deal meself," said Mrs. Costello, dashing one hope to the ground. Alanna leaned back in her chair, sick with disappointment.

One afternoon, about a week after the fair, she was brooding over the fire. The other children were at the matinee, Mrs. Costello was out, and a violent storm was whirling about the nursery windows.

Presently, Annie, the laundress, put her frowsy head in at the door. She was a queer, warm-hearted Irish girl; her big arms were still streaming from the tub, and her apron was wet.

"Ahl alone?" said Annie, with a broad smile.

"Yes; come in, won't you, Annie?" said little Alanna.

"I cahn't. I'm at the toobs," said Annie, coming in, nevertheless. "I was doin' all the tableclot's and napkins, an' out drops your little buke!"

"My--what did you say?" said Alanna, very white.

"Your little buke," said Annie. She laid the chance book on the table, and proceeded to mend the fire.

Alanna sank back in her chair. She twisted her fingers together, and tried to think of an appropriate prayer.

"Thank you, Annie," she said weakly, when the laundress went out. Then she sprang for the book. It slipped twice from her cold little fingers before she could open it.

"Eighty-three!" she said hoarsely. "Sixty--seventy--eighty-three!"

She looked and looked and looked. She shut the book and opened it again, and looked. She laid it on the table, and walked away from it, and then came back suddenly, and looked. She laughed over it, and cried over it, and thought how natural it was, and how wonderful it was, all in the space of ten blissful minutes.

And then, with returning appetite and color and peace of mind, her eyes filled with pity for the wretched little girl who had watched this same sparkling, delightful fire so drearily a few minutes ago.

Her small soul was steeped in gratitude. She crooked her arm and put her face down on it, and sank to her knees.

"New white dress, is it?" said Mrs. Costello in bland surprise. "Well, my, my, my! You'll have Dad and me in the poorhouse!"

She had been knitting a pink and white jacket for somebody's baby, but now she put it into the silk bag on her knee, dropped it on the floor, and with one generous sweep of her big arms gathered Alanna into her lap instead. Alanna was delighted to have at last attracted her mother's whole attention, after some ten minutes of unregarded whispering in her ear. She settled her thin little person with the conscious pleasure of a petted cat.

"What do you know about that, Dad?" said Mrs. Costello, absently, as she stiffened the big bow over Alanna's temple into a more erect position. "You and Tess could wear your Christmas procession dresses," she suggested to the little girl.

Teresa, apparently absorbed until this instant in what the young Costellos never called anything but the "library book," although that volume changed character and title week after week, now shut it abruptly, came around the reading-table to her mother's side, and said in a voice full of pained reminder:

"Mother! Every one will have new white dresses and blue sashes for Superior's feast!"

"I bet you Superior won't!" said Jim, frivolously, from the picture- puzzle he and Dan were reconstructing. Alanna laughed joyously, but Teresa looked shocked.

"Mother, ought he say that about Superior?" she asked.

"Jimmy, don't you be pert about the Sisters," said his mother, mildly. And suddenly the Mayor's paper was lowered, and he was looking keenly at his son over his glasses.

"What did you say, Jim?" said he. Jim was instantly smitten scarlet and dumb, but Mrs. Costello hastily explained that it was but a bit of boy's nonsense, and dismissed it by introducing the subject of the new white dresses.

"Well, well, well! There's nothing like having two girls in society!" said the Mayor, genially, winding one of Teresa's curls about his fat finger. "What's this for, now? Somebody graduating?"

"It's Mother Superior's Golden Jubilee," explained Teresa, "and there will be a reunion of 'lumnae, and plays by the girls, you know, and duets by the big girls, and needlework by the Spanish girls. And our room and Sister Claudia's is giving a new chapel window, a dollar a girl, and Sister Ligouri's room is giving the organ bench."

"And our room is giving a spear," said Alanna, uncertainly.

"A spear, darlin'?" wondered her mother. "What would you give that to Superior for?" Jim and Dan looked up expectantly, the Mayor's mouth twitched. Alanna buried her face in her mother's neck, where she whispered an explanation.

"Well, of course!" said Mrs. Costello, presently, to the company at large. Her eye held a warning that her oldest sons did not miss. "As she says, 'tis a ball all covered with islands and maps, Dad. A globe, that's the other name for it!"

"Ah, yes, a spear, to be sure!" assented the Mayor, mildly, and Alanna returned to view.

"But the best of the whole programme is the grandchildren's part," volunteered Teresa. "You know, Mother, the girls whose mothers went to Notre Dame are called the 'grandchildren.' Alanna and I are, there are twenty-two of us in all. And we are going to have a special march and a special song, and present Superior with a bouquet!"

"And maybe Teresa's going to present it and say the salutation!" exulted Alanna.

"No, Marg'ret Hammond will," Teresa corrected her quickly. "Marg'ret's three months older than me. First they were going to have me, but Marg'ret's the oldest. And she does it awfully nicely, doesn't she, Alanna? Sister Celia says it's really the most important thing of the day. And we all stand round Marg'ret while she does it. And the best of it all is, it's a surprise for Superior!"

"Not a surprise like Christmas surprises," amended Alanna, conscientiously. "Superior sort of knows we are doing something, because she hears the girls practising, and she sees us going upstairs to rehearse. But she will p'tend to be surprised."

"And it's new dresses all 'round, eh?" said her father.

"Oh, yes, we must!" said Teresa, anxiously.

"Well, I'll see about it," promised Mrs. Costello.

"Don't you want to afford the expense, mother?" Alanna whispered in her ear. Mrs. Costello was much touched.

"Don't you worry about that, lovey!" said she. The Mayor had presumably returned to his paper, but his absent eyes were fixed far beyond the printed sheet he still held tilted carefully to the light.

"Marg'ret Hammond--whose girl is that, then?" he asked presently.

"She's a girl whose mother died," supplied Alanna, cheerfully. "She's awfully smart. Sister Helen teaches her piano for nothing,-- she's a great friend of mine. She likes me, doesn't she, Tess?"

"She's three years older'n you are, Alanna," said Teresa, briskly, "and she's in our room! I don't see how you can say she's a friend of yours! Do you, mother?"

"Well," said Alanna, getting red, "she is. She gave me a rag when I cut me knee, and one day she lifted the cup down for me when Mary Deane stuck it up on a high nail, so that none of us could get drinks, and when Sister Rose said, 'Who is talking?' she said Alanna Costello wasn't 'cause she's sitting here as quiet as a mouse!'"

"All that sounds very kind and friendly to me," said Mrs. Costello, soothingly.

"I expect that's Doctor Hammond's girl?" said the Mayor.

"No, sir," said Dan. "These are the Hammonds who live over by the bridge. There's just two kids, Marg'ret and Joe, and their father. Joe served the eight o'clock Mass with me one week,--you know, Jim, the week you were sick."

"Sure," said Jim. "Hammond's a nice feller."

Their father scraped his chin with a fat hand.

"I know them," he said ruminatively. Mrs. Costello looked up.

"That's not the Hammond you had trouble with at the shop, Frank?" she said.

"Well, I'm thinking maybe it is," her husband admitted. "He's had a good deal of bad luck one way or another, since he lost his wife." He turned to Teresa. "You be as nice as you can to little Marg'ret Hammond, Tess," said he.

"I wonder who the wife was?" said Mrs. Costello. "If this little girl is a 'grandchild,' I ought to know the mother. Ask her, Tess."

Teresa hesitated.

"I don't play with her much, mother. And she's sort of shy," she began.

"I'll ask her," said Alanna, boldly. "I don't care if she is going on twelve. She goes up to the chapel every day, and I'll stop her to-morrow, and ask her! She's always friendly to me."

Mayor Costello had returned to his paper. But a few hours later, when all the children except Gertrude were settled for the night, and Gertrude, in a state of milky beatitude, was looking straight into her mother's face above her with blue eyes heavy with sleep, he enlightened his wife further concerning the Hammonds.

"He was with me at the shop," said the Mayor, "and I never was sorrier to let any man go. But it seemed like his wife's death drove him quite wild. First it was fighting with the other boys, and then drink, and then complaints here and there and everywhere, and Kelly wouldn't stand for it. I wish I'd kept him on a bit longer, myself, what with his having the two children and all. He's got a fine head on him, and a very good way with people in trouble. Kelly himself was always sending him to arrange about flowers and carriages and all. Poor lad! And then came the night he was tipsy, and got locked in the warehouse--"

"I know," said Mrs. Costello, with a pitying shake of the head, as she gently adjusted the sleeping Gertrude. "Has he had a job since, Frank?"

"He was with a piano house," said her husband, uneasily, as he went slowly on with his preparations for the night. "Two children, has he? And a boy on the altar. 'Tis hard that the children have to pay for it."

"Alanna'll find out who the wife was. She never fails me," said Mrs. Costello, turning from Gertrude's crib with sudden decision in her voice. "And I'll do something, never fear!"

Alanna did not fail. She came home the next day brimming with the importance of her fulfilled mission.

"Her mother's name was Harmonica Moore!" announced Alanna, who could be depended upon for unfailing inaccuracy in the matter of names. Teresa and the boys burst into joyous laughter, but the information was close enough for Mrs. Costello.

"Monica Moore!" she exclaimed. "Well, for pity's sake! Of course I knew her, and a sweet, dear girl she was, too. Stop laughing at Alanna, all of you, or I'll send you upstairs until Dad gets after you. Very quiet and shy she was, but the lovely singing voice! There wasn't a tune in the world she wouldn't lilt to you if you asked her. Well, the poor child, I wish I'd never lost sight of her." She pondered a moment." Is the boy still serving Mass at St. Mary's, Dan?" she said then.

"Sure," said Jim. For Dan was absorbed in the task of restoring Alanna's ruffled feelings by inserting a lighted match into his mouth.

"Well, that's good," pursued their mother. "You bring him home to breakfast after Mass any day this week, Jim. And, Tess, you must bring the little girl in after school. Tell her I knew her dear mother." Mrs. Costello's eyes, as she returned placidly to the task of labelling jars upon shining jars of marmalade, shone with their most radiant expression.

Marg'ret and Joe Hammond were constant visitors in the big Costello house after that. Their father was away, looking for work, Mrs. Costello imagined and feared, and they were living with some vague "lady across the hall." So the Mayor's wife had free rein, and she used it. When Marg'ret got one of her shapeless, leaky shoes cut in the Costello barn, she was promptly presented with shining new ones, "the way I couldn't let you get a cold and die on your father, Marg'ret, dear!" said Mrs. Costello. The twins' outgrown suits were found to fit Joe Hammond to perfection, "and a lucky thing I thought of it, Joe, before I sent them off to my sister's children in Chicago!" observed the Mayor's wife. The Mayor himself heaped his little guests' plates with the choicest of everything on the table, when the Hammonds stayed to dinner. Marg'ret frequently came home between Teresa and Alanna to lunch, and when Joe breakfasted after Mass with Danny and Jim, Mrs. Costello packed his lunch with theirs, exulting in the chance. The children became fast friends, and indeed it would have been hard to find better playfellows for the young Costellos, their mother often thought, than the clever, appreciative little Hammonds.

Meantime, the rehearsals for Mother Superior's Golden Jubilee proceeded steadily, and Marg'ret, Teresa, and Alanna could talk of nothing else. The delightful irregularity of lessons, the enchanting confusion of rehearsals, the costumes, programme, and decorations were food for endless chatter. Alanna, because Marg'ret was so genuinely fond of her, lived in the seventh heaven of bliss, trotting about with the bigger girls, joining in their plans, and running their errands. The "grandchildren" were to have a play, entitled "By Nero's Command," in which both Teresa and Marg'ret sustained prominent parts, and even Alanna was allotted one line to speak. It became an ordinary thing, in the Costello house, to hear the little girl earnestly repeating this line to herself at quiet moments, "The lions,--oh, the lions!" Teresa and Marg'ret, in their turn, frequently rehearsed a heroic dialogue which began with the stately line, uttered by Marg'ret in the person of a Roman princess: "My slave, why art thou always so happy at thy menial work?"

One day Mrs. Costello called the three girls to her sewing-room, where a brisk young woman was smoothing lengths of snowy lawn on the long table.

"These are your dresses, girls," said the matron. "Let Miss Curry get the len'ths and neck measures. And look, here's the embroidery I got. Won't that make up pretty? The waists will be all insertion, pretty near."

"Me, too?" said Marg'ret Hammond, catching a rapturous breath.

"You, too," answered Mrs. Costello in her most matter-of-fact tone. "You see, you three will be the very centre of the group, and it'll look very nice, your all being dressed the same--why, Marg'ret, dear!" she broke off suddenly. For Marg'ret, standing beside her chair, had dropped her head on Mrs. Costello's shoulder and was crying.

"I worried so about my dress," said she, shakily, wiping her eyes on the soft sleeve of Mrs. Costello's shirt-waist; when a great deal of patting, and much smothering from the arms of Teresa and Alanna had almost restored her equilibrium, "and Joe worried too! I couldn't write and bother my father. And only this morning I was thinking that I might have to write and tell Sister Rose that I couldn't be in the exhibition, after all!"

"Well, there, now, you silly girl! You see how much good worrying does," said Mrs. Costello, but her own eyes were wet.

"The worst of it was," said Marg'ret, red-cheeked, but brave, "that I didn't want any one to think my father wouldn't give it to me. For you know"--the generous little explanation tugged at Mrs. Costello's heart--"you know he would if he could!"

"Well, of course he would!" assented that lady, giving the loyal little daughter a kiss before the delightful business of fitting and measuring began. The new dresses promised to be the prettiest of their kind, and harmony and happiness reigned in the sewing-room.

But it was only a day later that Teresa and Alanna returned from school with faces filled with expressions of utter woe. Indignant, protesting, tearful, they burst forth the instant they reached their mother's sympathetic presence with the bitter tale of the day's happenings. Marg'ret Hammond's father had come home again, it appeared, and he was awfully, awfully cross with Marg'ret and Joe. They weren't to come to the Costellos' any more, or he'd whip them. And Marg'ret had been crying, and they had been crying, and Sister didn't know what was the matter, and they couldn't tell her, and the rehearsal was no fun!

While their feeling was still at its height, Dan and Jimmy came in, equally roused by their enforced estrangement from Joe Hammond. Mrs. Costello was almost as much distressed as the children, and excited and mutinous argument held the Costello dinner-table that night. The Mayor, his wife noticed, paid very close attention to the conversation, but he did not allude to it until they were alone.

"So Hammond'll take no favors from me, Mollie?"

"I suppose that's it, Frank. Perhaps he's been nursing a grudge all these weeks. But it's cruel hard on the children. From his comin' back this way, I don't doubt he's out of work, and where Marg'ret'll get her white dress from now, I don't know!"

"Well, if he don't provide it, Tess'll recite the salutation," said the Mayor, with a great air of philosophy. But a second later he added, "You couldn't have it finished up, now, and send it to the child on the chance?"

His wife shook her head despondently, and for several days went about with a little worried look in her bright eyes, and a constant dread of the news that Marg'ret Hammond had dropped out of the exhibition. Marg'ret was sad, the little girls said, and evidently missing them as they missed her, but up to the very night of the dress rehearsal she gave no sign of worry on the subject of a white dress.

Mrs. Costello had offered her immense parlors for the last rehearsal of the chief performers in the plays and tableaux, realizing that even the most obligingly blind of Mother Superiors could not appear to ignore the gathering of some fifty girls in their gala dresses in the convent hall, for this purpose. Alanna and Teresa were gloriously excited over the prospect, and flitted about the empty rooms on the evening appointed, buzzing like eager bees.

Presently a few of the nuns arrived, escorting a score of little girls, and briskly ready for an evening of serious work. Then some of the older girls, carrying their musical instruments, came in laughing. Laughter and talk began to make the big house hum, the nuns ruling the confusion, gathering girls into groups, suppressing the hilarity that would break out over and over again, and anxious to clear a corner and begin the actual work. A tall girl, leaning on the piano, scribbled a crude programme, murmuring to the alert-faced nun beside her as she wrote:

"Yes, Sister, and then the mandolins and guitars; yes, Sister, and then Mary Cudahy's recitation; yes, Sister. Is that too near Loretta's song? All right, Sister, the French play can go in between, and then Loretta. Yes, Sister."

"Of course Marg'ret'll come, Tess,--or has she come?" said Mrs. Costello, who was hastily clearing a table in the family sitting- room upstairs, because it was needed for the stage setting. Teresa, who had just joined her mother, was breathless.

"Mother! Something awful has happened!"

Mrs. Costello carefully transferred to the book-case the lamp she had just lifted, dusted her hands together, and turned eyes full of sympathetic interest upon her oldest daughter,--Teresa's tragedies were very apt to be of the spirit, and had not the sensational urgency that alarms from the boys or Alanna commanded.

"What is it then, darlin'?" said she.

"Oh, it's Marg'ret, mother!" Teresa clasped her hands in an ecstasy of apprehension. "Oh, mother, can't you make her take that white dress?"

Mrs. Costello sat down heavily, her kind eyes full of regret.

"What more can I do, Tess?" Then, with a grave headshake, "She's told Sister Rose she has to drop out?"

"Oh, no, mother!" Teresa said distressfully. "It's worse than that! She's here, and she's rehearsing, and what do you think she's wearing for an exhibition dress?"

"Well, how would I know, Tess, with you doing nothing but bemoaning and bewildering me?" asked her mother, with a sort of resigned despair. "Don't go round and round it, dovey; what is it at all?"

"It's a white dress," said Teresa, desperately, "and of course it's pretty, and at first I couldn't think where I'd seen it before, and I don't believe any of the other girls did. But they will! And I don't know what Sister will say! She's wearing Joe Hammond's surplice, yes, but she is, mother!--it's as long as a dress, you know, and with a blue sash, and all! It's one of the lace ones, that Mrs. Deane gave all the altar-boys a year ago, don't you remember? Don't you remember she made almost all of them too small?"

Mrs. Costello sat in stunned silence.

"I never heard the like!" said she, presently. Teresa's fears awakened anew.

"Oh, will Sister let her wear it, do you think, mother?"

"Well, I don't know, Tess." Mrs. Costello was plainly at a loss. "Whatever could have made her think of it,--the poor child! I'm afraid it'll make talk," she added after a moment's troubled silence, "and I don't know what to do! I wish," finished she, half to herself, "that I could get hold of her father for about one minute. I'd--"

"What would you do?" demanded Teresa, eagerly, in utter faith.

"Well, I couldn't do anything!" said her mother, with her wholesome laugh. "Come, Tess," she added briskly, "we'll go down. Don't worry, dear; we'll find some way out of it for Marg'ret."

She entered the parlors with her usual genial smile a few minutes later, and the flow of conversation that never failed her.

"Mary, you'd ought always to wear that Greek-lookin' dress," said Mrs. Costello, en passant. "Sister, if you don't want me in any of the dances, I'll take meself out of your way! No, indeed, the Mayor won't be annoyed by anything, girls, so go ahead with your duets, for he's taken the boys off to the Orpheum an hour ago, the way they couldn't be at their tricks upsettin' everything!" And presently she laid her hand on Marg'ret Hammond's shoulder. "Are they workin' you too hard, Marg'ret?"

Marg'ret's answer was smiling and ready, but Mrs. Costello read more truthfully the color on the little face, and the distress in the bright eyes raised to hers, and sighed as she found a big chair and settled herself contentedly to watch and listen.

Marg'ret was wearing Joe's surplice, there was no doubt of that. But, Mrs. Costello wondered, how many of the nuns and girls had noticed it? She looked shrewdly from one group to another, studying the different faces, and worried herself with the fancy that certain undertones and quick glances were commenting upon the dress. It was a relief when Marg'ret slipped out of it, and, with the other girls, assumed the Greek costume she was to wear in the play. The Mayor's wife, automatically replacing the drawing string in a cream-colored toga lavishly trimmed with gold paper-braid, welcomed the little respite from her close watching.

"By Nero's Command" was presently in full swing, and the room echoed to stately phrases and glorious sentiments, in the high-pitched clear voices of the small performers. Several minutes of these made all the more startling a normal tone, Marg'ret Hammond's everyday voice, saying sharply in a silence:

"Well, then, why don't you say it?"

There was an instant hush. And then another voice, that of a girl named Beatrice Garvey, answered sullenly and loudly:

"I will say it, if you want me to!"

The words were followed by a shocked silence. Every one turned to see the two small girls in the centre of the improvised stage, the other performers drawing back instinctively. Mrs. Costello caught her breath, and half rose from her chair. She had heard, as all the girls knew, that Beatrice did not like Marg'ret, and resented the prominence that Marg'ret had been given in the play. She guessed, with a quickening pulse, what Beatrice had said.

"What is the trouble, girls?" said Sister Rose's clear voice severely.

Marg'ret, crimson-cheeked, breathing hard, faced the room defiantly. She was a gallant and pathetic little figure in her blue draperies. The other child was plainly frightened at the result of the quarrel.

"Beatrice--?" said the nun, unyieldingly.

"She said I was a thief!" said Marg'ret, chokingly, as Beatrice did not answer.

There was a general horrified gasp, the nun's own voice when she spoke again was angry and quick.

"Beatrice, did you say that to Marg'ret?"

"I said--I said--" Beatrice was frightened, but aggrieved too. "I said I thought it was wrong to wear a surplice, that was made to wear on the altar, as an exhibition dress, and Marg'ret said, 'Why?' and I said because I thought it was--something I wouldn't say, and Marg'ret said, did I mean stealing, and I said, well, yes, I did, and then Marg'ret said right out, 'Well, if you think I'm a thief, why don't you say so?'"

Nobody stirred. The case had reached the open court, and no little girl present could have given a verdict to save her little soul.

"But--but--" the nun was bewildered, "but whoever did wear a surplice for an exhibition dress? I never heard of such a thing!" Something in the silence was suddenly significant. She turned her gaze from the room, where it had been seeking intelligence from the other nuns and the older girls, and looked back at the stage.

Marg'ret Hammond had dropped her proud little head, and her eyes were hidden by the tangle of soft dark hair. Had Sister Rose needed further evidence, the shocked faces all about would have supplied it.

"Marg'ret," she said, "were you going to wear Joe's surplice?"

Marg'ret did not answer.

"I'm sure, Sister, I didn't mean--" stammered Beatrice. Her voice died out uncomfortably.

"Why were you going to do that, Marg'ret?" pursued the nun, quite at a loss.

Again Marg'ret did not answer.

But Alanna Costello, who had worked her way from a scandalized crowd of little girls to Marg'ret's side, and who stood now with her small face one blaze of indignation, and her small person fairly vibrating with the violence of her breathing, spoke out suddenly. Her brave little voice rang through the room.

"Well--well--" stammered Alanna, eagerly, "that's not a bad thing to do! Me and Marg'ret were both going to do it, weren't we, Marg'ret? We didn't think it would be bad to wear our own brothers' surplices, did we, Marg'ret? I was going to ask my mother if we couldn't. Joe's is too little for him, and Leo's would be just right for me, and they're white and pretty--" She hesitated a second, her loyal little hand clasping Marg'ret's tight, her eyes ranging the room bravely. She met her mother's look, and gained fresh impetus from what she saw there. "And Mother wouldn't have minded, would you, mother?" she finished triumphantly.

Every one wheeled to face Mrs. Costello, whose look, as she rose, was all indulgent.

"Well, Sister, I don't see why they shouldn't," began her comfortable voice. The tension over the room snapped at the sound of it like a cut string. "After all," she pursued, now joining the heart of the group, "a surplice is a thing you make in the house like any other dress, and you know how girls feel about the things their brothers wear, especially if they love them! Why," said Mrs. Costello, with a delightful smile that embraced the room, "there never were sisters more devoted than Marg'ret and my Alanna! However"--and now a business-like tone crept in--"however, Sister, dear, if you or Mother Superior has the slightest objection in the world, why, that's enough for us all, isn't it, girls? We'll leave it to you, Sister. You're the one to judge." In the look the two women exchanged, they reached a perfect understanding.

"I think it's very lovely," said Sister Rose, calmly, "to think of a little girl so devoted to her brother as Margaret is. I could ask Superior, of course, Mary," she added to Mrs. Costello, "but I know she would feel that whatever you decide is quite right. So that's settled, isn't it, girls?"

"Yes, Sister," said a dozen relieved voices, the speakers glad to chorus assent whether the situation in the least concerned them or not. Teresa and some of the other girls had gathered about Marg'ret, and a soothing pur of conversation surrounded them. Mrs. Costello lingered for a few satisfied moments, and then returned to her chair.

"Come now, girls, hurry!" said Sister Rose. "Take your places, and let this be a lesson to us not to judge too hastily and uncharitably. Where were we? Oh, yes, we'll go back to where Grace comes in and says to Teresa, 'Here, even in the Emperor's very palace, dost dare....' Come, Grace!"

"I knew, if we all prayed about it, your father'd let you!" exulted Teresa, the following afternoon, when Marg'ret Hammond was about to run down the wide steps of the Costello house, in the gathering dusk. The Mayor came into the entrance hall, his coat pocket bulging with papers, and his silk hat on the back of his head, to find his wife and daughters bidding the guest good-by. He was enthusiastically imformed of the happy change of event.

"Father," said Teresa, before fairly freed from his arms and his kiss, "Marg'ret's father said she could have her white dress, and Marg'ret came home with us after rehearsal, and we've been having such fun!"

"And Marg'ret's father sent you a nice message, Frank," said his wife, significantly.

"Well, that's fine. Your father and I had a good talk to-day, Marg'ret," said the Mayor, cordially. "I had to be down by the bridge, and I hunted him up. He'll tell you about it. He's going to lend me a hand at the shop, the way I won't be so busy. 'Tis an awful thing when a man loses his wife," he added soberly a moment later, as they watched the little figure run down the darkening street.

"But now we're all good friends again, aren't we, mother?" said Alanna's buoyant little voice. Her mother tipped her face up and kissed her.

"You're a good friend,--that I know, Alanna!" said she.